Karafuto, Part 2: An Environmental History of the Japanese Colonization of Sakhalin

Published:: 2024-10-01

Author:: William Favre

Topics:: [Environment] [Japan] [Colonialism - Imperialism ] [Military history]

[46] Alan Wood, Russia’s Frozen Frontier. A History of Siberia and the Russian Far East 1581–1991, p. 175 onwards.

[47] Paul E. Dunscomb, Japan's Siberian intervention, 191 8-1922 : a great disobedience against the people, p. 4.

[48] Ibid, pp. 11, 55.

[49] Irish, Hokkaido, p. 200.

[50] Myers et al., The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895-1945.

[51] Dunscomb, Japanese Siberian Intervention, p. 101.

[52] John Crump, The Anarchist Movement in Japan, Anarchist Communist Editions, 1996, Chap. 1.

[53] Seltsov, Shimotomai, A History of Japan-Russia Relations…, Brill, pp. 137-151.

[54] Foreign Economic Administration, Enemy Branch, Japanese Fishing Industry, September 1945, Library of Congress, R-28-47, p. 27.

[55] John J. Stephan, Sakhalin: a History, p. 98.

[56] Skirda, Nestor Makhno, le cosaque libertaire (1888-1934).

[57] Dunscomb, chapter 4.

[58] Alan Wood, Russia’s Frozen Frontier. A History of Siberia and the Russian Far East 1581-1991, p. 186.

2. From Northern Occupation to Integration to the Empire (1920-1937)

2.1 The Collapse of Tsarist Russia and the Siberian Intervention

This second period going from the end of World War I to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War covers more or less the period of the Interbellum on the global stage and laid the ground for the general mobilization of the entire empire. The period was marked by a tumultuous political context, replacing the island to a central position from its original peripheral posture. This change of fate was explained by the turmoil of World War I and the Russian Civil War in its wake. The security of Japan’s border at the North was at stake with the collapse of the Tsarist Empire and the void left on the North half of the island, beyond the 50th parallel[46]. It augured a difficult period for the Japanese economy as well, facing a succession of booms and busts, mostly as rippling effects of the global economy on the archipelago. It was for Japan a period of profound changes on the political level, shifting from an oligarchy to a more democratic form known as the Taishō Democracy (Taishō Demokarushii undō) and fading progressively to a militaristic regime with the advent of the Shōwa era[47]. 1918 was marked a period of social upheaval, the Rice Riots (Kome kōdō), sparked by the high price of the rice and its shortage on the markets[48]. The riots compelled the Prime Minister of the time, Terauchi Masatake, to resign due to his gestion of the crisis, deemed brutal by the civil society. With the advent of the Taishō era, we see that Japanese society grew towards a polity equipped with stronger control institutions of political power. For short, the balance of power on the home islands became slightly more balanced.

Nevertheless, the Japanese Empire, while looking more egalitarian, kept blatant inequalities among its colonies between the Japanese and the non-ethnic Japanese, even though indigenous population assimilated as Japanese identity papers as a consequence of the claimed racial proximity between the Japanese people and the ones around its control[49]. Without proper political independence and unable to express fully their cultural heritage, the colonized populations were second-class citizens in the imperium. The situation was bound to ignite with the proper spark, represented by the Wilsonian Proposition in fourteen points, among which the people of the globe shall have the right to benefit from their own sovereignty. The movement of May Fourth 1919 organized by students of Shanghai generated a wind of insurrection in the whole empire. Observing that the repressive policy didn’t function and reached its limits, the central government, with the collaboration of the colonial governments, adopted a more subtle policy. The bottom line was an integrative attitude, which was in fact a series of concessions made to convince the population to adhere to the Japanese colonial ideology[50].

Indeed, the combination of a bad conjecture, obvious inequalities and a lack of economic development formed a fertile ground for the spread of socialist and communist ideas, which was perceived as an existential threat to the central government. The situation was even worsened by the rise of communism following the collapse of the Russian empire and the recently outbroken Russian Civil War. The central government feared that the main nationalist narrative centered around the figure of the emperor could be toppled by the internationalist worker narrative and eventually overthrow the chrysanthemum throne[51]. In this regard, the fear of a revolutionary social movement wasn’t new since a first attempt to assassinate the emperor had been exposed in 1910 by the Japanese anarchist journalist Kanno Sugako (1881-1911) and others[52]. Furthermore, the Taishō era saw an increase in the urban population, mainly workers who encountered the same problems as their Western counterparts at the same period.

The Russo-Japanese relations, who recovered significantly from the detrimental Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, suffered once more greatly from the subsequent operations led by the Japanese forces during the Russian Civil War (1917-23)[53]. The Japanese Siberian Intervention of 1918 would mark a new period of instability and mistrust between Russia and Japan, suspecting each other to invade the other or to impede their respective interests in the regions disputed by both powers: Northeast China and the waters bordering the Russian Far East. In the end, the mutual distrust eventually culminated by the declaration of war by the USSR after the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on the northern positions of the Japanese empire. During this unstable period, the island of Sakhalin would bear a renewed strategic importance because of its disputed location at the heart of the Sea of Okhotsk and by its proximity with both China and Russia’s most important towns in the area (e.g. Vladivostok or Khabarovsk). Beyond its vital location, Karafuto’s coasts were surrounded by waters rich in marine resources and in fossil fuels, such the oil deposits in Northern Sakhalin[54].

In virtue of all these qualities, the Siberian Intervention operated on two fronts; one in the Maritime Provinces of Russia and on Sakhalin up to Kamchatka. In this regard, Sakhalin operated as a pivot and a naval base to launch military operation on the mainland by the intermediary of the Amur River, whose mouth was situated in front the port of Aleksandrovsk[55]. This larger military operation from 1918 to 1925 had to be understood in the larger context of the White Forces Intervention to stop the advance of the Soviet troops throughout the former Tsarist Empire. As soon as World War I ended in November 1918 and after the Bolshevik Coup of October 1917, the Tsarist Empire collapsed and ended the central authority in the empire, creating a multitude of independent local short-lived republics, within which several powers competed. We can cite for example the Ukraine, that became for a time an independent anarchist state led by Makhnovtchina movement[56]. Atop the national axis of crisis, the main axis was the political struggle between the communist forces and the “White” Forces, namely the alliance of powers who sought to whip out the Marxist regime from existence. The alliance comprised the British Empire, United States, France, Japan and the Republic of China, sharing each part of the onslaught on the fallen empire. While the British invaded from the south from the Azov Sea, the French advanced through the north from the Baltic Sea. The Japanese, the Chinese and a part of the American army marched northbound to Eastern Siberia to cut out the communist state from its access to the Pacific Oceans, rich in resources[57]. The main objective of the Japanese army, as planned by the government was to create a buffer state in the Maritime Provinces to secure its sphere of influence in mainland Asia, especially China, Manchuria and the surrounding area[58].

[59] Stephan, The Kuril Islands.

[60] Penelope Francks, Rural Economic Development in Japan, Part III, Introduction.

[61] Stephen Kotkin, David Wolff, Rediscovering Siberia, p. 92.

[62] Viktoria Antonenko, “Between Prestige and Pragmatism: Soviet Customs Relations with Japanese Concessions in Sakhalin in the1920s‒1930s”, in: Hoppō Bunka Kenkyū, pp. 4-5.

[63] Morris-Suzuki, On the Frontiers of History.

[64] Dunscombe, op. cit., pp. 220-21.

[65] Ravina and Oxford University Press, To Stand with the Nations of the World, pp. 521-2.

[66] Myers et al., The Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895-1945.

[67] Coll., Rediscovering Russia in Asia. Siberia and the Russian Far East Siberia and the Russian Far East, M.E. Sharp, New York, 1995, p.60.

[68] Idem.

[69] Joseph J. Stephen, op. cit., p. 100.

[70] Ibid., p. 125.

[71] Ibid., p. 126.

2.2 The Invasion of Northern Sakhalin

The invasion of northern Sakhalin by the Seventh Unit, based in Hokkaidō and the army of Karafuto, was quick and met scarce resistance[59]. Once the invasion was accomplished, the situation remained blocked until 1925 and the eventual signature of a second peace treaty between Japan and the new Soviet State, recognized as legitimate, the Red Army won the civil war. The reasons behind the strategic loss of the White Forces were numerous: the extreme size of the operation ground, combined with the lack of coordination between the different national armies and the logistic constraints of the White army could explain its defeat. In the case of Japan, the empire was suffering from the economic downturn of the armistice and from its inner pressures[60]. Over the course of 4 years, the Siberian Intervention will maintain control over the major cities and axes of the Pacific Coast, officially to protect the Russians from anarchy and the danger of socialist subversion[61]. For North Sakhalin, the situation would prolong three more years until the signing of peace with the USSR. In fact, the half north of the 50th parallel was invaded in retaliation to the Nikolayevsk incident of 1920 (Nikō Jiken), during which the garrison and the civilian Japanese population of Nikolayevsk on Amur were killed by an ally of the Red Army, Yakov Tryapitsyn (1897-1920) as a retaliation for a previous massacre of Russian citizens. The incident was a convenient excuse to occupy the northern half and its natural resources, such as the Russo-Japanese oil lease, temporarily under Japanese management until October 1925[62]. The invasion of the Russian Far East was almost concluded by the fall of Vladivostok and the end of the Provisional Priamur Government in October 1922. The delay of three years between the withdrawal of Japanese troops from the Russian mainland and their ultimate removal from Sakhalin could be explained by the reluctance of the Japanese military to recognize the existence of a new central power in Russia, plus abandoning the dream to create a buffer state in Yakutia would hinder their own interests in the continent[63].

Domestically, the Siberian Intervention (Shiberia Shuppei) was considered, as Dunscomb would underline in his book, as a unilateral intervention from the military without the approval of most of the population. As the conflict unfolded, the dissonance between the general population and the government or its most militaristic elements such as the genrō “senior councilors” Katō Tomosaburō (1861-1923) grew larger. The Siberian Intervention represented a good example of the inner struggles of Japanese society during the Taishō era, where two models of the political functioning of the State fought. On one side was the oligarchic model promoted by the core group of the Satsuma-Chōshu clique (Sacchō ippa) taking the most critical decisions in the name of Empire; on the other hand was a more liberal view where the political power was put in the hand of the people through a plurality of political parties[64]. For the general public and the press, the mobilization of the military represented a great display of power for nothing much, while the country was suffering domestically of many social problems related to labor and to the other colonies. Moreover, a similar opposition in opinion existed on the colonial and foreign policy of the Empire. The struggle didn’t put into question the legitimacy of an empire but the shape it should take[65]. For most of the military administrators, the interventionist method through armed conquest was considered the most adapted approach in the international context, with a strong flavor of social Darwinism[66]. An emerging, more moderate point of view derived from the Wilsonian doctrine through multilateralism. There, a more pacifistic and collaborative approach would prevail between sovereign nations.

For the island of Karafuto, the influence of the Siberian Intervention on both halves would differ slightly. The south would benefit by serving as a base for the troops to be sent on the continent from the nearby ports and by the intensification of the maritime traffic on the sea of Okhotsk, notably between the ports of Wakkanai and Ōdomari. Despite the economic crisis, the production would be supported locally by the military demand for the different supplies such as processed food for the troops or raw materials for the military material. The military presence and a progressive augmentation of immigration in the years after the war sustained the primary and secondary industries for a brief moment. The northern half of Sakhalin, experiencing a different trajectory with prolonged Russian management, lived through Japanese occupation and wasn’t damaged as badly as the rest of the Russian Far East. The environmental impact of the Japanese occupation is not well known because of the relative lack of documentation on the matter. One hypothesis would be that the logical extension to this territory of the same logic in vigor in the south: an extraction policy dedicated to the export market in direction of the metropolis or to feed the army machine for the last years of the civil war.

The occupation of North Sakhalin, beyond its strong economic implications for oil and coal, aimed to contain the presence of communism at the gates of the Japanese realm. Hara Teruyuki gives us a good chronology of the operations: “A group of [communist] partisans crossed the Tatar strait and landed at Aleksandrovsk. In mid-March 1920, they proclaimed the liquidation of the Aleksandrovsk coalition revkom, dominated by Bolsheviks, and the formation of a soviet executive committee to rule Sakhalin Island. The Japanese government dispatched a relief force. On 18-19 April, two thousand troops left Otaru for Aleksandrovsk, but ostensibly because a sheet of ice “prohibited” them from landing at Nikolaevsk, they docked instead at Aleksandrovsk on 22 April”[67]. The Japanese navy explicitly debarked in the main port of North Sakhalin to keep the threat of bolshevism under check from its soil. The invasion succeeded: “With the Japanese landing, the executive committee of the soviet for Sakhalin Island collapsed. Surviving Bolshevik loyalists fled to Nikolaevsk.”[68] The military administration of the territory was akin to Karafuto and Siberia, with the deployment of an expeditionary force from Aleksandrovsk with its official occupation beginning on August 26th, 1920, issuing a series of coercive laws for civic life. A Japanization policy was put into place, inspired from the Southern half and from the home island, with a large number of settlers coming from Japan and a boom in infrastructure construction was undertaken from the principal port of the area[69]. The planned railways and roads would stretch from Aleksandrovsk to Rykovskoe to the frontier. The process halted with the talks of the Washington Conference of 1921-22. Which resulted in the signature of the Treaty of Beijing between Japan and USSR in 1925.

When the newly established Soviet government took control of Northern Sakhalin on May 15th, 1925, they discovered an island in shambles, where forests where almost cut clean and whose mines were intentionally inundated, and the mining machinery broken[70]. The Japanese applied clearly here the scorched earth technique, trying to hamper the recovery of the territory in order to destabilize the material basis of the local Soviet government. After a period of recovery and reconstruction between 1925-8, the Far Eastern Revolutionary Committee or Dalrevkom operated in 4 administrative subdivisions or raion (Aleksandrovsk, Rykovsk, Vostochnyi and Rybnovsk). The Northern part formed first its own oblast before being attached to the Khabarovsk oblast. Under Soviet administration, the economic development of the island underwent an acceleration compared to the Tsarist era. The Komsomol or the Youth Organization of the Soviet Union was mobilized to boost the labor needed for the development plans requiring far more than the 5'000 inhabitants of the Soviet part. The Komsomol youth brigades did more or less what soldiers-farmers did for Karafuto by building roads and housing with the cleared forests. Beforehand, a group of scientists were sent from the capital to survey the resources of the island and their location[71]. Although the social manifestation of the Soviet infrastructure development looked similar, one could note a number of differences since both systems functioned on different economic systems. The main dissimilarity with the Japanese case lay in the organization of labor and the scale where most of the decisions were taken. Indeed, labor was organized in most cases in cooperatives or trade unions and collective forms of workforce management organized directly by the State since both were fused together. The decisions were mostly taken at the highest level by the central planning organ before its application’s responsibility fell on Dalrevkom and on the oblast government. Nevertheless, local authorities had a certain margin in the direction that needed to be taken for things on the ground. Needless to say, the Northern part of Sakhalin’s ecology was durably impacted, but it is however hard to know in detail which sectors were.

The invasion of northern Sakhalin by the Seventh Unit, based in Hokkaidō and the army of Karafuto, was quick and met scarce resistance[59]. Once the invasion was accomplished, the situation remained blocked until 1925 and the eventual signature of a second peace treaty between Japan and the new Soviet State, recognized as legitimate, the Red Army won the civil war. The reasons behind the strategic loss of the White Forces were numerous: the extreme size of the operation ground, combined with the lack of coordination between the different national armies and the logistic constraints of the White army could explain its defeat. In the case of Japan, the empire was suffering from the economic downturn of the armistice and from its inner pressures[60]. Over the course of 4 years, the Siberian Intervention will maintain control over the major cities and axes of the Pacific Coast, officially to protect the Russians from anarchy and the danger of socialist subversion[61]. For North Sakhalin, the situation would prolong three more years until the signing of peace with the USSR. In fact, the half north of the 50th parallel was invaded in retaliation to the Nikolayevsk incident of 1920 (Nikō Jiken), during which the garrison and the civilian Japanese population of Nikolayevsk on Amur were killed by an ally of the Red Army, Yakov Tryapitsyn (1897-1920) as a retaliation for a previous massacre of Russian citizens. The incident was a convenient excuse to occupy the northern half and its natural resources, such as the Russo-Japanese oil lease, temporarily under Japanese management until October 1925[62]. The invasion of the Russian Far East was almost concluded by the fall of Vladivostok and the end of the Provisional Priamur Government in October 1922. The delay of three years between the withdrawal of Japanese troops from the Russian mainland and their ultimate removal from Sakhalin could be explained by the reluctance of the Japanese military to recognize the existence of a new central power in Russia, plus abandoning the dream to create a buffer state in Yakutia would hinder their own interests in the continent[63].

Domestically, the Siberian Intervention (Shiberia Shuppei) was considered, as Dunscomb would underline in his book, as a unilateral intervention from the military without the approval of most of the population. As the conflict unfolded, the dissonance between the general population and the government or its most militaristic elements such as the genrō “senior councilors” Katō Tomosaburō (1861-1923) grew larger. The Siberian Intervention represented a good example of the inner struggles of Japanese society during the Taishō era, where two models of the political functioning of the State fought. On one side was the oligarchic model promoted by the core group of the Satsuma-Chōshu clique (Sacchō ippa) taking the most critical decisions in the name of Empire; on the other hand was a more liberal view where the political power was put in the hand of the people through a plurality of political parties[64]. For the general public and the press, the mobilization of the military represented a great display of power for nothing much, while the country was suffering domestically of many social problems related to labor and to the other colonies. Moreover, a similar opposition in opinion existed on the colonial and foreign policy of the Empire. The struggle didn’t put into question the legitimacy of an empire but the shape it should take[65]. For most of the military administrators, the interventionist method through armed conquest was considered the most adapted approach in the international context, with a strong flavor of social Darwinism[66]. An emerging, more moderate point of view derived from the Wilsonian doctrine through multilateralism. There, a more pacifistic and collaborative approach would prevail between sovereign nations.

For the island of Karafuto, the influence of the Siberian Intervention on both halves would differ slightly. The south would benefit by serving as a base for the troops to be sent on the continent from the nearby ports and by the intensification of the maritime traffic on the sea of Okhotsk, notably between the ports of Wakkanai and Ōdomari. Despite the economic crisis, the production would be supported locally by the military demand for the different supplies such as processed food for the troops or raw materials for the military material. The military presence and a progressive augmentation of immigration in the years after the war sustained the primary and secondary industries for a brief moment. The northern half of Sakhalin, experiencing a different trajectory with prolonged Russian management, lived through Japanese occupation and wasn’t damaged as badly as the rest of the Russian Far East. The environmental impact of the Japanese occupation is not well known because of the relative lack of documentation on the matter. One hypothesis would be that the logical extension to this territory of the same logic in vigor in the south: an extraction policy dedicated to the export market in direction of the metropolis or to feed the army machine for the last years of the civil war.

The occupation of North Sakhalin, beyond its strong economic implications for oil and coal, aimed to contain the presence of communism at the gates of the Japanese realm. Hara Teruyuki gives us a good chronology of the operations: “A group of [communist] partisans crossed the Tatar strait and landed at Aleksandrovsk. In mid-March 1920, they proclaimed the liquidation of the Aleksandrovsk coalition revkom, dominated by Bolsheviks, and the formation of a soviet executive committee to rule Sakhalin Island. The Japanese government dispatched a relief force. On 18-19 April, two thousand troops left Otaru for Aleksandrovsk, but ostensibly because a sheet of ice “prohibited” them from landing at Nikolaevsk, they docked instead at Aleksandrovsk on 22 April”[67]. The Japanese navy explicitly debarked in the main port of North Sakhalin to keep the threat of bolshevism under check from its soil. The invasion succeeded: “With the Japanese landing, the executive committee of the soviet for Sakhalin Island collapsed. Surviving Bolshevik loyalists fled to Nikolaevsk.”[68] The military administration of the territory was akin to Karafuto and Siberia, with the deployment of an expeditionary force from Aleksandrovsk with its official occupation beginning on August 26th, 1920, issuing a series of coercive laws for civic life. A Japanization policy was put into place, inspired from the Southern half and from the home island, with a large number of settlers coming from Japan and a boom in infrastructure construction was undertaken from the principal port of the area[69]. The planned railways and roads would stretch from Aleksandrovsk to Rykovskoe to the frontier. The process halted with the talks of the Washington Conference of 1921-22. Which resulted in the signature of the Treaty of Beijing between Japan and USSR in 1925.

When the newly established Soviet government took control of Northern Sakhalin on May 15th, 1925, they discovered an island in shambles, where forests where almost cut clean and whose mines were intentionally inundated, and the mining machinery broken[70]. The Japanese applied clearly here the scorched earth technique, trying to hamper the recovery of the territory in order to destabilize the material basis of the local Soviet government. After a period of recovery and reconstruction between 1925-8, the Far Eastern Revolutionary Committee or Dalrevkom operated in 4 administrative subdivisions or raion (Aleksandrovsk, Rykovsk, Vostochnyi and Rybnovsk). The Northern part formed first its own oblast before being attached to the Khabarovsk oblast. Under Soviet administration, the economic development of the island underwent an acceleration compared to the Tsarist era. The Komsomol or the Youth Organization of the Soviet Union was mobilized to boost the labor needed for the development plans requiring far more than the 5'000 inhabitants of the Soviet part. The Komsomol youth brigades did more or less what soldiers-farmers did for Karafuto by building roads and housing with the cleared forests. Beforehand, a group of scientists were sent from the capital to survey the resources of the island and their location[71]. Although the social manifestation of the Soviet infrastructure development looked similar, one could note a number of differences since both systems functioned on different economic systems. The main dissimilarity with the Japanese case lay in the organization of labor and the scale where most of the decisions were taken. Indeed, labor was organized in most cases in cooperatives or trade unions and collective forms of workforce management organized directly by the State since both were fused together. The decisions were mostly taken at the highest level by the central planning organ before its application’s responsibility fell on Dalrevkom and on the oblast government. Nevertheless, local authorities had a certain margin in the direction that needed to be taken for things on the ground. Needless to say, the Northern part of Sakhalin’s ecology was durably impacted, but it is however hard to know in detail which sectors were.

[72] Josephson and Dronin, An Environmental History of Russia, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2013, pp. 60-66.

[73] Amano, op. cit., p. 16.

[74] Mason, Dominant Narratives of Colonial Hokkaido and Imperial Japan, p. 33.

[75] Irvings, Colonial and Migratory Labour in Karafuto 1905-1941 (Doctoral Thesis), London School of Economics, London, 29/08/2014, p. 198.

[76] Idem.

[77] Ibid., p. 263.

[78] Karafuto governorate, The Karafuto Governorate’s Establishment 30th anniversary (Karafuto-chō bōsei sanjū-nen shi), 1936, Karafuto Agency, Toyohara, p. 160.

[79] Karafuto governorate, The Karafuto Governorate’s Establishment 30th anniversary (Karafuto-chō bōsei sanjū-nen shi), 1936, Karafuto Agency, Toyohara, p. 161.

[80] Stephan, Sakhalin, pp. 110-1.

[81] Stephan, p. 112.

[82] Shiode, p. 13.

[83] Karafuto governorate, The Karafuto Governorate’s Establishment 30th anniversary (Karafuto-chō bōsei sanjū-nen shi), 1936, Karafuto Agency, Toyohara, p. 144.

2.3 The Aftermath of the Russian Civil War

Oppositely, the impact of the civil war is better known. The damages seen in the Far East was only a portion of the entirety of the devastation observed due to combat. The scale of the damages were similar to the ones seen during World War I, spread on the territory of a continent-country. The stricken areas were complementary to operation theaters, notably in the margins of the fallen Tsarist Empire from where the forces allied with the White Russian (royalists) attacked. It included the regions of the Caucasus, Karelia, the Baltic Coast, the heartland of European Russia comprising the Polish border and the Volga River. However, the White Forces never managed to attain the Soviet centers of power of Moscow and Saint-Petersburg (Petrograd until 1924, and Leningrad during 1924-1991). On the Eastern Front, the concerned areas were Yakutia, Priamoria, Transbaikalia and the bordering lands of China and Mongolia. The accumulation of starvation, land mismanagement and combat on the Western Front, plus the disastrous campaigns of World War I scarred profoundly the environment by its depletion or utter destruction. The same conclusion could be advanced for the Eastern Front, though the duration of operations was less marked by World War I, the bulk of operations focusing in Vladivostok, Yakutsk, Nikolayevsk and Chita. Based on Josephson et alii, the main reasons behind the degradations of the civil war were caused by the lack of regulation for the different resources upon which farmers, refugees and deserters relied for the survival[72].

2.4 The Rise of a Local Identity

On the local political level, the post-war years were crucial as well for Karafuto because the island of Karafuto was officially designated Outer Territory (gaichi) by the central government and fell under the supervision of the Ministry of Colonial Affairs (Takumushō). It meant then that the Prefecture of Karafuto was an unofficial colony under the administration of the Bureau of Colonial Affairs (Takumukyoku), attached to the Ministry of the Interior (Naimushō). The Bureau, created after the Russo-Japanese War, would run the external territories of Karafuto, Korea, the Kwantung leased territory and was elevated to the rank of ministry in 1929[73]. Its aim consisted in the coordination of the efforts and the administration of the different colonies mainly for the purpose to populate the newly settled areas. The last years of the Bureau of Colonial Affairs saw an effort to centralize the local gestion of the colonial territories, in collaboration with the local agencies, Karafuto-chō in our case. The intended effect was to reinforce the economic and political bond between the home islands and the colonies while engaging in a more subtle gestion with a greater local autonomy for the settler’s communities.

During the 1920’s emerged a local Karafuto identity, rimming with a consistent flow of new settlers and its eventual perpetuation with the birth of the first generation of natives to Karafuto, allowing whole families to take root on the soil of Karafuto. The generation of Karafuto people (Karafuto-jin) was accelerated by the aid of the agency itself, setting socio-economic standards to make the prefecture attractive for perennial settlers. As in the case of Hokkaidō, the core of settlers was made up of militia-farmers or impoverished workers who sought a second chance on the fringes of the realm[74]. The workers in Karafuto didn’t stay rarely more than one season and moved from one contract to another before coming home after attaining a certain budget (dekasegi or “earning journey”)[75]. The infrastructures became here a tentative for settling a floating population, seen as problematic by the government[76]. The construction of schools, hospitals, housing and manufactures could be seen as an alteration of space for the purpose of living conditions’ elevation. Undeniably, infrastructures alone wouldn’t suffice, and other measures like higher salaries (mentioned above) and the quality of the work environment. Workers themselves appeared, as they migrated throughout the archipelago, to be vectors of immigration by retelling their experience to their circles or relatives, encouraging others to join as well[77]. The constant shortage of labor on the island created a void that made workers a very valuable resource.

A second measure taken in 1922 by the Karafuto agency abolished the former four sub-prefectures system to shift to a unique prefecture system divided in counties, covering the former subprefectures[78]. Later in 1929, the neighboring municipalities surrounding the city of Toyohara merged to form Toyohara county, the conurbation forming its own administrative infrastructure. Such administrative restructuration intended to centralize the development efforts in one place, reducing the numbers of interlocutors the central government had to deal with during legislation implementation. However, these were restored in 1924 due to what we might assume as a failed attempt to centralize. The emerging prefectural identities might have feared losing some of their autonomy. Sadly, the documentation didn't tell much about such backlash. With the law n°47 from 1922 concerning the “case of the regional organization of Karafuto” (Karafuto no chihōseido ni kan suru ken), the municipal council gained more autonomy regarding the election of mayors and the gestion of the subprefecture[79].

The new gain in autonomy of the regional authority in Karafuto changed mostly the political balance between the forces at work in the attribution for budget to infrastructures. The necessary amounts were broken between the Bureau of colonial affairs and regional governments, industrial corporations, major banks and the armed forces[80]. Nevertheless, it is undeniable that the power of the Karafuto agency grew significantly during that period until attaining a height in 1930 before plummeting because of the Wall Street Crash and its ripples. The dramatic augmentation of the budget (chart below) originated as the payoff of the initial investments made by the first developers of the island, the Navy, the Army and the Meiji State. Once the colony acquired sufficient benefits to become solvable, the central government began “f[a]ll steadily until by 1936 the colony received no government subsidies”[81]. The first gains acquired from the basic infrastructures led to a surplus reported to the original invested capital, which could be in turn reinjected to infrastructures. Private industrial capital came at the dawn of the Taishō era once enough capital could be gathered by the government and by the private investors. With the reduction of Tokyo’s capitals, the financial discussion boiled down to a tripartite conversation between public actors, private investors and the civil society until the central government subsided again the colony in 1941[82].

Oppositely, the impact of the civil war is better known. The damages seen in the Far East was only a portion of the entirety of the devastation observed due to combat. The scale of the damages were similar to the ones seen during World War I, spread on the territory of a continent-country. The stricken areas were complementary to operation theaters, notably in the margins of the fallen Tsarist Empire from where the forces allied with the White Russian (royalists) attacked. It included the regions of the Caucasus, Karelia, the Baltic Coast, the heartland of European Russia comprising the Polish border and the Volga River. However, the White Forces never managed to attain the Soviet centers of power of Moscow and Saint-Petersburg (Petrograd until 1924, and Leningrad during 1924-1991). On the Eastern Front, the concerned areas were Yakutia, Priamoria, Transbaikalia and the bordering lands of China and Mongolia. The accumulation of starvation, land mismanagement and combat on the Western Front, plus the disastrous campaigns of World War I scarred profoundly the environment by its depletion or utter destruction. The same conclusion could be advanced for the Eastern Front, though the duration of operations was less marked by World War I, the bulk of operations focusing in Vladivostok, Yakutsk, Nikolayevsk and Chita. Based on Josephson et alii, the main reasons behind the degradations of the civil war were caused by the lack of regulation for the different resources upon which farmers, refugees and deserters relied for the survival[72].

2.4 The Rise of a Local Identity

On the local political level, the post-war years were crucial as well for Karafuto because the island of Karafuto was officially designated Outer Territory (gaichi) by the central government and fell under the supervision of the Ministry of Colonial Affairs (Takumushō). It meant then that the Prefecture of Karafuto was an unofficial colony under the administration of the Bureau of Colonial Affairs (Takumukyoku), attached to the Ministry of the Interior (Naimushō). The Bureau, created after the Russo-Japanese War, would run the external territories of Karafuto, Korea, the Kwantung leased territory and was elevated to the rank of ministry in 1929[73]. Its aim consisted in the coordination of the efforts and the administration of the different colonies mainly for the purpose to populate the newly settled areas. The last years of the Bureau of Colonial Affairs saw an effort to centralize the local gestion of the colonial territories, in collaboration with the local agencies, Karafuto-chō in our case. The intended effect was to reinforce the economic and political bond between the home islands and the colonies while engaging in a more subtle gestion with a greater local autonomy for the settler’s communities.

During the 1920’s emerged a local Karafuto identity, rimming with a consistent flow of new settlers and its eventual perpetuation with the birth of the first generation of natives to Karafuto, allowing whole families to take root on the soil of Karafuto. The generation of Karafuto people (Karafuto-jin) was accelerated by the aid of the agency itself, setting socio-economic standards to make the prefecture attractive for perennial settlers. As in the case of Hokkaidō, the core of settlers was made up of militia-farmers or impoverished workers who sought a second chance on the fringes of the realm[74]. The workers in Karafuto didn’t stay rarely more than one season and moved from one contract to another before coming home after attaining a certain budget (dekasegi or “earning journey”)[75]. The infrastructures became here a tentative for settling a floating population, seen as problematic by the government[76]. The construction of schools, hospitals, housing and manufactures could be seen as an alteration of space for the purpose of living conditions’ elevation. Undeniably, infrastructures alone wouldn’t suffice, and other measures like higher salaries (mentioned above) and the quality of the work environment. Workers themselves appeared, as they migrated throughout the archipelago, to be vectors of immigration by retelling their experience to their circles or relatives, encouraging others to join as well[77]. The constant shortage of labor on the island created a void that made workers a very valuable resource.

A second measure taken in 1922 by the Karafuto agency abolished the former four sub-prefectures system to shift to a unique prefecture system divided in counties, covering the former subprefectures[78]. Later in 1929, the neighboring municipalities surrounding the city of Toyohara merged to form Toyohara county, the conurbation forming its own administrative infrastructure. Such administrative restructuration intended to centralize the development efforts in one place, reducing the numbers of interlocutors the central government had to deal with during legislation implementation. However, these were restored in 1924 due to what we might assume as a failed attempt to centralize. The emerging prefectural identities might have feared losing some of their autonomy. Sadly, the documentation didn't tell much about such backlash. With the law n°47 from 1922 concerning the “case of the regional organization of Karafuto” (Karafuto no chihōseido ni kan suru ken), the municipal council gained more autonomy regarding the election of mayors and the gestion of the subprefecture[79].

The new gain in autonomy of the regional authority in Karafuto changed mostly the political balance between the forces at work in the attribution for budget to infrastructures. The necessary amounts were broken between the Bureau of colonial affairs and regional governments, industrial corporations, major banks and the armed forces[80]. Nevertheless, it is undeniable that the power of the Karafuto agency grew significantly during that period until attaining a height in 1930 before plummeting because of the Wall Street Crash and its ripples. The dramatic augmentation of the budget (chart below) originated as the payoff of the initial investments made by the first developers of the island, the Navy, the Army and the Meiji State. Once the colony acquired sufficient benefits to become solvable, the central government began “f[a]ll steadily until by 1936 the colony received no government subsidies”[81]. The first gains acquired from the basic infrastructures led to a surplus reported to the original invested capital, which could be in turn reinjected to infrastructures. Private industrial capital came at the dawn of the Taishō era once enough capital could be gathered by the government and by the private investors. With the reduction of Tokyo’s capitals, the financial discussion boiled down to a tripartite conversation between public actors, private investors and the civil society until the central government subsided again the colony in 1941[82].

| 1908 | 1913 | 1917 | 1922 | 1956 | 1931 | 1935 | 1936 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profits | 1.5 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 15.5 | 21.1 | 26.4 | 40 | 28.5 |

| Expenditures | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 12.0 | 18.6 | 24.4 | 24.5 | 28.5 |

Chart 2: Chart of the Karafuto governorate’s profits and expenditures between 1908 and 1936, in million yen, with a peak in 1935[83]

.[84] Burgos, p. 3.

[85] Karafuto governorate, op. cit., p. 765.

2.5 The Completion of the Main Infrastructures

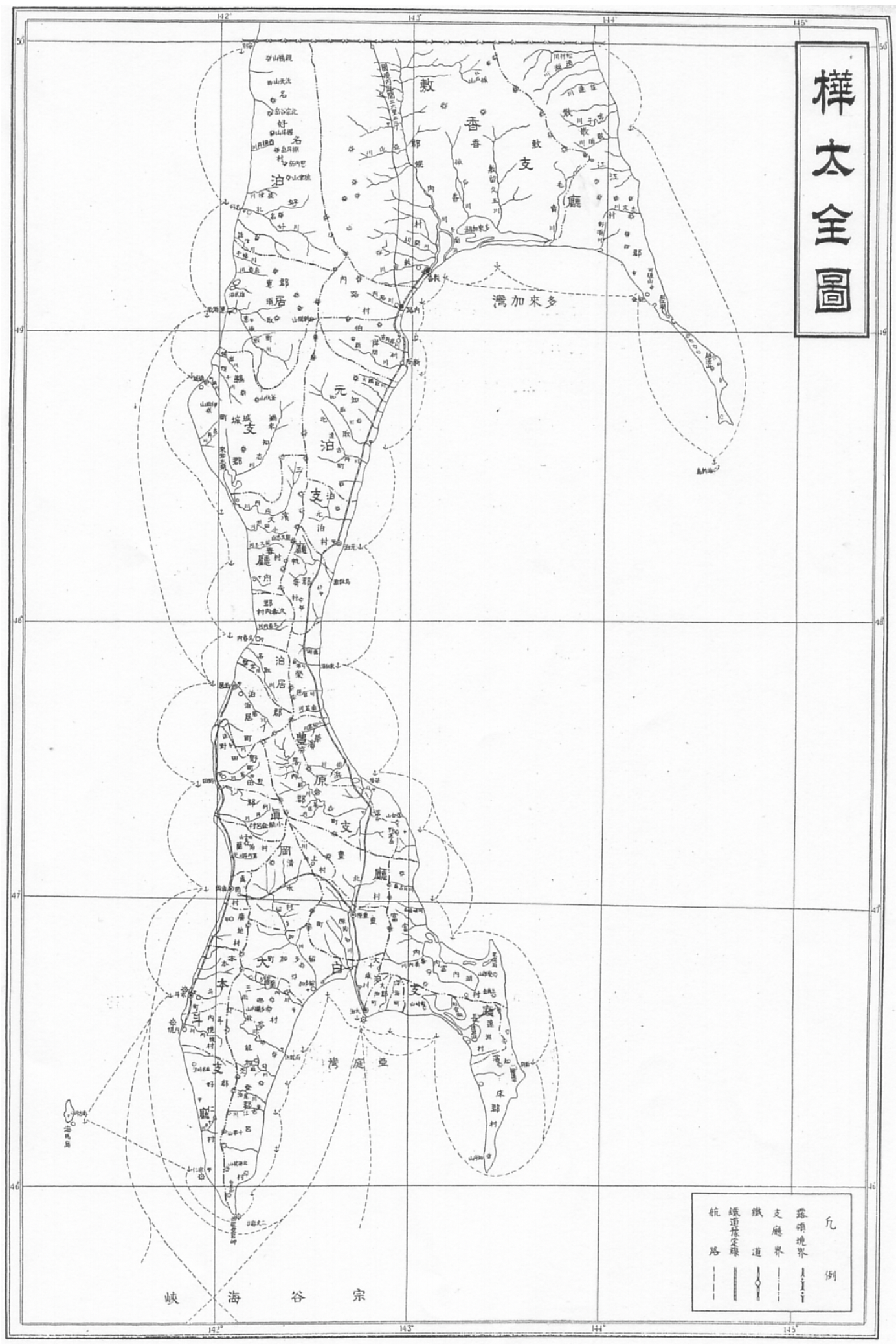

The Interbellum period rimed with a further expansion and completion of the road, railroad, telecommunication and portuary networks. Furthermore, the period saw by the turn of the 1930’s its eventual form until the Japanese defeat and its utilization in Soviet hands. From separate lines deserving one extraction hub to its transportation terminal, we could observe the interconnection of these private lines, the trunk lines and forming in the end a comprehensive railroad network used both by private and public operators (see map below). From now on, the build of the work consisted in maintenance of the created infrastructures and its subsequent extension to thinner lines. Two trunk lines ran through the island on a North-South axis on both coasts: the West coast connected Maoka to Kushunnai and the East coast trunk line Ōdomari to Koton, near the 50th parallel. A third line linked Maoka to Toyohara, the two major cities of the island. The locomotives were in their vast majority thermal, showing a better reliability during the cold temperatures of Karafuto’s winter, being equipped with special front-shovels to drive out the snow of the railways. The monopolistic operator of the area was Karafuto railways (Karafuto tetsudō kyoku), a section of the Karafuto-chō dedicated to railways and their vital role in transportation of goods throughout the island[84].

The aforementioned road networks completed the former to form a comprehensive communication net, with branches stretching out of major cities into smaller towns and hamlets that didn’t benefit from a connection to the rail network. Town such as Poronai or Esotoru could only be attained by road, where important one of the most important pulp factories were opened in 1927[85]. The roads had to be suitable for vehicles to be deployed, mostly for military purposes. We can underline here the importance of the strategic importance of an effective road network was important was the military efficiency of the island. The advantage of roads was to be less costly than railroads and to connect hence places that couldn't be reached or not profitable enough by rail. Paved roads were revealed to be useful as well for mailing and rapid troop transportation with the advent of the combustion motor and the subsequent popularization of cars for the certain sector of the population.

The Interbellum period rimed with a further expansion and completion of the road, railroad, telecommunication and portuary networks. Furthermore, the period saw by the turn of the 1930’s its eventual form until the Japanese defeat and its utilization in Soviet hands. From separate lines deserving one extraction hub to its transportation terminal, we could observe the interconnection of these private lines, the trunk lines and forming in the end a comprehensive railroad network used both by private and public operators (see map below). From now on, the build of the work consisted in maintenance of the created infrastructures and its subsequent extension to thinner lines. Two trunk lines ran through the island on a North-South axis on both coasts: the West coast connected Maoka to Kushunnai and the East coast trunk line Ōdomari to Koton, near the 50th parallel. A third line linked Maoka to Toyohara, the two major cities of the island. The locomotives were in their vast majority thermal, showing a better reliability during the cold temperatures of Karafuto’s winter, being equipped with special front-shovels to drive out the snow of the railways. The monopolistic operator of the area was Karafuto railways (Karafuto tetsudō kyoku), a section of the Karafuto-chō dedicated to railways and their vital role in transportation of goods throughout the island[84].

The aforementioned road networks completed the former to form a comprehensive communication net, with branches stretching out of major cities into smaller towns and hamlets that didn’t benefit from a connection to the rail network. Town such as Poronai or Esotoru could only be attained by road, where important one of the most important pulp factories were opened in 1927[85]. The roads had to be suitable for vehicles to be deployed, mostly for military purposes. We can underline here the importance of the strategic importance of an effective road network was important was the military efficiency of the island. The advantage of roads was to be less costly than railroads and to connect hence places that couldn't be reached or not profitable enough by rail. Paved roads were revealed to be useful as well for mailing and rapid troop transportation with the advent of the combustion motor and the subsequent popularization of cars for the certain sector of the population.

[Fig. 6]: Advertisement for the Hontō-Ōdomari-Toyohara bus line from the Southern Karafuto Railway Company (Minami Karafuto Tetsudō Kabushiki Kaisha). The slogan claims “guidance through Southern Karafuto by bus/rail. The short route between Hontō and Ōdomari-Toyohara”, Southern Karafuto Railway Company, Unknown date[86].

[86] National Diet Library Digital Collections, View source, consulted on 24.09.22.

[87] Seow, Carbon Technocracy.

[88] Walker, The Toxic Archipelago.

[89] Mosk, Japanese Industrial History, chapter 2.

[90] Seow, Carbon Technocracy, p. 175.

This surge in infrastructure reposed on two pillars, a concentration in capital and resources and a higher energetic cost to operate and maintain such an intricate system that mostly has been constructed during the 1910’s and 1920’s. As pointed out by different researches, such as Victor Seow[87] or Brett L. Walker[88], the progressive but rapid shift to fossil fuels (coal, oil and gas) multiplied by large the calorific capacity of the Japanese society as a whole, alimenting the machines that sustained the industrialization of the archipelago. The main problem was to secure a durable and an accessible supply of energy to foster the economic growth and the complexification of the emerging Meiji State. Worse, the major resource hubs located on the periphery of the archipelago whereas the industrial core in Ōsaka and Tōkyō were distant from those[89]. The coal mines situated in Japan propre were Miike (Ōita prefecture) and Mikasa; while the most valuable in overseas territory where the Kawakami (Kawakami tansan) and Fushun coal fields respectively in Sakhalin and Manchuria[90].

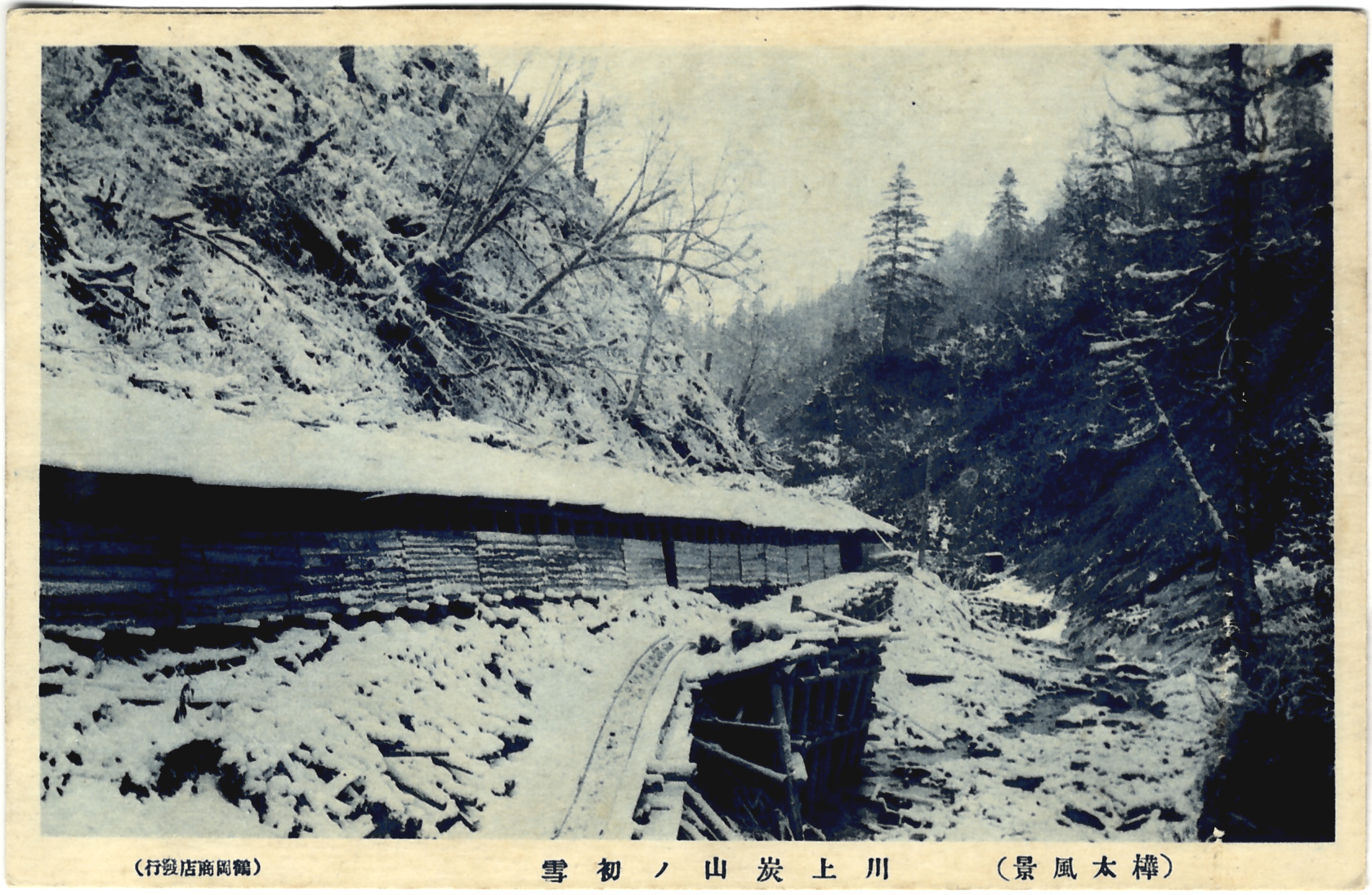

[Fig. 7]: Postcard of “Landscapes of Karafuto” (Karafuto fūkei) with the photograph of the “First Snow in Kawakami Coal Mine” (Kawakami Tanzan no Shosetsu), Author unknown, Edited by the Tsuruoka Shōten, unknown date [91].

[91] Wikipedia Commons, View source, consulted on 24.09.22.

[92] Sanada, “Research and Development History of Coke Manufacturing in Japan.”, p. 2.

[93] The second papermill opened by the Ōji paper company was in the prefecture of Shizuoka in 1889

[94] Viktoriia Antonenko, « Between Prestige and Pragmatism: Soviet Customs Relations with Japanese Concessions in Sakhalin in the 1920s–1930s”, in: Hoppō Ninbun Kenkyū (Northern Social Studies), 15, 1-21, 25.03.2022, pp. 2-3.

[95] 村上隆. and 村上隆, 1942-, 北樺太石油コンセッション1925-1944 = Kita Karafuto (Northern Sakhalin) oil concession 1925-1944, p. 144-5.

[96] Jones, Routes of Power, chapter 3.

[97] See pictures below.

[98] Walker, The Toxic Archipelago, pp. 75-77.

[99] Lu, The Making of Japanese Settler Colonialism, p. 189.

[100] Handō, Shōwa shi 1926-1945 (Histoire de l’ère Shōwa 1926-45), p. 120.

[101] Amano, « Karafuto as a Border Island of the Empire of Japan: In Comparaison with Okinawa”, in: Eurasia

Border Review, 10(1), 3-19, 2019, p.6.

[102] Nakamura Taishō, Shokuminchi Karafuto no Nōgyō Kaitaku oyobi Iminkaisha ni okeru Tokukabu Shōroku teki Nashunaru Aidentiti no kenkyū [The Agricultural Development of Colonial Karafuto and the record-based Research of National Identity in Immigration Societies], 2010, Kyoto University, chapter 6.

In order to secure the lifelines of the state and the growing empire from the Russo-Japanese war onwards, the coal fields were linked to the main industrial ports by a comprehensive rail and maritime network that would work the black blood vessels of the empire. Railways were generally the entry point for coal and would connect to the main national owned lines into the busiest and nearest deep-water ports. Once conveyed by the ship to the main industrial centers of Honshū or alimenting secondary hubs where we find processes needing a high concentration of energy. We can cite for example the steel industry of Kamaishi, in Iwate prefecture, that used partly coal from the northern boundaries of the realm[92]. Once discharged, the coal would be stocked in large deposits waiting to be burned sooner or later. For inland transportation, the opposite scheme was applied, and fret trains would transport the precious cargo load to destinations such as the Shizuoka prefecture, where paper manufacturers could be found[93].

2.6 Transborder Lifeline

In this context of energetic brittleness, the riches of Northern Sakhalin became even more interesting with the lease policy engaged by the Kremlin. The consecutive shocks of the Russian Revolution and the Civil War left the economy in shreds, necessitating urgent economic measures to restore the domestic economy. The solution proposed by Lenin and the Communist party was the pragmatic NEP for “New Economic Policy” or novaya ekonomicheskaya politika, which introduced temporally capitalistic elements in the Soviet command economy. The Soviet market was open to foreign capitals between 1921 and 1928, through the system of concessions and joined investments[94]. For the Russo-Japanese case, the oil field of North Sakhalin was particularly profitable and lasted beyond the end of the NEP itself when it was liquidated on order of Stalin in 1944. During its eighteen years of existence (1926-1944), the oil concession of North Sakhalin in Okha would succeed a previous concession given to British investors, the North Sakhalin Oil Company Ltd. Being born from the signature of the Treaty of Beijing of 1925, the company kept its name as the Kita Karafuto Sekiyu Kabushiki Kaisha and was operated by the Japanese Imperial Navy. The Okha oil field, among others, would supply the Imperial Navy until the end of the Pacific War and reached a peak production of 313’600 tons exported to Japan, for a total output of 644’855 tons for Okha alone[95].

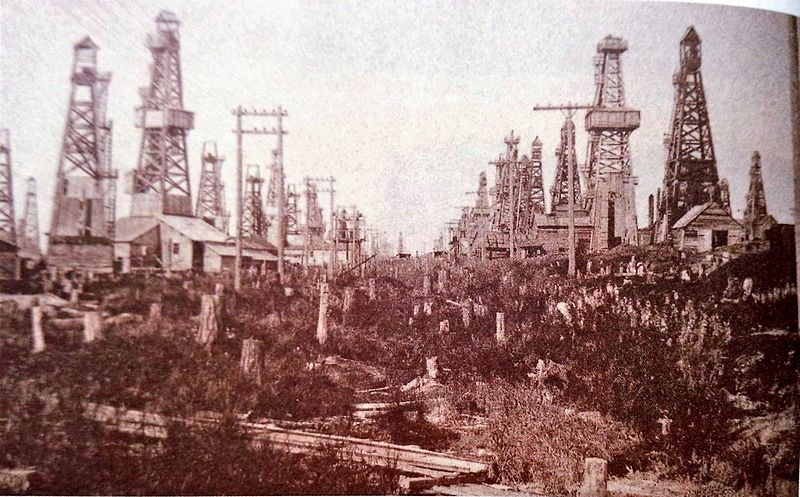

The environmental consequences are similar to what we could observe in other cases, such the oil fields of Titusville in Pennsylvania, as shown by Christopher F. Jones[96]. The once lush forests of the area had been cut clear to put into place an extraction complex where numerous pumping towers were installed to exploit the oil fields. Deforestation and pollution were the two faces of a local environmental disaster, resulting in an environmental depletion with a heavily engineered environment modified by human needs. Based on photographic materials, one could remark the trees stomps and an industrial landscape emerging with pumping stations and electrical lines[97]. The industrial complex was indeed particularly large as it was divided in three areas: the drilling area where the pits were found, the treatment and storage areas and the shipment area from where the oil left the port to mainly the home islands. It seemed that the oil was distilled on the spot, making the second area the heart of the industrial compound. The administrative buildings and the dormitories were located near the heart of the complex, to maximize the distance and the gestion of the site.

Such conclusions apply with widely differing context with other works of infrastructures throughout the island and even with other parts of the Japanese Imperium. As Brett L. Walker would illustrate in his work Toxic Archipelago that the application of rationalization or industrialization would translate often in materials terms into a simplification of a complex environment or a landscape in order to fit the needs or the perception of nature at a certain time and place[98]. These became through this process engineered or anthropized environments with various degrees depending their function and their design. In the case of infrastructures, their main purpose was to answer the multiple needs of an industrializing society that took over a territory with relatively scarce human presence; trying to excess its riches for a larger territorial ensemble. Infrastructures covered thus a wide array of tasks going from transportation to housing or extraction. The rapid pace of the Japanese establishment on the Southern Island was met with heavy infrastructures and a deep impact on the local environment.

Moreover, the effects not only of infrastructures on land but in maritime spaces should be considered as well. Karafuto wasn’t only interesting for its ground resources but mostly for its maritime resources that would be exported all throughout the Empire. The ports of Ōdomari, Hontō or Maoka became important fishing ports and served as headquarters for industrial fishing boats. With such potent tools, the influence of these infrastructure could be observed on the stocks of the most exploited fishes such as sardines or herrings. The seafloor was concerned as well with such considerations, to a more limited extent compared to the upper sea levels. Telecommunications, essential to the functioning of an industrialized society, materialized pretty concretely into submarine cables and wires, connecting Karafuto to the continent and to the home islands. The Sōya strait (Sōya kaikyō) became with the intensification of the maritime traffic and reinforced interconnection of Hokkaidō to Sakhalin a multileveled communication hub at the fringes of Japan.

2.7 Prewar Economic Hardships

The entrance to the Shōwa era was quite brutal for Japan. With the Great Depression and the rise of protectionism in many industrialized countries, the Japanese economy as a whole was deeply impacted since its main exportation outlets were severely restricted from 1931 onwards. The result for Karafuto was mixed. On one hand, Karafuto’s economy depended mainly on the interior market that plummeted and contracted with a sudden restriction to outside markets. The budgetary ripples from the metropolis could be seen on the Karafuto agency’s own budget, experiencing a slight drop during the beginning of the crisis, until the war economy in the mid-1930’s. From this period until the end of the Pacific War, the budget of the agency remained stable and didn’t go much higher.

These changes could be explained by the context of the Empire as a whole. As a response to the economic downturn, the Imperial Army and the Imperial Navy saw colonial conquest as an advantageous method to deal with the problems encountered domestically. The struggling economy connected into a feedback loop with social issues and political instability, creating a favorable context for Malthusian theories to expand[99]. Some military and ideologues, like Ishihara Kanji (1889-1949), analyzed that the facing decline if a prompt reaction wasn’t decided to create its own sphere of influence in order to oppose the other great powers of the time. In this context, the fear of socialism and conflict with USSR gave a growing audience to the military faction, who progressively took control of the government through multiple incidents[100]. The invasion of Manchuria and the creation of Manchukuo represented the perfect example of an urge to create an autarkic bloc or sphere of influence axed on Japan. Manchuria became a new market where industrialists and the domestic production found an outlet, mainly in manufactured goods in exchange for soy and coal.

Additionally, we could notice a starch turn of the economy to the military that went hand in hand with the ubiquitous place that the militarization took in Japanese society. The Imperial forces were, in parallel with their growing adventurism, one of the only political entities with expanding needs at a time of demand contraction. Although it was still too soon to qualify it as a war economy, such a shift could be seen for example with the industrialization of the newly acquired territories in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia (Manmō). We could observe a modification as well at the national level of the manufacturing industry itself from light industries to heavy industries, in order to ensure the domestic autarky for products on which the military depended. Products with high energy and capital concentration (steel, chemicals, fuel, etc…) were generated by industrial aggregate or the infamous zaibatsu such Mitsubishi or Mitsui who owned both the capital and the productive capacities.

In the case of Karafuto, its economy and the infrastructures that were tied up closely benefited much of the autarkist push, with help from the government. The competition between colonies hampered the economic prosperity of the territory, the myth of a colony able to resolve every problem of the metropolis was well now set on the continent, at the same time a shield and an Eldorado for the government and the supporters of military expansionism. Karafuto lagged behind so to say and was as Amano pointed out a “whether border islands were regarded as a part of the homeland depended on the capricious wishes of central governments. Border islands could be incorporated into the mainland at one time, but then they could be de-bordered and excluded in the future, in accordance with the governments’ wishes. This has been termed the unstable status “uneasiness of border islands”, though this situation wouldn’t fully bloom until the end of the Pacific War[101].

In 1933, the central government launched a development plan in the agriculture, mining and forestry industry, with technicians from those various fields coming from major universities such as the Imperial Universities of Kyōto or Hokkaidō. The experts split between different research stations established in different locations on the Southern half. The type of governance taken by the government differed from the initial dynamic of colonization on the island that capitalized more on economic forces and flux attract people to the colony[102]. Then, the central government adopted a more dirigiste interventionist approach, as we could see in the case of the United States or USSR under Stalin, marking the beginning of a state implication that wouldn’t stop until the end of World War II. The convergence of the State, scientists, private actors and the Army or Navy united under the flag of national exaltation and affirmation of a particularity of the Japanese people and their subjects.

2.6 Transborder Lifeline

In this context of energetic brittleness, the riches of Northern Sakhalin became even more interesting with the lease policy engaged by the Kremlin. The consecutive shocks of the Russian Revolution and the Civil War left the economy in shreds, necessitating urgent economic measures to restore the domestic economy. The solution proposed by Lenin and the Communist party was the pragmatic NEP for “New Economic Policy” or novaya ekonomicheskaya politika, which introduced temporally capitalistic elements in the Soviet command economy. The Soviet market was open to foreign capitals between 1921 and 1928, through the system of concessions and joined investments[94]. For the Russo-Japanese case, the oil field of North Sakhalin was particularly profitable and lasted beyond the end of the NEP itself when it was liquidated on order of Stalin in 1944. During its eighteen years of existence (1926-1944), the oil concession of North Sakhalin in Okha would succeed a previous concession given to British investors, the North Sakhalin Oil Company Ltd. Being born from the signature of the Treaty of Beijing of 1925, the company kept its name as the Kita Karafuto Sekiyu Kabushiki Kaisha and was operated by the Japanese Imperial Navy. The Okha oil field, among others, would supply the Imperial Navy until the end of the Pacific War and reached a peak production of 313’600 tons exported to Japan, for a total output of 644’855 tons for Okha alone[95].

The environmental consequences are similar to what we could observe in other cases, such the oil fields of Titusville in Pennsylvania, as shown by Christopher F. Jones[96]. The once lush forests of the area had been cut clear to put into place an extraction complex where numerous pumping towers were installed to exploit the oil fields. Deforestation and pollution were the two faces of a local environmental disaster, resulting in an environmental depletion with a heavily engineered environment modified by human needs. Based on photographic materials, one could remark the trees stomps and an industrial landscape emerging with pumping stations and electrical lines[97]. The industrial complex was indeed particularly large as it was divided in three areas: the drilling area where the pits were found, the treatment and storage areas and the shipment area from where the oil left the port to mainly the home islands. It seemed that the oil was distilled on the spot, making the second area the heart of the industrial compound. The administrative buildings and the dormitories were located near the heart of the complex, to maximize the distance and the gestion of the site.

Such conclusions apply with widely differing context with other works of infrastructures throughout the island and even with other parts of the Japanese Imperium. As Brett L. Walker would illustrate in his work Toxic Archipelago that the application of rationalization or industrialization would translate often in materials terms into a simplification of a complex environment or a landscape in order to fit the needs or the perception of nature at a certain time and place[98]. These became through this process engineered or anthropized environments with various degrees depending their function and their design. In the case of infrastructures, their main purpose was to answer the multiple needs of an industrializing society that took over a territory with relatively scarce human presence; trying to excess its riches for a larger territorial ensemble. Infrastructures covered thus a wide array of tasks going from transportation to housing or extraction. The rapid pace of the Japanese establishment on the Southern Island was met with heavy infrastructures and a deep impact on the local environment.

Moreover, the effects not only of infrastructures on land but in maritime spaces should be considered as well. Karafuto wasn’t only interesting for its ground resources but mostly for its maritime resources that would be exported all throughout the Empire. The ports of Ōdomari, Hontō or Maoka became important fishing ports and served as headquarters for industrial fishing boats. With such potent tools, the influence of these infrastructure could be observed on the stocks of the most exploited fishes such as sardines or herrings. The seafloor was concerned as well with such considerations, to a more limited extent compared to the upper sea levels. Telecommunications, essential to the functioning of an industrialized society, materialized pretty concretely into submarine cables and wires, connecting Karafuto to the continent and to the home islands. The Sōya strait (Sōya kaikyō) became with the intensification of the maritime traffic and reinforced interconnection of Hokkaidō to Sakhalin a multileveled communication hub at the fringes of Japan.

2.7 Prewar Economic Hardships

The entrance to the Shōwa era was quite brutal for Japan. With the Great Depression and the rise of protectionism in many industrialized countries, the Japanese economy as a whole was deeply impacted since its main exportation outlets were severely restricted from 1931 onwards. The result for Karafuto was mixed. On one hand, Karafuto’s economy depended mainly on the interior market that plummeted and contracted with a sudden restriction to outside markets. The budgetary ripples from the metropolis could be seen on the Karafuto agency’s own budget, experiencing a slight drop during the beginning of the crisis, until the war economy in the mid-1930’s. From this period until the end of the Pacific War, the budget of the agency remained stable and didn’t go much higher.

These changes could be explained by the context of the Empire as a whole. As a response to the economic downturn, the Imperial Army and the Imperial Navy saw colonial conquest as an advantageous method to deal with the problems encountered domestically. The struggling economy connected into a feedback loop with social issues and political instability, creating a favorable context for Malthusian theories to expand[99]. Some military and ideologues, like Ishihara Kanji (1889-1949), analyzed that the facing decline if a prompt reaction wasn’t decided to create its own sphere of influence in order to oppose the other great powers of the time. In this context, the fear of socialism and conflict with USSR gave a growing audience to the military faction, who progressively took control of the government through multiple incidents[100]. The invasion of Manchuria and the creation of Manchukuo represented the perfect example of an urge to create an autarkic bloc or sphere of influence axed on Japan. Manchuria became a new market where industrialists and the domestic production found an outlet, mainly in manufactured goods in exchange for soy and coal.

Additionally, we could notice a starch turn of the economy to the military that went hand in hand with the ubiquitous place that the militarization took in Japanese society. The Imperial forces were, in parallel with their growing adventurism, one of the only political entities with expanding needs at a time of demand contraction. Although it was still too soon to qualify it as a war economy, such a shift could be seen for example with the industrialization of the newly acquired territories in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia (Manmō). We could observe a modification as well at the national level of the manufacturing industry itself from light industries to heavy industries, in order to ensure the domestic autarky for products on which the military depended. Products with high energy and capital concentration (steel, chemicals, fuel, etc…) were generated by industrial aggregate or the infamous zaibatsu such Mitsubishi or Mitsui who owned both the capital and the productive capacities.

In the case of Karafuto, its economy and the infrastructures that were tied up closely benefited much of the autarkist push, with help from the government. The competition between colonies hampered the economic prosperity of the territory, the myth of a colony able to resolve every problem of the metropolis was well now set on the continent, at the same time a shield and an Eldorado for the government and the supporters of military expansionism. Karafuto lagged behind so to say and was as Amano pointed out a “whether border islands were regarded as a part of the homeland depended on the capricious wishes of central governments. Border islands could be incorporated into the mainland at one time, but then they could be de-bordered and excluded in the future, in accordance with the governments’ wishes. This has been termed the unstable status “uneasiness of border islands”, though this situation wouldn’t fully bloom until the end of the Pacific War[101].

In 1933, the central government launched a development plan in the agriculture, mining and forestry industry, with technicians from those various fields coming from major universities such as the Imperial Universities of Kyōto or Hokkaidō. The experts split between different research stations established in different locations on the Southern half. The type of governance taken by the government differed from the initial dynamic of colonization on the island that capitalized more on economic forces and flux attract people to the colony[102]. Then, the central government adopted a more dirigiste interventionist approach, as we could see in the case of the United States or USSR under Stalin, marking the beginning of a state implication that wouldn’t stop until the end of World War II. The convergence of the State, scientists, private actors and the Army or Navy united under the flag of national exaltation and affirmation of a particularity of the Japanese people and their subjects.

[Fig. 8]: General Map of Karafuto (Karafuto Senzu), format unknown, author unknown, 1930’s[103].

[103] Abasa, Wikipedia Commons, View source, consulted on 24.09.22.

[104] Stephan, Sakhalin, pp. 130-1.

[105] Karafuto governorate, op. cit., pp. 1024-6.

[106] Stephan, Sakhalin, pp. 126-7.

[107] Stephan, p. 128.

The extractive and manufacturing sectors of the sakhalinian economy benefited the most from the development plans, especially the coal and the pulp industry. At the beginning of the Shōwa era, the mines weren’t that developed yet and benefited greatly from the development planned by the government. The Kawakami coal mine and the sulfite paper industry benefited greatly from such development plans until the height of the war. Railways, roads and structures were taken and reinforcements during this period of time[104]. The government-driven infrastructure growth allowed the island to hold the ripples of the financial crisis and the progressive isolation of the archipelago on the international level. During the prewar era, we could count 9 mines beside coal mines, in which we could find metals like iron, silver and copper. These metals were all necessary for the various products found in heavy industries, but it seems that the heaviest infrastructures to refine the various types of ores were located in the home islands, notably Hokkaidō, having a denser industrial base than its northern neighbor. It is mainly a march north to the Russo-Japanese border that we could observe the opening of mines, in order to solidify the Japanese presence as tensions accumulated between the two empires; whereas the most ancient mining operations were situated in the south (Kawakami, Shiraura, Chitori, etc...)[105].

On the Soviet side under Stalin, North Sakhalin was put under the administration of the Kraï of the Far East. The area didn’t receive much attention since the Treaty of Beijing from the Kremlin since its focus was directed to the Western part of the USSR, comprising the Baltic Coast and the eastern side of the Ural Mountains in Western Siberia. There, the accelerated industrialization program in three five-year plans achieved the Soviet leader’s dream of an industrial powerhouse but at a high cost. Even if we had mentions of labor camps and gulags in Siberia, these were mostly located in Western Siberia and in its Northern part. The remoteness of the island from its center didn't make the project appealing enough to a degree similar to the development projects we saw elsewhere in the breakneck development planning of the Stalinian era. However, the island’s Soviet part wasn’t devoid of human presence but could be explained for the same reasons on the Japanese side. As tensions rose, the Soviet military presence was reinforced by the sending of whole units of the Delrevkom and a wave of migrants from different parts of the USSR to transform the borderland into a zone of garrison[106]. However, compared to the continent, the defenses of Sakhalin weren’t as pronounced and were eventually controlled by the Japanese in 1941 before the final defeat of 1945. Centered around Aleksandrovsk, the Northern part’s economy revolved mainly around the exploitation of carbon resources and in fishing or fur trade. The agricultural and breeding sector was present as well and adapted to the harsh climate of the Northern part: the production of sugar beets or fur[107].

On the Soviet side under Stalin, North Sakhalin was put under the administration of the Kraï of the Far East. The area didn’t receive much attention since the Treaty of Beijing from the Kremlin since its focus was directed to the Western part of the USSR, comprising the Baltic Coast and the eastern side of the Ural Mountains in Western Siberia. There, the accelerated industrialization program in three five-year plans achieved the Soviet leader’s dream of an industrial powerhouse but at a high cost. Even if we had mentions of labor camps and gulags in Siberia, these were mostly located in Western Siberia and in its Northern part. The remoteness of the island from its center didn't make the project appealing enough to a degree similar to the development projects we saw elsewhere in the breakneck development planning of the Stalinian era. However, the island’s Soviet part wasn’t devoid of human presence but could be explained for the same reasons on the Japanese side. As tensions rose, the Soviet military presence was reinforced by the sending of whole units of the Delrevkom and a wave of migrants from different parts of the USSR to transform the borderland into a zone of garrison[106]. However, compared to the continent, the defenses of Sakhalin weren’t as pronounced and were eventually controlled by the Japanese in 1941 before the final defeat of 1945. Centered around Aleksandrovsk, the Northern part’s economy revolved mainly around the exploitation of carbon resources and in fishing or fur trade. The agricultural and breeding sector was present as well and adapted to the harsh climate of the Northern part: the production of sugar beets or fur[107].

[Fig. 9]: Photograph of Karafuto Oil Company on the site of the Okha oil fields, taken in 1929, Unknown[108].

[108] Iso10970, Wikipedia commons, View source , consulted on 24.09.22.

[109] Antonenko, p. 16.

[110] Foreign Economic Administration, Enemy Branch, Japanese Fishing Industry, September 1945, Library of Congress, R-28-47, p. 23.

[111] Sokolsky, “Fishing for Empire.”, pp. 3-4.

As we could see, despite the tensions between the two political entities, circulations on the economic and political level occurred and benefited both sides, especially when the State needed the significant amount of currencies it needed in order to accomplish its reforms. In the well-studied case of Okha oil fields in North Sakhalin, the nationality of laborers was obviously Soviet in its great majority whereas Japanese were situated in the higher levels of the hierarchy, where technicians and white-collar administrators could be found. The Japanese cadres of the concessions had to deal with both the Soviet laborers who could come out on strike and still be backed by the local authorities[109]. The accumulation of tensions made the day to day management difficult and could spark diplomatic incidents, which could have occurred on several occasions. The rule of pragmatism allowed however the concessions to run more or less smoothly until the invasion of Karafuto by Soviet Forces in 1945.

Moreover, the territorial waters of the USSR proved to be a contested ground of cooperation between the two states during the interbellum period. Based on a similar system of concessions for oil fields and coal, Japanese fishing fleets could fish in an area spanning from Northern Sakhalin until the Kamchatka and to the frontier with the Alaska[110]. The sea products harvested during this era were salmon, salmon trout, crabs and others (among them cod for its oil). Whaling was practiced as in the arctic waters of the Soviet Union, where whales came during hotter months to fatten up and to feed on microplankton rich waters in the area. Regulation was bound however a little more difficult since Japan benefited from a better whaling material in Soviet waters, and the distance from the shores hindered the Soviet authorities to control closely the activity of fishermen and whalers[111]. As we are going to see, the situation further degraded with the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937.