Of humans and great predators, the case of Switzerland

Published:: 2022-10-28

Author:: William Favre

Topics:: [Environment] [Swiss] [Animals]

[Picture 1] Bearded vulture, Catalan Pyrenees- Spain, 13.02.2016, Francesco Veronesi, consulted on the 10.04.22.

[1] Swiss Radio Television (RTS), Un deuxième loup de la meute de Marchairuz tué dans le canton de Vaud (A second wolf of the Marchairuz pack killed in the canton of Vaud), 01.04.22, consulted on 16.04.22. Reference >>

[2] Perrot, “Passions cynégénétiques. Anthropologie historique du droit de la chasse au grand gibier en France.”, pp. 360-1.

Introduction

In recent years, the return of the wolf (canis lupus) in Switzerland sparked much debate around the behavior that had to be taken in reaction to its presence. The return of the great predators in Switzerland, including the brown bear, the wolf, the lynx and the bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus) either by reintroduction or by natural migration led to mixed feelings in the population in the last decades of the 20th century.

From an environmental standpoint, one could be more than glad to observe the progressive return of once extinct- for more than a century and a half- species, which indicates the slow regeneration of the local ecosystems to a more durable equilibrium. However, it isn’t a point of view shared by the entirety of the population. The most vocal opponents to the current situation are circles of animal husbandry, ovine and bovine or caprine[1]. The main argument issued by the partisans for a strict regulation of the lupine or ursine population is to prevent the predators from hunting on their livestock. From their perspective, the return of superpredators in the alpine region and its surroundings and more generally in Europe shows a continuity with earlier anthropological tendencies[2]. Beyond financial compensation, it seems that the simple elimination of what is seen as a hustle would be the best option.

On the other side, the Swiss government must juggle between the choice of supporting the stricken herders and a significant part of the population who seems favorable for a tolerant policy towards the great predators. We are assisting, most acutely with the wolf, since 1995, the eruption of a fault line between two sides within the population about a question that appears to be mainly political and environmental.

The most pressing question in this heated and ongoing debate is the following: how much space should we leave to great predators? To what extent can we tolerate the predators to circulate in the Swiss territory and behave on their own? These questions are crucial, because it extends beyond the scope of the great predators but to every species of the local ecosystems. To which extent are we willing collectively to leave a vital space for species other than us and our collaborator species. The very survival of the great predators among others lies in the size of the spatial and behavioral margin. As an example, the extinction of the great predators was related to that factor, as we will develop in the first part.

The aim of that essay will be to see if the cohabitation between humans and the great predators is possible for the current situation, with a historical enlightenment. For a geographical scope, we will concentrate on Switzerland, with references taken to neighboring countries since animal mobility ignores human borders. The covered temporal period begins from the 16th century to the 21st century, with a major shift in the 19th century with the dispersion of the great predators, for a certain time. The starting point of the 16th century was chosen due to the change in mentalities coming with the Renaissance, even though we could find some preexisting signs after the first Black Death wave.

From an environmental standpoint, one could be more than glad to observe the progressive return of once extinct- for more than a century and a half- species, which indicates the slow regeneration of the local ecosystems to a more durable equilibrium. However, it isn’t a point of view shared by the entirety of the population. The most vocal opponents to the current situation are circles of animal husbandry, ovine and bovine or caprine[1]. The main argument issued by the partisans for a strict regulation of the lupine or ursine population is to prevent the predators from hunting on their livestock. From their perspective, the return of superpredators in the alpine region and its surroundings and more generally in Europe shows a continuity with earlier anthropological tendencies[2]. Beyond financial compensation, it seems that the simple elimination of what is seen as a hustle would be the best option.

On the other side, the Swiss government must juggle between the choice of supporting the stricken herders and a significant part of the population who seems favorable for a tolerant policy towards the great predators. We are assisting, most acutely with the wolf, since 1995, the eruption of a fault line between two sides within the population about a question that appears to be mainly political and environmental.

The most pressing question in this heated and ongoing debate is the following: how much space should we leave to great predators? To what extent can we tolerate the predators to circulate in the Swiss territory and behave on their own? These questions are crucial, because it extends beyond the scope of the great predators but to every species of the local ecosystems. To which extent are we willing collectively to leave a vital space for species other than us and our collaborator species. The very survival of the great predators among others lies in the size of the spatial and behavioral margin. As an example, the extinction of the great predators was related to that factor, as we will develop in the first part.

The aim of that essay will be to see if the cohabitation between humans and the great predators is possible for the current situation, with a historical enlightenment. For a geographical scope, we will concentrate on Switzerland, with references taken to neighboring countries since animal mobility ignores human borders. The covered temporal period begins from the 16th century to the 21st century, with a major shift in the 19th century with the dispersion of the great predators, for a certain time. The starting point of the 16th century was chosen due to the change in mentalities coming with the Renaissance, even though we could find some preexisting signs after the first Black Death wave.

[Picture 2] Street Performers with Dancing Bear and Monkey [Schausteller mit Tanzbär und Affe

], Gottfried Mind, 1768-1814, watercolor, 20.5x31.8 cm, Swiss National Library, consulted on 01.04.22. This image shows how the danger represented by the bear is “mastered” by the performers.

[3] François Walter, Une Histoire de la Suisse, p.134.

[4] Mathieu, History of the Alps, 1500-1900, p.116.

[5] Hermann Aubin et alii, “Demographics”, in : history of Europe, 09.03.2022, Britannica, consulted on 16.04.22.

[6] We can cite an interlude between two colder periods at the end of the 15th century and the 17th century. It will be followed by the “Small Ice Age” which will continue until the mid-19th century.

[7] Roger Seiler: "Peste", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version of 27.09.2010, translated from German. Online reference >>, consulted on 16.04.2022.

[8] Byrne, Encyclopedia of the Black Death, p. 127.

[9] Crosby, The Columbian Exchange, Chapter 5: "New World Foods and Old World Demography".

[10] François Walter, Les Suisses et l’environnement.

[11] Inspired from the concept of Commodity frontier coined by Jason Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital (London, 2015).

[12] Based on the archival incidence of the documents on predator hunting, in the archives of the cantons of Geneva, Vaud and Valais.

[13] François Walter, Une histoire de la Suisse, pp. 301-4.

[14] van der Leeuw, Social Sustainability, Past and Future, pp.35-6.

The shift of minds in the Early Modern Age

The transition between the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period marks a step in the relation of the human populations of the Old Confederacy to its environment, especially towards its fauna. The tendencies we might observe in the territory of the Old Confederacy can be shared with the rest of the alpine range, provided a few regional nuances[3]. We can mention firstly the introduction of firearms to the population during the end of the Middle Ages, which led to a significant increase of pressure being put upon different types of animals, mostly ungulates and venison[4]. The wider use of firearms by the population, mostly for military purposes or hunting would undermine the prey reserves of the predators, mechanically indirectly impacting their potential food reserves and hence their number.

The second factor is demographic. The population of Europe encountered an increase during what was called the “Beautiful Sixteenth Century”, mostly during the decades of the century. In the territory of what now is Switzerland and its surroundings, the population grew at the rate of 0.6% to 1%. The population of the territory, based on estimations designed on sparse documents, reached 900 '000 inhabitants in the beginning of the 17th century. Elsewhere in Europe, the rate of growth in the population was seemingly similar, leading to multiplication by two of the population, from 65 million to 127 million on the continent between 1500 and 1800[5]. Such an augmentation in European demographics can be explained by various factors, ranging from the momentary stop in the epidemics to a less rude climate compared to late Middle Ages[6].

The third factor was economic. The end of the Middle Ages marked a period of crisis from the point of view of social, economic and political conditions. Such a traumatic period for Europe brought some important changes in the functioning of the continent’s economy[7]. The sudden disappearance of almost a half of the European population and the geopolitical instability lowered significantly the pressure of demography on soils and the surviving skilled workers became relatively rare, allowing a raise in their salary. This transition from medieval to early modern times saw the rise all over the continent of merchants as a loose social group. Over the course of the fifteenth and the sixteenth centuries, the merchants of Europe, from Scandinavia to Italy implemented a proto-capitalist system. This profound and progressive social change was fueled as well by the influx of silver and gold coming from the Colonial Empire of Spain in the Americas, sparking a phenomenon of growth and inflation at the same time[8].

All these factors met to restructure the overall agriculture and animal husbanding, leading to a new way to interact with the environment, interacting with factors such as interconnection with outside political entities and trade. The main trends that would be observed during this period is the intensification of already invested grounds and the extension to new parcels to areas that weren’t the object of previous exploitation. The highlands and the lowlands on the Plateau underwent different transformations. The highlands saw a growth in wood and timber extraction, along with an intensification of cattle raising for inside and outside markets, notably Northern Italy. The lowlands produced a wider variety of crops than the highlands, mainly cereals and vegetables for the farmers’ own consumption, the exportation being reserved for the wealthier ones. Intensification could be channeled with the proto-industrial revolution by an agricultural revolution characterized by the introduction of the potato, corn, the absence of periods of fallow in the fields (with difference depending on the regions) and wave of enclosures[9].

In the chain of consequences, the expansion and the intensification of human activities would impede the vital space of the great predators, indifferently from highlands or lowlands[10] Human interference into the territory of the wolf or the brown bear (Ursus arctos) represented a source of nuisance and destruction to their habitat, chasing out progressively these animals to the margins of an inexorably expanding “crop frontier”[11]. The superposition of human and superpredator living areas would create tensions, mostly around the stakes of forests (timber versus shelter) and livestock. Based on the sources, most of the tensions occurred during the Early Modern era in the Alpine range, in the cantons of Valais and Grisons[12]. The explanation could be that the “crop frontier” would situate there and that the human encroachment on the steep slopes of the Alps was less harsh than in the Plateau.

The last link in the chain was cultural. Indeed, we observe during the Early Modern period a shift in the attitude, with local particularities, of the inhabitants of the Confederate States towards their environment[13]. The rise of proto-capitalism and secularization would be two driving factors in the shift from a moralist vision of Nature to a mechanist, pragmatic vision of the environment. In this perspective, the environment became an outside reality from which resources could be extracted or a directory principle ordering the Universe, from the metaphysical point of view[14].

The second factor is demographic. The population of Europe encountered an increase during what was called the “Beautiful Sixteenth Century”, mostly during the decades of the century. In the territory of what now is Switzerland and its surroundings, the population grew at the rate of 0.6% to 1%. The population of the territory, based on estimations designed on sparse documents, reached 900 '000 inhabitants in the beginning of the 17th century. Elsewhere in Europe, the rate of growth in the population was seemingly similar, leading to multiplication by two of the population, from 65 million to 127 million on the continent between 1500 and 1800[5]. Such an augmentation in European demographics can be explained by various factors, ranging from the momentary stop in the epidemics to a less rude climate compared to late Middle Ages[6].

The third factor was economic. The end of the Middle Ages marked a period of crisis from the point of view of social, economic and political conditions. Such a traumatic period for Europe brought some important changes in the functioning of the continent’s economy[7]. The sudden disappearance of almost a half of the European population and the geopolitical instability lowered significantly the pressure of demography on soils and the surviving skilled workers became relatively rare, allowing a raise in their salary. This transition from medieval to early modern times saw the rise all over the continent of merchants as a loose social group. Over the course of the fifteenth and the sixteenth centuries, the merchants of Europe, from Scandinavia to Italy implemented a proto-capitalist system. This profound and progressive social change was fueled as well by the influx of silver and gold coming from the Colonial Empire of Spain in the Americas, sparking a phenomenon of growth and inflation at the same time[8].

All these factors met to restructure the overall agriculture and animal husbanding, leading to a new way to interact with the environment, interacting with factors such as interconnection with outside political entities and trade. The main trends that would be observed during this period is the intensification of already invested grounds and the extension to new parcels to areas that weren’t the object of previous exploitation. The highlands and the lowlands on the Plateau underwent different transformations. The highlands saw a growth in wood and timber extraction, along with an intensification of cattle raising for inside and outside markets, notably Northern Italy. The lowlands produced a wider variety of crops than the highlands, mainly cereals and vegetables for the farmers’ own consumption, the exportation being reserved for the wealthier ones. Intensification could be channeled with the proto-industrial revolution by an agricultural revolution characterized by the introduction of the potato, corn, the absence of periods of fallow in the fields (with difference depending on the regions) and wave of enclosures[9].

In the chain of consequences, the expansion and the intensification of human activities would impede the vital space of the great predators, indifferently from highlands or lowlands[10] Human interference into the territory of the wolf or the brown bear (Ursus arctos) represented a source of nuisance and destruction to their habitat, chasing out progressively these animals to the margins of an inexorably expanding “crop frontier”[11]. The superposition of human and superpredator living areas would create tensions, mostly around the stakes of forests (timber versus shelter) and livestock. Based on the sources, most of the tensions occurred during the Early Modern era in the Alpine range, in the cantons of Valais and Grisons[12]. The explanation could be that the “crop frontier” would situate there and that the human encroachment on the steep slopes of the Alps was less harsh than in the Plateau.

The last link in the chain was cultural. Indeed, we observe during the Early Modern period a shift in the attitude, with local particularities, of the inhabitants of the Confederate States towards their environment[13]. The rise of proto-capitalism and secularization would be two driving factors in the shift from a moralist vision of Nature to a mechanist, pragmatic vision of the environment. In this perspective, the environment became an outside reality from which resources could be extracted or a directory principle ordering the Universe, from the metaphysical point of view[14].

[Picture 3] Flag of the canton of Bern, symbolizing a bear, URL: Wikimedia commons, consulted the 28.03.22.

[15] Morenzoni Franco. Note sur la présence de l'ours en Valais et dans le Chablais vaudois à la fin du Moyen Age. In: L'homme et la nature au Moyen Âge. Paléoenvironnement des sociétés occidentales. Actes du Ve Congrès international d'Archéologie Médiévale (Grenoble, 6-9 octobre 1993) Caen : Société d'Archéologie Médiévale, 1996. pp. 153-156. (Actes des congrès de la Société d'archéologie médiévale, 5), p.

[16] Michel Pastoureau, L’ours. Histoire d’une déchéance, p. 264.

[17] In celtic languages, the name Brennos could be an anthroponym meaning “leader, souverain” or the crow, an avatar of the god Lug in celtic mythology. Onlice reference >>, consulted on the 17.04.22.

[18] Sylvie Bazzanella, « Historique de la Fosse aux ours de Berne », in : NotreHistoire.ch, 10.02.14, consulted on the 17.04.22.

The early modern mentality towards animals was different from nowadays and was in fact a prolongation of the cultural tendencies that we could see during the Middle Ages[15]. The bear, for example and as underlined by Michel Pastoureau, was considered as the King of Animals before being dethroned by the lion during the later centuries of the Middle Ages[16]. In this regard, the overall degradation of the population’s opinion toward the bear was the fruit of centuries of denigration by hegemonic Christian theology, losing the primacy it had for the first period of the Middle Ages. Indeed, the bear occupied a significant space in the local cultures.

One example is the etymology of the city-state of Bern, whose origins remain murky. The toponym of Bern predates the installation of Germanic tribes in the area, of the end of the 3rd century CE. A zinc plate found during excavations in the city of Bern allowed archeologists to theorize that it could have a Celtic origin. The plate mentions the toponym of Brenodurum, or the “oppidum of Brennos”[17]. Beyond a savory historical misunderstanding, this interpretation of that toponym could be an illustration of the city’s influence and might. It is no wonder if the bear appears on the flags of at least three cantons: Appenzell Inner and Outer Rhodes and the one of Bern. Despite following a slow decay in Europe in the cultural representations, the bear kept for instance an ambivalent position, either revered or feared. The Bärengraben or the “Bear Pit” was a dug-up space where bears were detained as an incarnation of the city’s value as well as a spoil of war[18].

One example is the etymology of the city-state of Bern, whose origins remain murky. The toponym of Bern predates the installation of Germanic tribes in the area, of the end of the 3rd century CE. A zinc plate found during excavations in the city of Bern allowed archeologists to theorize that it could have a Celtic origin. The plate mentions the toponym of Brenodurum, or the “oppidum of Brennos”[17]. Beyond a savory historical misunderstanding, this interpretation of that toponym could be an illustration of the city’s influence and might. It is no wonder if the bear appears on the flags of at least three cantons: Appenzell Inner and Outer Rhodes and the one of Bern. Despite following a slow decay in Europe in the cultural representations, the bear kept for instance an ambivalent position, either revered or feared. The Bärengraben or the “Bear Pit” was a dug-up space where bears were detained as an incarnation of the city’s value as well as a spoil of war[18].

[Picture 4] Photograph of the bear pit in Bern, around 1900, by Photochrome print collection, posted 2014, consulted on 02.04.2022.

[19] XXX

[20] Jon Mathieu, The History of the Alps

[21] OFEV, «Faune, chasse et protection: « Il nous faut une large alliance pour les animaux sauvages » (“Fauna, game and protection : “We need to make a large alliance for wildlife), 17.02.2016,Online reference >>, consulted on 16.04.22.

The other predatory animals didn’t have such a desirable fate, the wolf was considered generally during the medieval times and well beyond as a nefarious animal. We can quote the infamous reputation of the wolf in fairy tales, the figure of the Big Bad Wolf[19]. Moreover, the largely pastoralist way of life from mountaineers in the Alps didn’t help either to improve the general image of the wolf. The animal would be seen as a burden to cope with, threatening directly the wealth of the pastoralists when their livestock was eaten by predators[20]. The problem would be aggravated by human encroachment in the traditional living space of the bear and the wolf, while the number of wildlife prey was dwindling due to human hunting, which will become a real problem later during the 19th century[21]. The margin of tolerance towards the great predators decreased, representing a good testimony of relationship to the environment. The hold of proto-capitalism transformed progressively livestock into a source of income in addition to foodstuff, a property; the predators would be seen as “stealing” in some way the owner of the livestock.

[Picture 4] Image of the last bear killed in Switzerland, in the Engadin Valley in 1904, in “Histoire de l’ours en Suisse”, Unknown, Online reference >>, 10.04.22.

[22] Yvonne Boerlin-Brodbeck: "Romantisme", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version of 12.01.2012, translated from German. Online reference >>, consulted on the 16.04.

[23] Thiesse, La Création Des Identités Nationales, p. 521.

[24] Alexandre Scheurer, « Histoire du loup en Suisse romande », in : Passé Simple, 2019, pp. 5-6 ;9.

[25] Béatrice Veyrassat: "Industrialisation", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version of the 11.02.2015. Online reference, consulted on 16.04.2022.

The extinction of great predators

The end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century marked the disappearance of the great predators in Swiss territory and for at least a century. The main environmental event was the biodiversity crisis that struck the whole territory at the same period. As we would see, industrialization and the amelioration of firearms are no stranger to that phenomenon. Paradoxically, the 19th century would observe the rise of a new sensibility towards Nature and the environment, with the emergence of art cultural movements like romanticism[22]. With the development of nationalisms, tourism and capitalist industrialism, the environment began bearing new social functions like leisure and sightseeing. During the 19th century, the term Heimat or “Land of Origin” would carry a great significance in the human-environment relationship[23].

The last bear in Switzerland was killed in 1904 in the Engadin Valley, which closed the strong signal of the decline of wildlife in general in Switzerland during the timespan separating this moment from the first signs of industrialization at the end of the 18th century. The significant reduction of non-anthropized spaces is the translation of a major social shift in Switzerland and the social fragility of rural economies[24]. The modern federal state emerged partly due to industrialization in 1848 and in return fueled a first boost in industrialization in the 1860’s. The two decades of 1860 and 1870 correspond to a blooming period for the Swiss economy, where growth actually took up, after a long preparation that began during the Early Modern period with proto-industrialization[25]. It is also the key-period when Switzerland’s economy- its material reality- was driven formerly by the primary sector (agriculture, mining, resource extraction) but was soon replaced by industry, the sector of resource transformation. Such an economic prosperity was nourished by the centralization and the internal unification of the country after the emergence of Modern Confederation.

The last bear in Switzerland was killed in 1904 in the Engadin Valley, which closed the strong signal of the decline of wildlife in general in Switzerland during the timespan separating this moment from the first signs of industrialization at the end of the 18th century. The significant reduction of non-anthropized spaces is the translation of a major social shift in Switzerland and the social fragility of rural economies[24]. The modern federal state emerged partly due to industrialization in 1848 and in return fueled a first boost in industrialization in the 1860’s. The two decades of 1860 and 1870 correspond to a blooming period for the Swiss economy, where growth actually took up, after a long preparation that began during the Early Modern period with proto-industrialization[25]. It is also the key-period when Switzerland’s economy- its material reality- was driven formerly by the primary sector (agriculture, mining, resource extraction) but was soon replaced by industry, the sector of resource transformation. Such an economic prosperity was nourished by the centralization and the internal unification of the country after the emergence of Modern Confederation.

[Picture 6] Photography of a hillside under road construction, early 20th century, Swiss National Library, consulted 30.03.22.

[26] Agnoletti and Neri Serneri, The Basic Environmental History, p. 24.

[27] Christopher Jones, Routes of Power.

[28] Katja Hürlimann: "Industrie du bois", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version of 08.01.2008, translated from German. Online reference >>, consulted on 20.04.2022

[29] François Walter, Une histoire de la Suisse, p. 304.

The flipside of the coin were the material implications of the industrialization of the Swiss economy and society. An economy majorly driven by the transformation of resources needed different prerequisites: a great influx of primary resources, energy, foodstuff and finally infrastructure[26]. The augmentation of all these indicators had major repercussions on the local environment, mostly when the origin of the resources came from the national territory or its vicinity, mostly by a larger extraction. Among those, we ought to mention fueling material, furnishing the primordial energy to the technologies allowing the transformation of the primary resources. The industrial age was based majorly on stocks, not on fluxes as underlined Pr. Christopher F. Jones. The use of coal for fuel began to really take off in the middle of the 19th century[27]. Wood for heating until this period but represented a bottleneck for the case of Switzerland. The capacity of a local forest was overwhelmed by Swiss consumption already by 1800[28]. This situation led to an overexploitation of the native forests and could only be relieved by the importation of foreign coal. As a consequence, the logging industry is experiencing an augmentation with the growth of the different sectors needing wood outside of energy as building material, especially in the railways, the furniture industry and for other objects of everyday life.

Railways, roads and tunnels had powerful effects on landscapes and the accessibility of until then remote areas, mostly in the Alps. Besides the need of construction material, the modification of the landscapes was profound due to the leveling of hillsides or slopes or the piercing of tunnels. The bulk of the railways built before World War I were concentrated in the Plateau and represented a factor of habitat fragmentation for the native species, for lowland forests. Paradoxically, the effect of the establishment of a transportation network during this period was inversely proportional to its concentration. The heaviest concentration of the landscape modification was found in the most rugged landscapes in the cantons of Valais, Ticino, Graubünden and Jura[29]. The high amount of energy and capital required for the installation of roads or railways had important effects along the line by cutting the territory of the local species and its global shape. Most importantly, the integration of once hardly accessible localities could transform the functioning of such regions, lifting partially the boundaries of geography and topography.

Railways, roads and tunnels had powerful effects on landscapes and the accessibility of until then remote areas, mostly in the Alps. Besides the need of construction material, the modification of the landscapes was profound due to the leveling of hillsides or slopes or the piercing of tunnels. The bulk of the railways built before World War I were concentrated in the Plateau and represented a factor of habitat fragmentation for the native species, for lowland forests. Paradoxically, the effect of the establishment of a transportation network during this period was inversely proportional to its concentration. The heaviest concentration of the landscape modification was found in the most rugged landscapes in the cantons of Valais, Ticino, Graubünden and Jura[29]. The high amount of energy and capital required for the installation of roads or railways had important effects along the line by cutting the territory of the local species and its global shape. Most importantly, the integration of once hardly accessible localities could transform the functioning of such regions, lifting partially the boundaries of geography and topography.

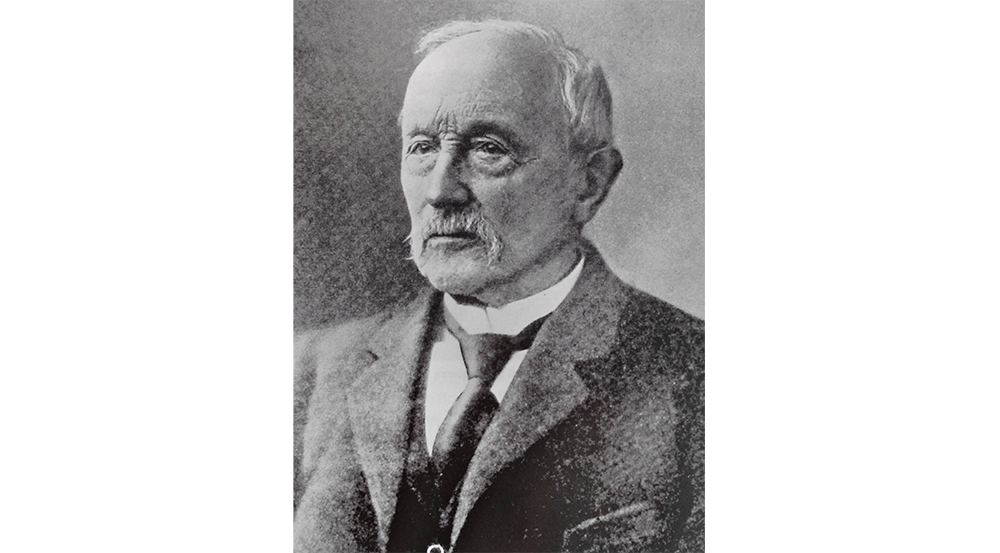

[Picture 7] Portrait of Johann Wilhelm Fortunat Coaz, around 1890, Unknown author, Online reference >>, consulted on 30.03.22.

[30] Stephanie Summermatter: "Nature, protection de la", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version of 07.09.2010, translated from German. Online reference >>, consulted on 20.04.2022.

[31] Kupper, Creating Wilderness, p. 40.

[32] François Walter, Une histoire de la Suisse, part. III.

[33] Anton Schuler: "Forêt à ban", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version of 20.03.2015, translated from German. Online reference >>, consulted on 24.04.2022

[34] Anton Schuler: "Coaz, Johann Wilhelm Fortunat", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version du 20.01.2020, translated from German. Online reference >>, consulted on 20.04.2022.

All those social evolutions wrought by industrialization provoked the biodiversity crisis that eventually wiped out the great predators and a good part of Switzerland's forest fauna. In parallel to the environmental devastation that the local ecosystems experience, the pace of the degradation was severe enough to re-implement strong measures in order to hinder the ongoing trend of the time. By re-implementing, it has to be understood as a return to a more severe regulation by the State concerning hunting, poaching and forest management[30]. This regulation effort was aided by a new posture to Nature as an outside entity to human societies and the rise of nationalism in Europe[31].

The invasion of Switzerland by the French revolutionary army in 1795 would mark the transition from the Old Swiss Confederation to the Modern Confederation of 1848, with transitional regimes that are the Helvetian Republic (1798-1803), the Swiss Confederation (1803-1814) and the Restored Confederation (1815-1848). The French invasion left a political legacy anchored in liberalism, partly restrained by the restoration of the Old Regime after the Congress of Vienna (1815)[32]. Among others, a significant change in the political realm was the abrogation of seignorial rights and their subsequent privileges, such as hunting. Hence, hunting became an activity that could be practiced by anyone in the civil population. Concerning forests, the Helvetic Republic transferred the management of forests to the Bourgeoisie or the sum of possessors of right of citizenship in one community. From seigneurial hands, the property was spread into different private hands[33].

The shift in legislation and a greater push for natural resources led to the consequences we mentioned before, with the depletion of a major part of the forest ecosystems of the territory and the fauna that came with it. Given the gravity of the situation in the 1870’s, a federal law was passed for the protection of forests, birds and game in 1875. The law limited the hunting season to 14 days per year and applied to certain categories of animals. A mother and their cubs were protected by this law, unlike the predators who were considered disposable. The main promoter of the law on hunting and forests was Johann Coaz (1822-1918)[34], the first federal inspector of forests from 1875 to 1914. Before that, he served in different state services before becoming inspector for the cantons of Saint-Gall and Graubünden. He assumed this government key-posts until the end of his life in the 1910’s.

The invasion of Switzerland by the French revolutionary army in 1795 would mark the transition from the Old Swiss Confederation to the Modern Confederation of 1848, with transitional regimes that are the Helvetian Republic (1798-1803), the Swiss Confederation (1803-1814) and the Restored Confederation (1815-1848). The French invasion left a political legacy anchored in liberalism, partly restrained by the restoration of the Old Regime after the Congress of Vienna (1815)[32]. Among others, a significant change in the political realm was the abrogation of seignorial rights and their subsequent privileges, such as hunting. Hence, hunting became an activity that could be practiced by anyone in the civil population. Concerning forests, the Helvetic Republic transferred the management of forests to the Bourgeoisie or the sum of possessors of right of citizenship in one community. From seigneurial hands, the property was spread into different private hands[33].

The shift in legislation and a greater push for natural resources led to the consequences we mentioned before, with the depletion of a major part of the forest ecosystems of the territory and the fauna that came with it. Given the gravity of the situation in the 1870’s, a federal law was passed for the protection of forests, birds and game in 1875. The law limited the hunting season to 14 days per year and applied to certain categories of animals. A mother and their cubs were protected by this law, unlike the predators who were considered disposable. The main promoter of the law on hunting and forests was Johann Coaz (1822-1918)[34], the first federal inspector of forests from 1875 to 1914. Before that, he served in different state services before becoming inspector for the cantons of Saint-Gall and Graubünden. He assumed this government key-posts until the end of his life in the 1910’s.

[Picture 8] Photograph of a mountainside in canton Schwyz, 1918, Gelatin-negative photograph, W. Keller, Zürich, LM-91088.2, credits: Swiss National Museum, consulted on 02.04.22.

[35] Georg Kreis: "Nation", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version of 26.04.2011, translated from German. Online reference >>, consulted on 15.04.2022.

Culturally and ideologically speaking, the creation of a national identity in Switzerland was a significant element in the first steps for the protection of the forest ecosystem. The construction of a common identity wasn't evidence for Switzerland, and it was one of the great works of the 19th century for the federal government. Until the turning point of 1848, each canton was considered as a highly autonomous political entity, having each its own currency and borders. The element found as a unity tool was the concept of Heimat. The notion of Heimat could be translated by “home” or “fatherland”, it engulfed the space containing the essence of the Swiss nation and by extension its people[35]. The national spirit found its strongest expression in the landscapes of the Alps, because it was thought at this period that it was constitutive of the Swiss identity.

[Picture 9] “To shoot down protected animals? Hunting Act. No! The 27th September 2020”, poster for the referendum on the Hunting Act for the No by the Green Party, 2020, @Les Verts, consulted the 02.04.22. Nowadays, the tension on the regulation of hunting is still a heated topic in recent votations.

[36] Walter, Catastrophes, part II.

[37] Stefan Bachmann: "Heimatschutz", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version of 18.04.2012, translated from German. Online reference >>, consulted on 15.04.2022

[38] Kupper, Creating Wilderness.

[39] For further information about the genetic makeup and the health of current population: Online reference >>.

[40] Online reference >>, 2005.

[41] Federal Council, The lynx, 2016, Online reference >> (page suppressed).

[42] Walter Thut: "Marais", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version of 22.10.2019, translated from German. Online reference >>, consulted on 15.04.2022.

[43] Jörg Schibler, Peter Lüps; Jörg Schibler; Peter Lüps: "Faune", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version of 23.10.2006, translated from German. Online reference >>, consulted on the 15.04.2022.

[44] Angelus Eisinger: "Urbanisation", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version of 22.01.2015, translated from German. Online reference >>, consulté le 15.04.2022

Mountains, with this process, underwent a fascinating evolution in mentalities, from a dangerous and hostile place to a central piece in the national feeling. Thanks partly to romantism, the notion of sublime or one’s feeling of smallness toward the overwhelming power of Nature progressively spread to all layers of the population[36]. The revolution of transports and the intensification of pastoral agriculture in those regions helped the local population to grow confident in its capacity to handle that environment. In other words, the mountains seemed less terrifying as they used to.

In addition to ideological reasons, the use of the Alps as a factor of nationalism was a sensible choice since most of the origins of Switzerland (in the fashion of the romanticized version) took place in the region and covered most of the national territory. Patrimonial reasons to embryony steps in environmentalism in the country. Since the forest and the mountainous milieu were sacralized, a part of the population had a heightened sensibility to a sense of loss, mostly the product of the Swiss society’s profound transformations. In the end of the 19th century, the concept of Heimatschutz, protection of the heritage, emerged in reaction to the fast pace of construction of infrastructures for tourism or transport[37]. Denaturing the Alps equaled somehow to alter the national identity. This opposition trend concerned as much the culture as the natural sphere: the Swiss Heritage Society and the Swiss League for the Protection of Nature were established in 1905 and 1909 respectively. Joining the global trend of the sanctuarization of Nature, the Swiss Natural Parc was founded in 1914[38].

It is a recurring misconception to assert that the wolf or other great predators were completely extinct on Swiss territory for more than a hundred years. Wolf and bears made several appearances in the local newspapers during the last thirty years before their reintroduction or stronger presence in more recent years. Where did this misunderstanding come from? The most solid explanation could be that it was an extrapolation from a certain truth. The fact is that most of the former populations of great predators dwindled to a bottleneck state, to the point where it could sustain itself without genetic material from neighboring populations[39]. For example, the Alpine population of bears living in Switzerland was seemingly hunted to extinction, but some individuals coming from the Dinaric Alps and Apennines in Italy migrated sporadically or are seemingly to migrate in Switzerland, if not reintroduced from other populations[40]. The other hypothesis is that the traces didn’t suffice to be considered substantial by observers or to sustain a perennial population.

The first step to the repopulation of Switzerland by the super-predators was taken during in 1971 with the return of the lynx was noticed by the Ministry of the Environment[41]. The reintroduction of that species was followed by others such as the bearded vultures in 1991, when the first couple was released in the National Swiss Park (1991-2007). The preconditions for the reintroduction or the natural return of the wolf and the brown bear took shape all along the 20th century. The 20th century was characterized by paradoxical trends concerning the environment. On one hand, the forest biome as well as its inhabitants recovered due to the measures taken by the federal government about hunting and felling; on the other hand, the intensification of the agriculture, plus the drying of humid areas on the Plateau led to dramatic damages to the concerned species. The great loss of wetlands and prairies can be explained using pesticides and fertilizers during the Postwar period, to increase the productivity of agriculture at great costs[42]. The expansion of croplands added to the correction of rivers led to a drying out of these same wetlands. Same wise, the prairies, considered as unused lands, were seen as non-productive, they were consequently “put to use”. It is still an ongoing crisis and even common animals, like brown hares (Lepus europeanus) are now threatened by habitat loss. The relative regrowth of forests resulted from a mix from natural regrowth and campaigns of reforestation done by various actors, among them the federal government.

Beyond the effects of policies, we ought to mention anthropological factors. The evolution of mentalities, especially after the World War II and with the rise of environmentalism in some layers of the civil society. We observe that to some extent, the cultural perception populations had towards animals considered as “nefarious” reversed. A better understanding of the ecological value of these species and their capital ecological role could explain partly the reversal of point of view concerning the wolf or bears[43]. Socioeconomic factors, such as the decline of pastoralism as mean of survival and the significant increase of the wealth per capita, explained the fact those predators wouldn’t perceived as threats anymore. A better understanding of nature and the will to protect the environment could link, to some extent, to a feeling of nostalgia of the population towards nature. The rapid increase of the population and a sprawling urbanization during the Postwar growth period took a serious toll to the environment, with visible scars[44]. The very observations of such degradations or changes sparked the conscience of the necessity of protecting what was left. The situation similar to the biodiversity crisis of the 19th century repeated, on a much larger scale and as a global movement.

In addition to ideological reasons, the use of the Alps as a factor of nationalism was a sensible choice since most of the origins of Switzerland (in the fashion of the romanticized version) took place in the region and covered most of the national territory. Patrimonial reasons to embryony steps in environmentalism in the country. Since the forest and the mountainous milieu were sacralized, a part of the population had a heightened sensibility to a sense of loss, mostly the product of the Swiss society’s profound transformations. In the end of the 19th century, the concept of Heimatschutz, protection of the heritage, emerged in reaction to the fast pace of construction of infrastructures for tourism or transport[37]. Denaturing the Alps equaled somehow to alter the national identity. This opposition trend concerned as much the culture as the natural sphere: the Swiss Heritage Society and the Swiss League for the Protection of Nature were established in 1905 and 1909 respectively. Joining the global trend of the sanctuarization of Nature, the Swiss Natural Parc was founded in 1914[38].

It is a recurring misconception to assert that the wolf or other great predators were completely extinct on Swiss territory for more than a hundred years. Wolf and bears made several appearances in the local newspapers during the last thirty years before their reintroduction or stronger presence in more recent years. Where did this misunderstanding come from? The most solid explanation could be that it was an extrapolation from a certain truth. The fact is that most of the former populations of great predators dwindled to a bottleneck state, to the point where it could sustain itself without genetic material from neighboring populations[39]. For example, the Alpine population of bears living in Switzerland was seemingly hunted to extinction, but some individuals coming from the Dinaric Alps and Apennines in Italy migrated sporadically or are seemingly to migrate in Switzerland, if not reintroduced from other populations[40]. The other hypothesis is that the traces didn’t suffice to be considered substantial by observers or to sustain a perennial population.

The first step to the repopulation of Switzerland by the super-predators was taken during in 1971 with the return of the lynx was noticed by the Ministry of the Environment[41]. The reintroduction of that species was followed by others such as the bearded vultures in 1991, when the first couple was released in the National Swiss Park (1991-2007). The preconditions for the reintroduction or the natural return of the wolf and the brown bear took shape all along the 20th century. The 20th century was characterized by paradoxical trends concerning the environment. On one hand, the forest biome as well as its inhabitants recovered due to the measures taken by the federal government about hunting and felling; on the other hand, the intensification of the agriculture, plus the drying of humid areas on the Plateau led to dramatic damages to the concerned species. The great loss of wetlands and prairies can be explained using pesticides and fertilizers during the Postwar period, to increase the productivity of agriculture at great costs[42]. The expansion of croplands added to the correction of rivers led to a drying out of these same wetlands. Same wise, the prairies, considered as unused lands, were seen as non-productive, they were consequently “put to use”. It is still an ongoing crisis and even common animals, like brown hares (Lepus europeanus) are now threatened by habitat loss. The relative regrowth of forests resulted from a mix from natural regrowth and campaigns of reforestation done by various actors, among them the federal government.

Beyond the effects of policies, we ought to mention anthropological factors. The evolution of mentalities, especially after the World War II and with the rise of environmentalism in some layers of the civil society. We observe that to some extent, the cultural perception populations had towards animals considered as “nefarious” reversed. A better understanding of the ecological value of these species and their capital ecological role could explain partly the reversal of point of view concerning the wolf or bears[43]. Socioeconomic factors, such as the decline of pastoralism as mean of survival and the significant increase of the wealth per capita, explained the fact those predators wouldn’t perceived as threats anymore. A better understanding of nature and the will to protect the environment could link, to some extent, to a feeling of nostalgia of the population towards nature. The rapid increase of the population and a sprawling urbanization during the Postwar growth period took a serious toll to the environment, with visible scars[44]. The very observations of such degradations or changes sparked the conscience of the necessity of protecting what was left. The situation similar to the biodiversity crisis of the 19th century repeated, on a much larger scale and as a global movement.

[Picture 10] Map of the current distribution of wolves in Switzerland, since 2012. Datas and map by cantons and kora, in: Le loup en Suisse (The wolf in Switzerland), 2020, Online reference >>, consulted on the 15.04.22.

[45] ATS, « Animal féroce à abattre » (Ferocious Animal to Slay), in: L’Express, 18.08.1995

[46] Ainhoa Ibarrola, « Faut-il protéger les grands prédateurs ou s’en méfier ? La question qui divise en Suisse. » (Do we have to protect the great predators or distrust them ? The question that divides in Switzerland.), July 2020,Online reference >>, consulted 22.03.22.

However, the current situation since 1995 and the case of the “Beast of Val Ferret” compels us to think with more accuracy with the complicated relationship the Swiss population has with the great predators[45]. Despite a general positive attitude towards the predators, especially the wolf, peculiar layers of the population welcomed this stronger return of the former apex predator with hostility. The social circles showing a hostile point of view seem mostly to be inhabitants of the Alpine regions, the heartland of the lupine presence on the Swiss territory. The most vocal detractors can be found amongst Alpine farmers, raising majorly cattle and sheep. We may add the communities not working in primary sector but living in the same mountainous areas. Every territory being outside of the Plateau and densely populated areas tend to live in closer contact with super-predators, this circumstance leads to tensions. The frontier between confrontation and cohabitation becomes slim and will depend mainly on the socioeconomic factors, on the behavior of animals, on the quality of the habitat; for short on the margin of tolerance let by human communities for the fauna. The margin varies widely depending on the status of the animal, the bearded vulture or the lynx being a peripheric source of concern for the agricultural circles of the country.

The interesting side of the current debate is to observe the resurgence of the older reflexes about the super-predators, mostly the wolf and the bear. We can observe a durable fear expressed by local populations in the proximity of animals, recalling centuries-old cultural representations. Does the actual daily proximity with the concerned species keep more ancient representations alive? It seems that several historical layers of interaction are coexisting within the Swiss society, creating a schizophrenic situation which in fact contain clear divides, geographical divides. The bigger picture allows us, nevertheless, to consider that the most recent layer has a more significant impact: most of the Swiss population sees their presence positively, aware of their ecological importance and by a recent kind of sensitivity[46]. This consensus would benefit to the great predators, especially the wolf, on the national level, seeking to protect them and to manage financially the damages they could provoke. The regional and local levels are more complicated since the tensions are more acute. Given a stronger lupine population for the coming years, we could expect tensions to worsen to an unknown extent. The outcome will depend on how the civil debate tackle the problem, namely the elimination of the perturbator or the creation of the durable conditions for cohabitation.

The interesting side of the current debate is to observe the resurgence of the older reflexes about the super-predators, mostly the wolf and the bear. We can observe a durable fear expressed by local populations in the proximity of animals, recalling centuries-old cultural representations. Does the actual daily proximity with the concerned species keep more ancient representations alive? It seems that several historical layers of interaction are coexisting within the Swiss society, creating a schizophrenic situation which in fact contain clear divides, geographical divides. The bigger picture allows us, nevertheless, to consider that the most recent layer has a more significant impact: most of the Swiss population sees their presence positively, aware of their ecological importance and by a recent kind of sensitivity[46]. This consensus would benefit to the great predators, especially the wolf, on the national level, seeking to protect them and to manage financially the damages they could provoke. The regional and local levels are more complicated since the tensions are more acute. Given a stronger lupine population for the coming years, we could expect tensions to worsen to an unknown extent. The outcome will depend on how the civil debate tackle the problem, namely the elimination of the perturbator or the creation of the durable conditions for cohabitation.

Conclusion

After having seen in this short essay the tumultuous relationship of the five last centuries between the great predators on the Swiss territory and its human population. In the long duration, we could see that the species of great predators were exterminated progressively, culminating during the 19th century with the forest biodiversity crisis. We could moreover consider the extinction of superpredators as only one aspect of a larger crisis that led to the full depletion of one ecosystem. Nevertheless, the image could be reversed: the climax of that century was prepared by a decline of population due to the factors we have seen in the first chapter. The most prevalent factors included: the amelioration and the democratization of firearms in the civil population during the 18th and the negative cultural reception of the superpredators. The third act of this history was marked by the return or the reintroduction of the animal of prey in Switzerland. We could interpret this return as a period of recovery of the sylvan ecosystem and the restoration of the living conditions of the predators.

Besides the role of the State in the recovery, one remarks the resiliency of these species and by its relatively rapid pace of recovery given the time of its decline, almost three centuries. Even though the first cycle of the biodiversity crisis was complete, the threat of climate change and the second episode of the biodiversity crisis would surely destabilize the fragile progress that was made at the end of the 20th century. The rising temperatures in the forest will destabilize the ecosystems and disturb the natural behavior of the predators. Nevertheless, the future of superpredators in the Swiss territory seems still fragile but stable. Two factors argue in favor of this proposition: the continuation of the conditions necessary to the predators and the partial shift in the representation of predatory species from negative to positive. This relationship to come won’t happen without tensions, where the Federal State will have a determinant role in the resolution of these tensions.

For future researches, the principal boulevard could be to consider in the larger scope the cycle of biodiversity crisis on the global stage and the relationship with the evolution of human societies.

Besides the role of the State in the recovery, one remarks the resiliency of these species and by its relatively rapid pace of recovery given the time of its decline, almost three centuries. Even though the first cycle of the biodiversity crisis was complete, the threat of climate change and the second episode of the biodiversity crisis would surely destabilize the fragile progress that was made at the end of the 20th century. The rising temperatures in the forest will destabilize the ecosystems and disturb the natural behavior of the predators. Nevertheless, the future of superpredators in the Swiss territory seems still fragile but stable. Two factors argue in favor of this proposition: the continuation of the conditions necessary to the predators and the partial shift in the representation of predatory species from negative to positive. This relationship to come won’t happen without tensions, where the Federal State will have a determinant role in the resolution of these tensions.

For future researches, the principal boulevard could be to consider in the larger scope the cycle of biodiversity crisis on the global stage and the relationship with the evolution of human societies.

Bibliography

Agnoletti, Mauro, and Simone Neri Serneri, eds. The Basic Environmental History. 1st ed. 2014. Environmental History 4. Cham: Springer International Publishing : Imprint: Springer, 2014. Reference >>

Byrne, Joseph Patrick. Encyclopedia of the Black Death. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, 2012.

Crosby, Alfred W. The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. 30th anniversary ed. Westport, Conn: Praeger, 2003.

Kupper, Patrick. Creating Wilderness: A Transnational History of the Swiss National Park. English language edition. The Environment in History : International Perspectives, volume 4. New York: Berghahn, 2014.

Leeuw, Sander van der. Social Sustainability, Past and Future: Undoing Unintended Consequences for the Earth’s Survival. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press, 2019. Reference >>

Mathieu, Jon. History of the Alps, 1500-1900: Environment, Development, and Society. 1st English ed. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2009.

Perrot, Xavier. “Passions cynégénétiques. Anthropologie historique du droit de la chasse au grand gibier en France.” Revue semestrielle de droit animalier, Observatoire des mutations institutionnelles et juridiques, UNiversité de Limoges, Vol. 1 (2015): p.329-361.

Thiesse, Anne-Marie. La Création Des Identités Nationales: Europe, XVIIIe-XXe Siècle. L’univers Historique. Paris: Seuil, 1999.

Walter, François. Catastrophes : une histoire culturelle : XVIe-XXIe siècle. L’Univers historique. Paris: Ed. du Seuil, 2008. Reference >>.

Une histoire de la Suisse. Neuchâtel [Charenton-le-Pont]: Éditions Alphil-Presses universitaires suisses [FMSH diffusion], 2016.Reference >>, 2005.

Byrne, Joseph Patrick. Encyclopedia of the Black Death. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, 2012.

Crosby, Alfred W. The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. 30th anniversary ed. Westport, Conn: Praeger, 2003.

Kupper, Patrick. Creating Wilderness: A Transnational History of the Swiss National Park. English language edition. The Environment in History : International Perspectives, volume 4. New York: Berghahn, 2014.

Leeuw, Sander van der. Social Sustainability, Past and Future: Undoing Unintended Consequences for the Earth’s Survival. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press, 2019. Reference >>

Mathieu, Jon. History of the Alps, 1500-1900: Environment, Development, and Society. 1st English ed. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2009.

Perrot, Xavier. “Passions cynégénétiques. Anthropologie historique du droit de la chasse au grand gibier en France.” Revue semestrielle de droit animalier, Observatoire des mutations institutionnelles et juridiques, UNiversité de Limoges, Vol. 1 (2015): p.329-361.

Thiesse, Anne-Marie. La Création Des Identités Nationales: Europe, XVIIIe-XXe Siècle. L’univers Historique. Paris: Seuil, 1999.

Walter, François. Catastrophes : une histoire culturelle : XVIe-XXIe siècle. L’Univers historique. Paris: Ed. du Seuil, 2008. Reference >>.

Une histoire de la Suisse. Neuchâtel [Charenton-le-Pont]: Éditions Alphil-Presses universitaires suisses [FMSH diffusion], 2016.Reference >>, 2005.