Why does Swiss history matter to global history?

Published:: 2021-10-07

Author:: William Favre

Topics:: [Swiss] [Military history] [Economic history] [Global history]

[1] Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Aux origines de l’histoire globale, Paris, Collège de France : Fayard, 2014, p.16.

[2] Anne-Lise Head-König, “L'inversion des flux migratoires”, in : Population, View article, viewed on the 01.12.2021.

Introduction

When one thinks of global history, Switzerland isn’t often the first country that comes to mind. The countries usually evoked are mainly located in historical main trade routes such as India, Indonesia or France [1]. We can easily think of the Silk Road, both terrestrial or maritime or later routes that were opened with the violent integration of the Americas into the global trade routes. Moreover, most of them were military and political powers controlling a portion of these and basing their might on mainly technological and military tools.

In this global landscape, Switzerland seems to occupy a marginal spot. Being at the heart of Europe and the Alps, the country is landlocked and thus possibly losing potential dominant position in trade given by the sea, unlike the United Provinces, nowadays Netherlands. Moreover, demographically and territorially speaking, Switzerland has been a secondary power, besides during the late Middle Ages. Historically, before the 19th century, Switzerland was a region of emigration rather than one of immigration due to a lack of perspective of labor for the local population [2]. Hence, the Swiss were seeking outside better opportunities for a living.

Given all these arguments, why would we take the history of Switzerland into consideration through the lens of global history? The main argument in favor of the stance is that the country and the regions closely related to its history occupy an important position in different subjects of global history. Moreover, to understand the extension of one particular history which is connected to Switzerland, one might take a closer look at every link of that transnational network. To put the lessons of Swiss history on the global stage even further, that very history comes with particularities of its own.

However, this short essay’s intention is to contribute to the field of global history by completing some points that may have been overlooked by scholars. Hence the purpose of this short essay is to show a few these canals connecting Switzerland’s history to global history.

In this global landscape, Switzerland seems to occupy a marginal spot. Being at the heart of Europe and the Alps, the country is landlocked and thus possibly losing potential dominant position in trade given by the sea, unlike the United Provinces, nowadays Netherlands. Moreover, demographically and territorially speaking, Switzerland has been a secondary power, besides during the late Middle Ages. Historically, before the 19th century, Switzerland was a region of emigration rather than one of immigration due to a lack of perspective of labor for the local population [2]. Hence, the Swiss were seeking outside better opportunities for a living.

Given all these arguments, why would we take the history of Switzerland into consideration through the lens of global history? The main argument in favor of the stance is that the country and the regions closely related to its history occupy an important position in different subjects of global history. Moreover, to understand the extension of one particular history which is connected to Switzerland, one might take a closer look at every link of that transnational network. To put the lessons of Swiss history on the global stage even further, that very history comes with particularities of its own.

However, this short essay’s intention is to contribute to the field of global history by completing some points that may have been overlooked by scholars. Hence the purpose of this short essay is to show a few these canals connecting Switzerland’s history to global history.

Photo 1: Lavaux Vineyard Terraces (Switzerland), World Heritage (UNESCO), UNESCO, Wikimedia commons, View original image, consulted 04/12/2021.

[3] Anne-Lise Head-König, “Les causes de départs”, in : Émigration, View article, viewed on the 01.12.2021

[4] Gilbert Coutaz, « Lavaux, une terre de convergences », Revue historique vaudoise, vol. 126, 2018, p. 31-44

Fortune from abroad

Until recently in its history, Switzerland was mainly a country of emigration then the opposite, the situation switched during the last quarter of the 19th century with the development of the domestic economy and tourism. From the late middle ages to the French Revolution, the populations living in the area made a living principally of three sources: mountain produces, transalpine commerce and mercenaries [3]. The regional economy was mainly shaped by the low productivity of the mountainous landscape covering 70% of the country. The relief was actually too abrupt to turn them into fields, unless by heavy investments in capital and human work, such as the vineyards in terraces of Lavaux on the shores of Lake Geneva [4].

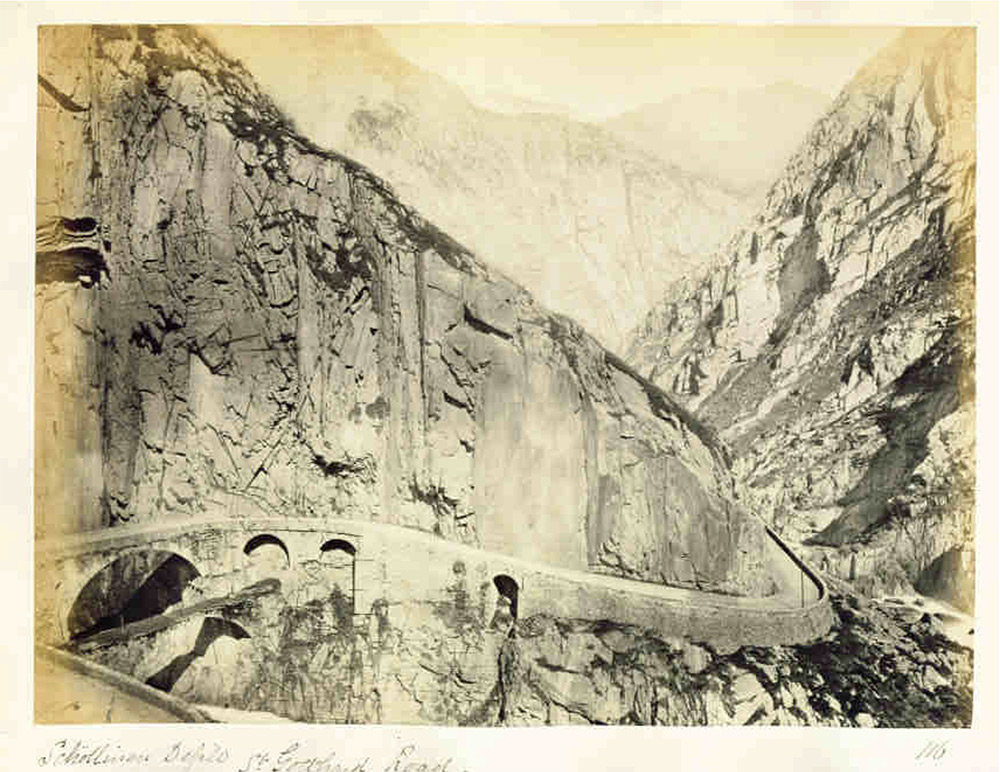

Photo 2: A postcard of the Gothard in the 19th century, Francis Frith (1822-1898), "St. Gothard road". Catalogue number: 116. View original picture.

[5] Aerni, Klaus: "Cols", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version du 27.09.2010, traduit de l’allemand. View article, consulted the 01.12.2021.

Due to this low productive potential, the local societies turned themselves to pastoralism by raising bovine, ovine and caprine stocks. The byproducts of this livestock were then turned into trade products sold through transalpine trade routes to the neighboring territories like Italy, France or Germany by the commercial hubs based in the Plateau, representing 20% of the total land area (Zurich, Luzern or Bern). The second option is to make revenues from the tolls taken at strategic mountain passes through the Alps under Confederate control [5]. Most passes are linking territories situated at both ends of the alpine mountain on a North-South axis, relating Italy to German-speaking kingdoms and France to the West. We can cite the mountain passes of the Great-Saint-Bernard or the Saint-Gotthard among others.

[6] Czouz-Tornare, Alain-Jacques: "Mercenaires", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version du 19.05.2011. View article, consulted 01.12.2021.

[7] François Walter, Une histoire de la Suisse, Neuchâtel [Charenton-le-Pont], Éditions Alphil-Presses universitaires suisses [FMSH diffusion], 2016, pp. 59-60.

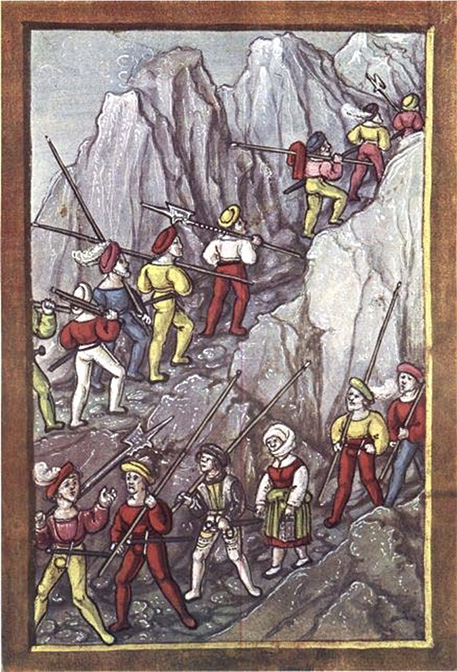

Photo 3: Swiss mercenaries traversing the Alps. Following the capture of Cremona (1509) in the War of the League of Cambrai, Swiss mercenaries desert the French army and walk home. Diebold Schilling the Younger (1460-1515?), Luzerner Chronik, fol. 327v.. Source, consulted 02/12/2021.

The last option is mercenaryism, meaning that a part of the masculine adult population of local societies are searching for employment outside of their native communities as soldiers in neighboring countries. Switzerland becomes thus between the 14th and the 18th a pool of potential and trained soldiers, individually or collectively. Two powerful reasons are alimenting the system of mercenaryism outside of Helvetic lands. One, the Swisses acquired through a series of battles during at the turn of the Middle Ages and the Modern Times the reputation of being competent and ferocious soldiers (the Battle of Morgarten in 1315 and Grandson in 1476). Based on this reputation and with separate treaties, neighboring powers recruit a certain number of units as auxiliary forces in their military contingents [6]. France signed the treaty of Geneva for example in 1515 with Switzerland after the Battle of Marignano where the French troops beat the Swiss forces leading to “perpetual peace” with Switzerland [7]. Two, being a mercenary can be a means for young adults to find more interesting working perspectives in a context of rare opportunities and low wages. Moreover, some mercenaries sought adventure in contrast with a more peaceful lifestyle back in their home valley. Plus, the mercenaries coming home after a few years of military service can be a method to bring capitals to their home village and a sociological means to a prevalent social status with the prestige of their voyage under different banners.

[8] Ibid, pp. 56-7.

[9] Ostinelli, Paolo: "Italie, guerres d'", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version du 17.02.2011, traduit de l’italien. View article, consulted 01.12.2021.

Thanks to the canals of mercenaryism, a network of human flux can be traced from the Old Confederation to different branches spanning in all Europe by units participating to major battles of the Early Modern era [8]. We can cite for example the contingents of Swiss soldiers enrolled by different Italian cities during the Italian Wars of the 16th century [9]. We will see that only population but economic or intellectual fluxes transiting or having nodes in Switzerland.

[10] Körner, Martin; Cassis, Youssef: "Banques", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version du 17.08.2006. View article, consulted 01.12.2021.

[11] Rédaction, La: "Necker, Jacques", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version du 15.01.2009. View article, consulted 02.12.2021.

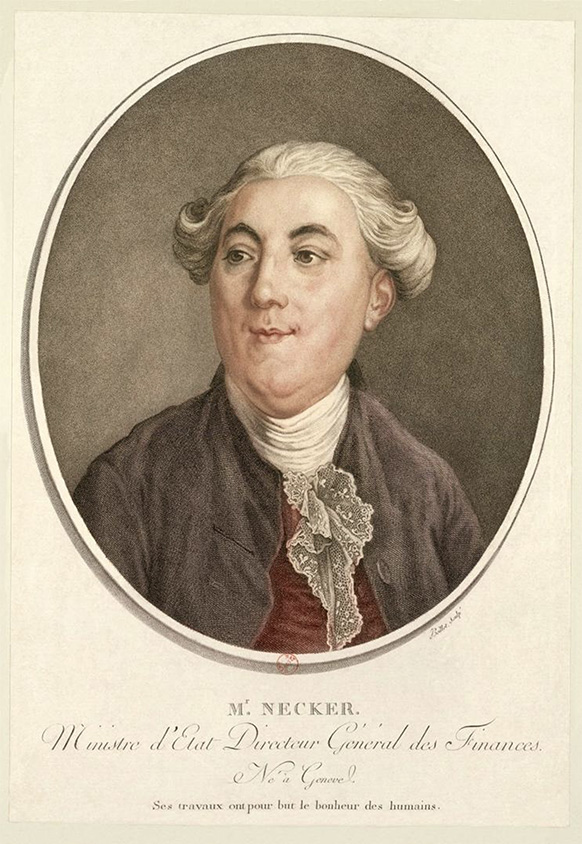

Photo 4: Jacques Necker (1732-1804), State Minister under king Louis XVI of France in 1789, engraved by Boillet, 1789, 31.5x22.5 cm, National Library of France (BNF).

Financial globality

In 1777, the Genevan banker Jacques Necker (1723-1804) became the general director of the Finances of the Kingdom of France. How come that a foreign banker occupied such an important function in the French royal administration? It is in fact the sign of the interconnection of the financial web stretching from territories located in present-day Switzerland [10]. The choice of Necker is even more logical considering the fact that a great part of the French Kingdom’s debt was detained by Genevan bankers. However, a significant number of the creditors went bankrupt as a consequence of the French Revolution broke out in 1789, due partially to the worsening financial state of France despite of Necker’s efforts to fix the state’s finances before being put out of office in 1790 [11].

[12] Altorfer, Stefan; Mazbouri, Malik: "Marché financier", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version du 18.02.2010, traduit de l’allemand. View article, consulted 02.12.2021.

[13] F. Walter, Une histoire de la Suisse, op. cit., pp. 155-6.

[14] Patricia Purtschert et Harald Fischer-Tin??, Colonial Switzerland: Rethinking Colonialism from the Margins, s.l., 2015, pp.5-10.

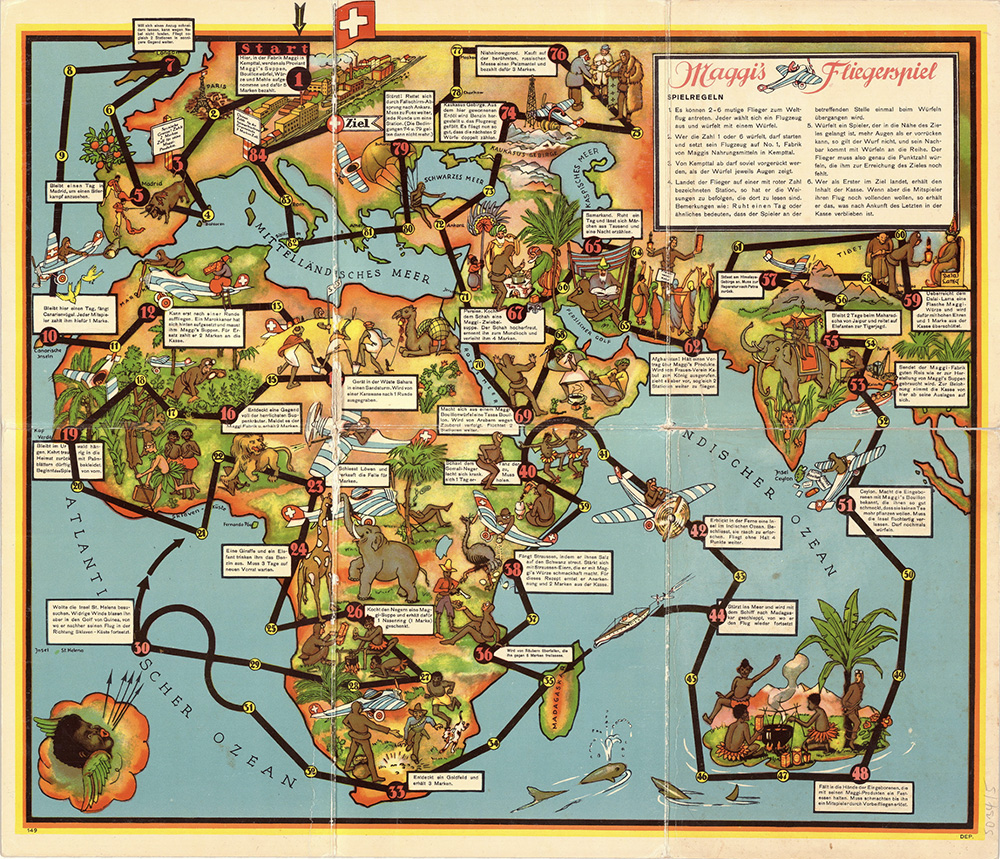

Photo 5: Maggi Fliegerspiel [The Maggi flying boardgame], Maggi ldt, 1930-40, 48X55 cm, photo by L. Ciompi, View original. The game illustrates how colonialism was shaping minds in the first half of the 20th century.

Between the 17th and the 18th century, the nascent Swiss financial system is characterised by an exportation of capitals on exterior financial networks. Investing in the French state debt was among one of these investing points. The financial system is principally located in the Plateau (Flachland) geographic region, where city-states like Geneva, Zurich and Saint-Gallen saw a few families of successful merchants converting into private banking.

The particular path of the financial markets in Swiss cantons originated by the good health of public finances in Switzerland, leading to excedentary capitals to invest. The problem is that the domestic market was too small for the excedents, directing the fluxes to wider market where investing was easier [12].

The main outlet for Swiss private investors are in state obligations of neighboring states such as Austria, Savoy and even the United States – at least the territory of the Thirteen Colonies. In addition to state obligations, private bankers invested as well in global trade networks spanning trades like the Triangular Commerce in the sectors of slavery and plantations. In a larger term, the Old Confederation and the current Confederation starting in 1848 are participating more indirectly to European colonisation by using the Colonial powers connected to Switzerland as a proxy to access these trades [13]. We can consider the Swiss states as peripheral colonial power because they hadn’t any formal colonies. Swiss colonialism is characterised hence by that indirect participation to the colonisation through the means of finances or human fluxes [14].

The particular path of the financial markets in Swiss cantons originated by the good health of public finances in Switzerland, leading to excedentary capitals to invest. The problem is that the domestic market was too small for the excedents, directing the fluxes to wider market where investing was easier [12].

The main outlet for Swiss private investors are in state obligations of neighboring states such as Austria, Savoy and even the United States – at least the territory of the Thirteen Colonies. In addition to state obligations, private bankers invested as well in global trade networks spanning trades like the Triangular Commerce in the sectors of slavery and plantations. In a larger term, the Old Confederation and the current Confederation starting in 1848 are participating more indirectly to European colonisation by using the Colonial powers connected to Switzerland as a proxy to access these trades [13]. We can consider the Swiss states as peripheral colonial power because they hadn’t any formal colonies. Swiss colonialism is characterised hence by that indirect participation to the colonisation through the means of finances or human fluxes [14].

[15] F. Walter, Une histoire de la Suisse, op. cit., p. 388.

In other words, the global history’s debate can be nourished from its financial side by the contribution of less known countries. By looking away from the major states on the geopolitical stage, we may see how smaller territories could insert and participate in these networks shaped by bigger entities. Swiss investments in European colonialism is a perfect testimony of the indirect road taken by minor actors to take part in long-distance trade.

The situation was even reinforced after WWI when Switzerland became a real hub for the global banking system due its economic and political stability. The country became not only a major actor of the financial sector but one of its main stages [15].

The situation was even reinforced after WWI when Switzerland became a real hub for the global banking system due its economic and political stability. The country became not only a major actor of the financial sector but one of its main stages [15].

[16] William Cronon (ed.), Uncommon ground: toward reinventing nature, 1st ed., New York, W.W. Norton & Co, 1995, 561 p.

[17] Switzerland's ecological footprint | Federal Statistical Office (admin.ch), consulted 03/12/2021.

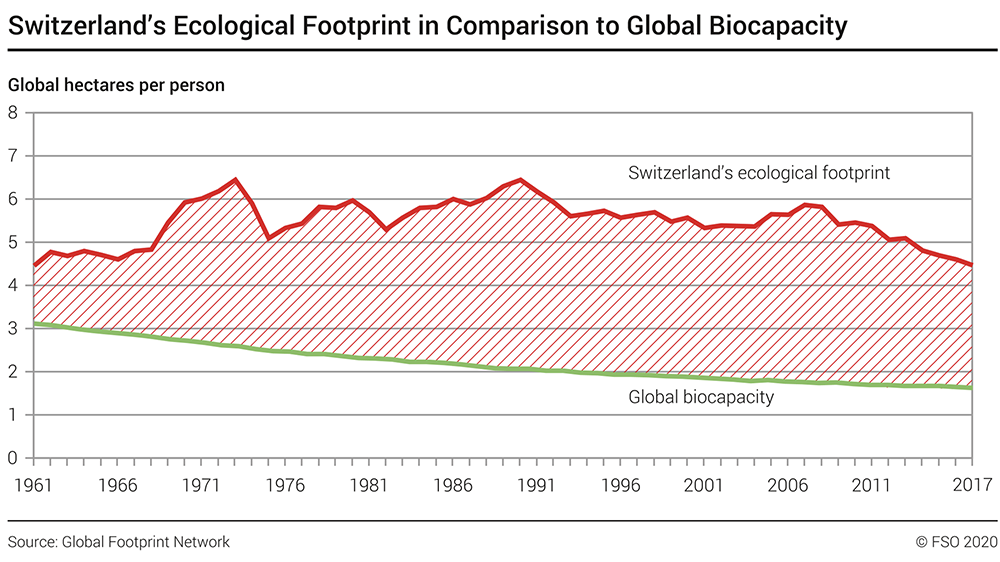

Chart 1: Switzerland’s Ecological Footprint in Comparison to Global Biocapacity, Switzerland's Ecological Footprint in Comparison to Global Biocapacity - Global hectares per person - 1961-2017 | Diagram | Federal Statistical Office (admin.ch)

Impact beyond frontiers

One angle which is less commonly chosen by scholars to treat Switzerland’s history from a global perspective is environmental history. Environmental history is indeed a good candidate to consider how such a small country has a disproportionate impact on global environmental trends than vaster and more populous territories [16].

The ecological footprint of the Swiss is equivalent each year to three Earths [17]. The environmental impact of the Swiss population is largely dependent on the lifestyle in hegemony.

The ecological footprint of the Swiss is equivalent each year to three Earths [17]. The environmental impact of the Swiss population is largely dependent on the lifestyle in hegemony.

Chart 2: Composition of the Ecological Footprint of Switzerland (2017). Composition of Switzerland's Ecological Footprint - In percent - 2017 | Diagram | Federal Statistical Office (admin.ch)

[18] OECD, View article, consulted 02/12/21.

Chart 3: Imports by goods for Switzerland in 2020, Import, Export | Federal Statistical Office (admin.ch), consulted 03/12/2021.

Similarly to other late-developing European countries, the economic development of Switzerland really began in the second half of the 19th century along with its industrialisation. The trend accelerated during the Cold War leading to the current situation: the GDP per capita of Switzerland is one of the highest in the world and was of 71705 USD in 2020 [18]. This economic prosperity and the living standards coming with it is made at the expense of other regions of the world and of the environment.

Due to its poverty in ressources, Switzerland is forced to rely heavily on international trades and imports to maintain its economy up and running. The most dependent types of merchandise were in 2020 precious metals and gems followed by chemical and pharmaceuticals. Alimentary products and energetic products were only 7th and 10th on the list counting respectively for 11’140’000’000 and 5’620’000’000 CHF worth of value (see chart below).

Due to its poverty in ressources, Switzerland is forced to rely heavily on international trades and imports to maintain its economy up and running. The most dependent types of merchandise were in 2020 precious metals and gems followed by chemical and pharmaceuticals. Alimentary products and energetic products were only 7th and 10th on the list counting respectively for 11’140’000’000 and 5’620’000’000 CHF worth of value (see chart below).

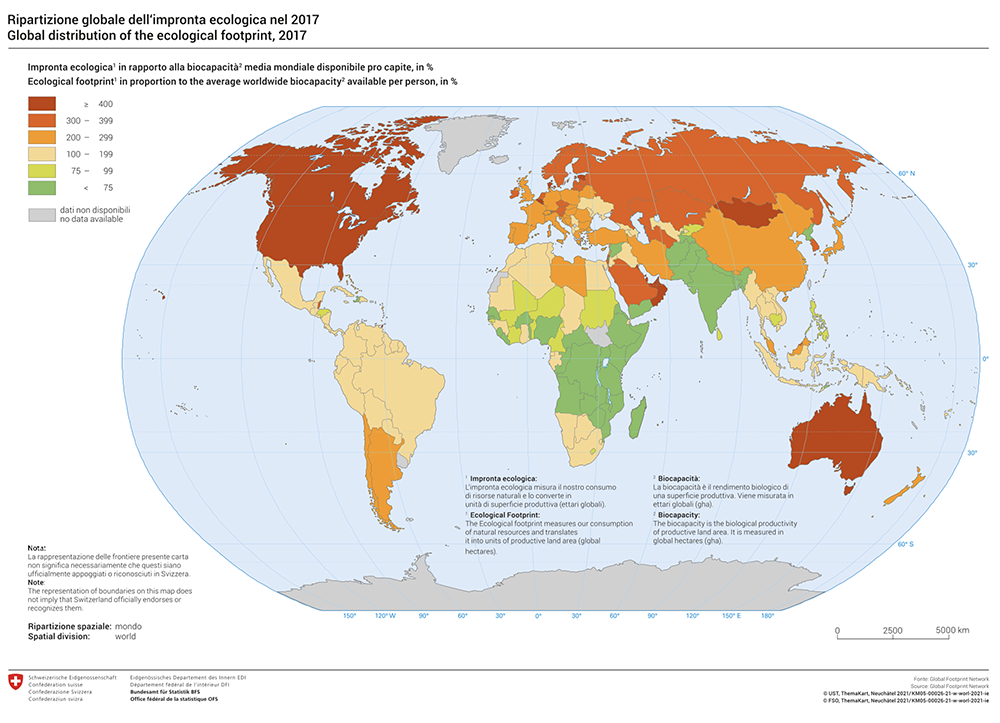

Map 1: Map of the Global distribution of the ecological footprint, 2017, Global distribution of the ecological footprint (World) | Map | Federal Statistical Office (admin.ch)

On one hand, this reliance on global trade markets lowers the resilience of the domestic economy and on the other hand produces a significant amount of CO2 impacting mainly developing countries. This unbalanced situation is called climate injustice because the less impacted regions by climate change are the ones which contribute the most to it.

[19] ATS, “La Suisse pollue surtout à l’étranger » [Switzerland pollutes mostly abroad] View article, consulted on the 04/12/2021.

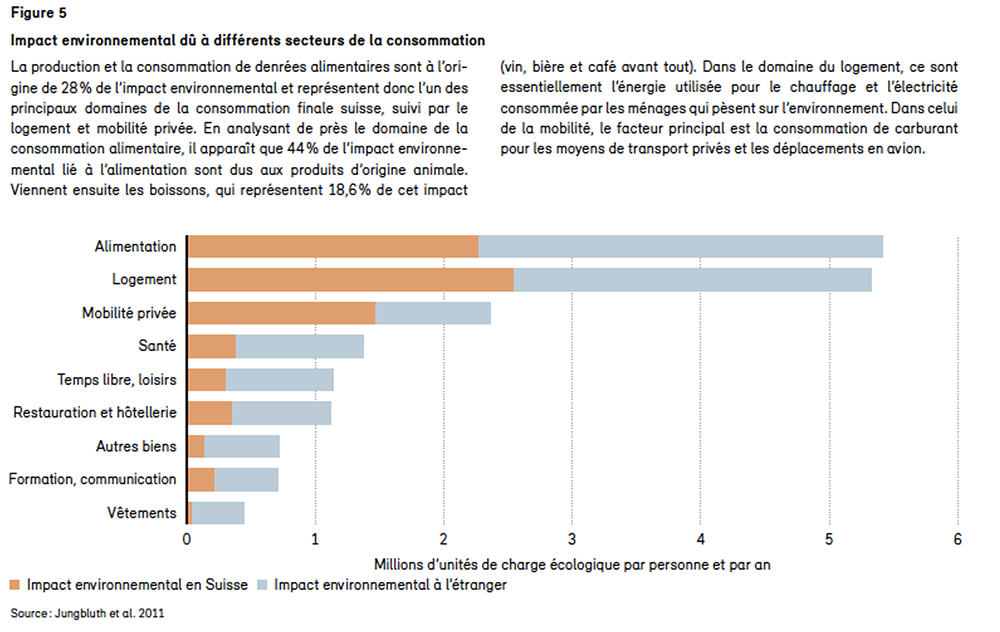

Chart 4: Environmental impact due to different consumption sectors, Swiss Department of Environment, in: Report environment Switzerland 2018, p. 32.

The most tragic component of climate injustice from Switzerland is the projection on the rest of the world of its CO2 production. The 9/10th of yearly environmental impact made by the Swiss population takes its source outside its frontier [19]. The distribution of this impact is then unequally parted between the different regions of the world, the lion’s share going to the territories producing and manufacturing the goods for Switzerland’s market. It becomes difficult to track down precisely the local part taken by the Confederation from other countries because they tend to blend into the complexities of the global trade networks.

[20] François Walter, Une histoire de la Suisse, Neuchâtel [Charenton-le-Pont], Éditions Alphil-Presses universitaires suisses [FMSH diffusion], 2016, p. 158-164.

[21] View article, consulted 03/12/2021.

Chart 5: Curve of the global temperature of Switzerland compared to the global average between 1860 and 2020, Federal Office for Weather and Climatology, View article, consulted 03/12/2021.

However, this section of central Europe doesn’t make an exception to the global climate variations in the long run. During the Little Ice Age from the 16th to the 19th century, Switzerland saw an increase in size of its glaciers while the local population was suffering from plagues, famines but was quite preserved from war until the Napoleonic Wars [20]. With the beginning of the industrial era in the 19th century, Switzerland has been observing a rapid augmentation of its average temperature during the following century. Climate change, due to the landlocked and alpine situation of the territory, is magnified in Switzerland compared to global average: 2 C° instead of the 1 C° augmentation monitored up until now [21].

[22] Walter, François; Pfister, Christian; Haefeli-Waser, Ueli: "Environnement", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version du 14.01.2014, traduit de l’allemand. View article, consulté le 04.12.2021, 04/12/2021.

[23] Luigi Giorgio, “Amid shortages, can Switzerland stay Europe’s ‘water tower”, Swissinfo.com, View article, consulted 03/12/2021.

[24] Patrick Kupper, Creating wilderness: a transnational history of the Swiss National Park, English language edition., New York, Berghahn, 2014, 266 p, Chapter 3.

What makes the environmental history of Switzerland interesting for the broader debate of environmental history is that the country is on its trajectory, being one of the most severely impacted territories of the world after the polar regions. It distinguishes its trajectory from other countries of the Global North, marginally touched by climate change until now. The most drastic changes in Switzerland proper brought by the environmental effects of the Industrial era are the melting of the main alpine glaciers and the rapid urbanization of Switzerland's population during the last 150 years [22]. This cascade of consequences coming from the profound and rapid evolution put the local and global biosystems under pressure. Connecting the two shards of the same story can help us to understand the intricacies of environmental consequences of the industrialization of rapidly industrializing countries on both local and transnational scale.

To push the argument further, if we want to grasp the bigger picture, we must turn ourselves to overlooked corners of this picture in order to make it clearer and maybe modify our perception of the whole story. Switzerland could be a good candidate for this endeavor for several reasons. Firstly, Switzerland is located at the crossroads of Northern and Southern Europe as well as being the “water tower of Europe" [23], it has thus a strategic role in circulation of the bigger region of Central and Alpine Europe. Secondly, the confederate political system is an oddity on the politological level whose autonomist nature leads each unit of the Confederation to have a trajectory of its own. Finally, the relationship uniting Switzerland and the specific mountain range, Alps, sheds an interesting light on the role of highlands or mountain areas in a global more-than-human and local history [24].

To push the argument further, if we want to grasp the bigger picture, we must turn ourselves to overlooked corners of this picture in order to make it clearer and maybe modify our perception of the whole story. Switzerland could be a good candidate for this endeavor for several reasons. Firstly, Switzerland is located at the crossroads of Northern and Southern Europe as well as being the “water tower of Europe" [23], it has thus a strategic role in circulation of the bigger region of Central and Alpine Europe. Secondly, the confederate political system is an oddity on the politological level whose autonomist nature leads each unit of the Confederation to have a trajectory of its own. Finally, the relationship uniting Switzerland and the specific mountain range, Alps, sheds an interesting light on the role of highlands or mountain areas in a global more-than-human and local history [24].

[25] Pierre Boissier, From Solferino to Tsushima: history of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva, Henry Dunant Institute, 1985, 391 p.

Conclusion

As we could see, Switzerland’s past offers a wide array of angles and approaches to enrich the debates around global history by adding the lessons that could be learned from Swiss history. We limited ourselves to consider only networks that were involving only military and financial movements as well as an environment for Switzerland. There are many more ways to enlarge the discussions on world-level histories by additional points of view, like the role of Switzerland being a neutral country in international relations and by being home to many international organizations like the Red Cross movement [25].

We preferred to avoid these for the reason they seemed already explored points and it looked more profitable to focus our attention on less known areas of Switzerland’s past intertwines as well in transregional networks.

What could be the next steps to explore? This present blog entry was only an aperture for further research and calls only for more exploration on already opened fields like the participation of Switzerland in global imperialism or colonialism or to rather new ones like in the history of scientific networks spanning on a transnational level.

We preferred to avoid these for the reason they seemed already explored points and it looked more profitable to focus our attention on less known areas of Switzerland’s past intertwines as well in transregional networks.

What could be the next steps to explore? This present blog entry was only an aperture for further research and calls only for more exploration on already opened fields like the participation of Switzerland in global imperialism or colonialism or to rather new ones like in the history of scientific networks spanning on a transnational level.

Bibliography

Altorfer, Stefan; Mazbouri, Malik: "Marché financier", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version du 18.02.2010, traduit de l’allemand

Pierre Boissier, From Solferino to Tsushima: history of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva, Henry Dunant Institute, 1985, 391 p.

William Cronon (ed.), Uncommon ground: toward reinventing nature, 1st ed., New York, W.W. Norton & Co, 1995, 561 p.

Anne-Lise Head-König, “L'inversion des flux migratoires”, in : Population

Patrick Kupper, Creating wilderness: a transnational history of the Swiss National Park, English language edition., New York, Berghahn, 2014, 266 p, Chapter 3.

Patricia Purtschert et Harald Fischer-Tin??, Colonial Switzerland: Rethinking Colonialism from the Margins, s.l., 2015 Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Aux origines de l’histoire globale, Paris, Collège de France : Fayard, 2014

François Walter, Une histoire de la Suisse, Neuchâtel [Charenton-le-Pont], Éditions Alphil-Presses universitaires suisses [FMSH diffusion], 2016, p. 158-164.

Walter, François; Pfister, Christian; Haefeli-Waser, Ueli: "Environnement", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version du 14.01.2014, traduit de l’allemand

Anne-Lise Head-König, “L'inversion des flux migratoires”, in : Population

Patrick Kupper, Creating wilderness: a transnational history of the Swiss National Park, English language edition., New York, Berghahn, 2014, 266 p, Chapter 3.

Patricia Purtschert et Harald Fischer-Tin??, Colonial Switzerland: Rethinking Colonialism from the Margins, s.l., 2015 Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Aux origines de l’histoire globale, Paris, Collège de France : Fayard, 2014

François Walter, Une histoire de la Suisse, Neuchâtel [Charenton-le-Pont], Éditions Alphil-Presses universitaires suisses [FMSH diffusion], 2016, p. 158-164.

Walter, François; Pfister, Christian; Haefeli-Waser, Ueli: "Environnement", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version du 14.01.2014, traduit de l’allemand