Apis mellifera in history, part 1

Published:: 2023-05-01

Author:: William Favre

Topics:: [Environment] [Science] [Animals]

Related articles::

[The arrival of Apis mellifera to Japan, part 2]

[The arrival of Apis mellifera to Japan, part 2]

The rise of modern beekeeping

The goal of this article is to uncover the history of beekeeping in Japan in a series of several parts. We will explore how Western (Euro-American) beekeeping entered Japan and how the introduction of the species Apis mellifera revealed itself to be difficult in this new ecosystem for this species.

A broader two-part series will study the environmental history of beekeeping in Japan and the Western World, more particularly on how the two regions intertwine in a certain array, thus impacting the art of beekeeping in both regions, over the span of almost two centuries. We will look especially at the last five centuries, with the rise of naturalism and modern enthomology and changed the way we considered bees.

Introducing Apis mellifera and its history

Apis mellifera is the taxonomic name given to honeybees that we find the most on the globe in geographical terms. However, various varieties found under the name of apis mellifera are a very small fraction of the bee species we can find on Earth. We can count around 20’000 species of bees in total. The bees are included in the superfamily of Apoidea, regrouping the families of wasps and hornets. The broader taxonomic group is the order of Hymenoptera, which regroups ants and white ants among others. This order is mainly characterized by the presence of hooks connecting the hindwings to the forewings and counts approximately 200’000 species around the world.

This taxonomic group appeared 200 million years ago during the Jurassic period. However, the function of pollinators typically associated with bees occurred about a hundred million years later during the Cretaceous period with the apparition of flowering plants, creating a new type of relationship between plants and insect species that took the newly opened ecological niche. We find bee species all around the globe, excluding Antarctica and the polar regions around the Arctic. Among this vast diversity of species spanning on five continents. We can observe a variety of behavior that contrasts with the common image of honeybees. The two other behavior patterns observed in bee species are parasitic and solitary, both being non exclusive to each other. Being social and living in hives is the common trait we find in all domesticated species of honeybees. The explanation behind is the fact that the domestication of bees is linked to the historical conditions spanning back to the Neolithic. Besides historical reasons. The selection of the social characteristic is motivated by advantages like protection against predators or the collectivisation of different tasks among the colony. The main advantage brought by social behavior is the repartition of the energy and time of a single individual per task. This strategy lowers as well the odd a significant part of the hive behind lost or eaten, since the most experimented worker bees are venturing outside to collect food. It allows a better chance of survival since a swath of the colony will take care of the offspring, hence the future of the colony. One shouldn’t forget, however, that the evolutionary trajectory of social bee species is the result of a certain context spanning over millions of years. It is then impossible to judge that a behavior pattern is better than another but fitter than the other in a particular context.

The encounter of human beings and honeybees has been prepared priorly by the migratory pattern of each species. The last Ice Age (115’000 to 11’700 years before the present) shaped the living areas of each species, expanding northwards when the climate heated up after the last glacial maximum. Apis mellifera, originating in sub-Saharan Africa, colonized progressively North Africa and Europe, crossing over by the Middle East. Homo sapiens frequented the same routes to exit Africa to Eurasia. The overlapping of these two species over a long period of time, under the same climatic conditions, probably helped the shift from predation to domestication. Agriculture would have been a response to the rarefaction of resources due to an aridification of the local climate in the Fertile Crescent.

In short, the overall trajectory of the relationship between humans and bees transitioned from predation to dependency to a certain degree, given the current agricultural context. The turning point in the history of the relationship between humans and apis genre species was domestication that was a direct consequence of the Neolithic Revolution, which happened in different parts of the world independently or through diffusion of this new lifestyle.

This taxonomic group appeared 200 million years ago during the Jurassic period. However, the function of pollinators typically associated with bees occurred about a hundred million years later during the Cretaceous period with the apparition of flowering plants, creating a new type of relationship between plants and insect species that took the newly opened ecological niche. We find bee species all around the globe, excluding Antarctica and the polar regions around the Arctic. Among this vast diversity of species spanning on five continents. We can observe a variety of behavior that contrasts with the common image of honeybees. The two other behavior patterns observed in bee species are parasitic and solitary, both being non exclusive to each other. Being social and living in hives is the common trait we find in all domesticated species of honeybees. The explanation behind is the fact that the domestication of bees is linked to the historical conditions spanning back to the Neolithic. Besides historical reasons. The selection of the social characteristic is motivated by advantages like protection against predators or the collectivisation of different tasks among the colony. The main advantage brought by social behavior is the repartition of the energy and time of a single individual per task. This strategy lowers as well the odd a significant part of the hive behind lost or eaten, since the most experimented worker bees are venturing outside to collect food. It allows a better chance of survival since a swath of the colony will take care of the offspring, hence the future of the colony. One shouldn’t forget, however, that the evolutionary trajectory of social bee species is the result of a certain context spanning over millions of years. It is then impossible to judge that a behavior pattern is better than another but fitter than the other in a particular context.

The encounter of human beings and honeybees has been prepared priorly by the migratory pattern of each species. The last Ice Age (115’000 to 11’700 years before the present) shaped the living areas of each species, expanding northwards when the climate heated up after the last glacial maximum. Apis mellifera, originating in sub-Saharan Africa, colonized progressively North Africa and Europe, crossing over by the Middle East. Homo sapiens frequented the same routes to exit Africa to Eurasia. The overlapping of these two species over a long period of time, under the same climatic conditions, probably helped the shift from predation to domestication. Agriculture would have been a response to the rarefaction of resources due to an aridification of the local climate in the Fertile Crescent.

In short, the overall trajectory of the relationship between humans and bees transitioned from predation to dependency to a certain degree, given the current agricultural context. The turning point in the history of the relationship between humans and apis genre species was domestication that was a direct consequence of the Neolithic Revolution, which happened in different parts of the world independently or through diffusion of this new lifestyle.

Mesolithic rock painting of a honey hunter harvesting honey and wax from a bees nest in a tree. At Cuevas de la Araña en Bicorp. (Dating around 8000 to 6000 BC), Spain, Link to original image, consulted 5/12/2021.

Mellivora capensis (Honey Badger) in Howletts Wild Animal Park, Kent, England, CT Cooper, 2011, Link to original picture, consulted 2021.

Before the Neolithic, human beings were already interacting with bees based on a hunter-gatherer-collector lifestyle by paleolithic and mesolithic human groups. Bees, especially combs containing honey, were particularly valued by collectors who sought this product as an important source of nutrients and calories. Diet-wise, honey contains glucids and a wide range of proteins in sparse amounts with antiseptic properties, explaining why humans hunted beehives despite the hustle of bringing the nests down and the threat of bee stings. Parietal paintings are depicting such scenes where a team of collectors shared the tasks of taking the combs away while a second took the precious honey into a proper container. However, humans aren’t the only species predating bees for their honey. Beside the well-known case of bears, we may cite indicator birds (Indicatoridae) or honey badgers (Mellivora capensis) being species consuming honey for the same reasons as humans.

Greater honeyguide, Gambia (Indicator indicator), gisela gerson lohman-braun, 2013, Link to original picture , consulted on 5/12/2021.

The end of the last glacial maximum around 10’000 BC and the heating up of the climate marked the beginning of a new phase in the human-bee relation, as mentioned earlier. The story of the domestication of one animal or vegetal species somehow follows a parallel pattern. But we can notice in the case of bees an interesting twist: the domestication of multiple local bee species by a recently sedentary population after an accidental accounter, leading to a tradition of beekeeping in various corners of the world.

Sedentarization, as researchers like Andrew Scott put it, was an adaptive response of communities to a plentiful environment or oppositely to concentrate themselves in denser communities located in oases of abundant resources when the surroundings environmental conditions worsened. The rarefaction of plant or animal life in the region of the Fertile Crescent during an episode of warming up led to a shift in the local environment for a dryer and or a landscape marked by a diminished array of collectible plants by gatherers-collectors. In this perspective of a shrinking and uncertain food supply, domestication and the beginnings of agriculture would have been a tool for the first farmer communities to maintain a steady and abundant food supply. Agriculture, in the case of swidden agriculture or flooded land agriculture, represents a means among others of landscape architecture. Observing it sufficed to spread seeds or to plant them, with few weeds on these fields, a keen eye would understand the interest of the gain and effort it represented.

However, the seemingly abundance of food and stocks brought by an agropastoral lifestyle comes with a price. The adoption of such living provoked a degradation of the overall conditions of this farming humanity and the emergence of social stratification as consequence. Agriculture provoked a significant increase in the work needed to obtain the same amount of food compared to a more nomadic lifestyle, without mentioning the toil it represented. The dietary balance and caloric income was affected by the diminution of the average height and a shortening of the average lifespan. Worse, the rise of agriculture marked the beginning of the age of zoonosis and hunger. The close proximity of farmers and livestock in the same environment, the household was the perfect milieu to spread diseases from the animal population to humans (a tendency which is confirmed once more in recent times). Plus the dependency of entire sedentary populations on a few vegetal and animal species concentrated in a specific place, a field or a stable would create a fragility to everything affecting the stocks on which the communities depended. A year of bad weather or a wave of pests would threaten the existence of the community if they didn't have a backup strategy.

In this regard, beekeeping was born in this context of shifting in specific regions of the planet from the relationship between human and other species, and its environment in a broader sense. Based on the work of the archeologist Jean Cauvin for example, the regions concerned by the emergence of agriculture developed progressively a different conceptualization of their environment in contrast to their counterparts. The apparition of anthropomorphic figures considered as gods or divinities is theorized as the apparition of a more anthropocentric view of the world. Scott’s opinion is that settlement triggered profound changes to the social fabric of humanity and significantly reduced its ritual life.

In this larger narrative, the adoption of bees in the bestiary of domesticated species is the result of an accident, it seems. Bee colonies had the habit to dwell in cavities and protected areas, away from dangers such as predators, rain and wind. Items like empty baskets or pots became the first and accidental beehive of history. Noting the potential of the artificial beehives, Neolithic farmers reproduced the maneuver intentionally and reinforced the bond between both species because the relationship seemed more mutual than plain predation. Humans favored the reproductive success of Apis mellifera and its cousin species by giving shelter and food in form of fields or orchards and honeybees pollinated in return the vegetal species while furnishing honey, propolis and beeswax.

From that point, we can see various traditions of beekeeping birthing all corners of the globe, with the most ancient archeological evidence coming from the Fertile Crescent, in sites in the Levant and Egypt. Moreover, bees and honey came to take an important place in human minds. Bees and honey came to be considered as symbols of plenty and fertility or industriousness in various societies, ranging from Central America to Asia, while stopping in Africa. In mythologies across the world, honey and bees endorse the function of symbols of values such prosperity, wealth and fertility. In Ancient Egypt, honey was considered the tears of the hawk god, Horus; whereas it is mentioned as an epitome of prosperity in the Ancient Testament. However, the animal symbolism of bees evolves over time as the social context alters.

Sedentarization, as researchers like Andrew Scott put it, was an adaptive response of communities to a plentiful environment or oppositely to concentrate themselves in denser communities located in oases of abundant resources when the surroundings environmental conditions worsened. The rarefaction of plant or animal life in the region of the Fertile Crescent during an episode of warming up led to a shift in the local environment for a dryer and or a landscape marked by a diminished array of collectible plants by gatherers-collectors. In this perspective of a shrinking and uncertain food supply, domestication and the beginnings of agriculture would have been a tool for the first farmer communities to maintain a steady and abundant food supply. Agriculture, in the case of swidden agriculture or flooded land agriculture, represents a means among others of landscape architecture. Observing it sufficed to spread seeds or to plant them, with few weeds on these fields, a keen eye would understand the interest of the gain and effort it represented.

However, the seemingly abundance of food and stocks brought by an agropastoral lifestyle comes with a price. The adoption of such living provoked a degradation of the overall conditions of this farming humanity and the emergence of social stratification as consequence. Agriculture provoked a significant increase in the work needed to obtain the same amount of food compared to a more nomadic lifestyle, without mentioning the toil it represented. The dietary balance and caloric income was affected by the diminution of the average height and a shortening of the average lifespan. Worse, the rise of agriculture marked the beginning of the age of zoonosis and hunger. The close proximity of farmers and livestock in the same environment, the household was the perfect milieu to spread diseases from the animal population to humans (a tendency which is confirmed once more in recent times). Plus the dependency of entire sedentary populations on a few vegetal and animal species concentrated in a specific place, a field or a stable would create a fragility to everything affecting the stocks on which the communities depended. A year of bad weather or a wave of pests would threaten the existence of the community if they didn't have a backup strategy.

In this regard, beekeeping was born in this context of shifting in specific regions of the planet from the relationship between human and other species, and its environment in a broader sense. Based on the work of the archeologist Jean Cauvin for example, the regions concerned by the emergence of agriculture developed progressively a different conceptualization of their environment in contrast to their counterparts. The apparition of anthropomorphic figures considered as gods or divinities is theorized as the apparition of a more anthropocentric view of the world. Scott’s opinion is that settlement triggered profound changes to the social fabric of humanity and significantly reduced its ritual life.

In this larger narrative, the adoption of bees in the bestiary of domesticated species is the result of an accident, it seems. Bee colonies had the habit to dwell in cavities and protected areas, away from dangers such as predators, rain and wind. Items like empty baskets or pots became the first and accidental beehive of history. Noting the potential of the artificial beehives, Neolithic farmers reproduced the maneuver intentionally and reinforced the bond between both species because the relationship seemed more mutual than plain predation. Humans favored the reproductive success of Apis mellifera and its cousin species by giving shelter and food in form of fields or orchards and honeybees pollinated in return the vegetal species while furnishing honey, propolis and beeswax.

From that point, we can see various traditions of beekeeping birthing all corners of the globe, with the most ancient archeological evidence coming from the Fertile Crescent, in sites in the Levant and Egypt. Moreover, bees and honey came to take an important place in human minds. Bees and honey came to be considered as symbols of plenty and fertility or industriousness in various societies, ranging from Central America to Asia, while stopping in Africa. In mythologies across the world, honey and bees endorse the function of symbols of values such prosperity, wealth and fertility. In Ancient Egypt, honey was considered the tears of the hawk god, Horus; whereas it is mentioned as an epitome of prosperity in the Ancient Testament. However, the animal symbolism of bees evolves over time as the social context alters.

Historiography, a concise survey

The history of beekeeping has developed from three spheres of expertise: the professionals of beekeeping, specialists of entomology and social scientists. The blend of technicians, biologists and social scientists on the other side led to a very interesting development about the relationship between honeybees and humans. The literature about beekeeping is diversified and we ought to narrow the survey to the historiography of beekeeping.

In this regard, Eva Crane is among one of the best-known personalities of the field. She represents well the part of non-historians who turned their interest to beekeeping out of passion, since Crane majored in physics beforehand. Her work on the world history of beekeeping is among the most significant contributions to the field. Even if she hasn’t a historian educational background, her expertise cannot be denied. The approach taken by Eva Crane emphasizes on the complexity and the diversity of the link connecting both species, adding to the mixture the thickness of a chronological perspective. The downside of Crane’s work comes from the scale she adopts in her books, which is more a global survey of the beekeeping world than a deep inspection of a region in particular. Nonetheless, the non-historical background of hers brings a refreshing insight of such a subject.

The research of Eva E. Crane is not the only researcher worth noting. Gene Kritsky, David Pattinson or the magazine Bee culture. In the case of these authors, the stake is opposite to Crane because the region of appraisal is much more restrained, looking at the art of beekeeping through the lens of a given space and time, or angle. The interesting thing is the use of national context as a mean of scrutiny. The advantage of the national scale is to cover a well delimited territory and to appreciate already the regional differences of beekeeping inside a same ensemble. The practicality of the national ladder set aside, to consider the national scale as a main framework brings different biases. It tends to marginalize the exchanges or the circulations transcending national borders and can be quite artificial in regard to certain geographical contexts. The global dimension of beekeeping, especially of Apis mellifera is better considered by Jean-Paul Burdy and the blog “la République des abeilles [the bee Republic]”, where this project of global circulation is at its heart.

It is interesting to note as well that much of the regions covered by the history of beekeeping is Euro-America or China. The other bias is seen to concentrate majorly on one species, Apis mellifera and the story of its dissemination throughout much of the world by different routes, mostly following the path of European colonization at the end of the Middle Ages (15th century). The issue with such a perspective has been to overshadow the history of other traditions worldwide or the interaction of human societies with the rest of the Apis genre. Moreover, the relation between bee species has been, it seems, overlooked even though the arrival of the Apis mellifera and its varieties encountered many local counterparts when the Europeans arrived to control large swaths of the Americas, Asia, Africa and Oceania. It is important in this instance to underline the tension put by the arrival of not only a competitor species but socio-technical system surrounding the bees, putting the traditional beekeeping styles in competition and under pressure.

In this regard, Eva Crane is among one of the best-known personalities of the field. She represents well the part of non-historians who turned their interest to beekeeping out of passion, since Crane majored in physics beforehand. Her work on the world history of beekeeping is among the most significant contributions to the field. Even if she hasn’t a historian educational background, her expertise cannot be denied. The approach taken by Eva Crane emphasizes on the complexity and the diversity of the link connecting both species, adding to the mixture the thickness of a chronological perspective. The downside of Crane’s work comes from the scale she adopts in her books, which is more a global survey of the beekeeping world than a deep inspection of a region in particular. Nonetheless, the non-historical background of hers brings a refreshing insight of such a subject.

The research of Eva E. Crane is not the only researcher worth noting. Gene Kritsky, David Pattinson or the magazine Bee culture. In the case of these authors, the stake is opposite to Crane because the region of appraisal is much more restrained, looking at the art of beekeeping through the lens of a given space and time, or angle. The interesting thing is the use of national context as a mean of scrutiny. The advantage of the national scale is to cover a well delimited territory and to appreciate already the regional differences of beekeeping inside a same ensemble. The practicality of the national ladder set aside, to consider the national scale as a main framework brings different biases. It tends to marginalize the exchanges or the circulations transcending national borders and can be quite artificial in regard to certain geographical contexts. The global dimension of beekeeping, especially of Apis mellifera is better considered by Jean-Paul Burdy and the blog “la République des abeilles [the bee Republic]”, where this project of global circulation is at its heart.

It is interesting to note as well that much of the regions covered by the history of beekeeping is Euro-America or China. The other bias is seen to concentrate majorly on one species, Apis mellifera and the story of its dissemination throughout much of the world by different routes, mostly following the path of European colonization at the end of the Middle Ages (15th century). The issue with such a perspective has been to overshadow the history of other traditions worldwide or the interaction of human societies with the rest of the Apis genre. Moreover, the relation between bee species has been, it seems, overlooked even though the arrival of the Apis mellifera and its varieties encountered many local counterparts when the Europeans arrived to control large swaths of the Americas, Asia, Africa and Oceania. It is important in this instance to underline the tension put by the arrival of not only a competitor species but socio-technical system surrounding the bees, putting the traditional beekeeping styles in competition and under pressure.

[1] Dominique Pestre et Stéphane van Damme (eds.), Histoire des sciences et des savoirs, t.2, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 2015, 300 p., Introduction.

[2] Pierre-Henri Tavoillot et François Tavoillot, L’abeille (et le) philosophe: Etonnant voyage dans la ruche des sages, s.l., 2015.

[3] Eric John Hobsbawm, Françoise Braudel et Jean-Claude Pineau, L’ère des révolutions, Paris, Pluriel, 2011.

[4] Eva Crane, The world history of beekeeping and honey hunting, New York, Routledge, 1999, 682 p.

[5] Guillaume Carnino, Liliane Hilaire-Pérez et Aleksandra Kobiljski (eds.), Histoire des techniques : mondes, sociétés, cultures XVIe-XVIIIe siècle, 1re édition., Paris, PUF, 2016, 603 p, pp. 13-4.

[6] Ibid, p. 30.

[7] Gene Kritsky, The quest for the perfect hive: a history of innovation in bee culture, New York, Oxford University Press, 2010, 198 p, pp. 64-5.

[8] E. Crane, The world history of beekeeping and honey hunting, op. cit, pp. 380-1.

[Picture] Bee Museum Rhodes Beekeeping Dodecanese, Notafly, 2010, Link to original image, consulted 5/12/2021.

Looking at the 18th century and 19th: the case of François Huber

We will focus mainly on this part of this article on a particular period which had a profound impact on beekeeping as practice in Euro-America before encountering the rest of the world via different channels. The determining factors were the rise of naturalism or natural sciences during the Early Modern era and the 19th century[1]. During these three centuries, we can notice a significant change of the way we consider bees and how the material surroundings of the bees. These two tendencies could be channeled to a broader trend going on during the Early Modern era. During the 17th century, the analytical framework qualified as the “scientific method” crystallized as a means to understand and to explain the universe in its underlying mechanisms. The rise of science as a tool and a way of thought was probably fueled by the spread of printing technologies at the end of 15th century and by the flourishing of various religious or intellectual movements challenging the supremacy of the Roman Catholic Church in the world of ideas. The connecting thread between Protestantism, Humanism and Enlightenment (with all due conditions taken) is the use of reason and the resulting quest to reason the world and human knowledge, said otherwise[2]. The second important trend was the apparition of (proto-)capitalism and proto-industrialization. The progressive building up of a merchant class in European societies led to a rise in commodity needs in addition to a push for reducing the time taken to manufacture these[3]. The need of capitalism for riches to circulate quickly and in big quantities led to a progressive application of “rationalization” to the means of production and manufacturing.

During this period of time, those long-term phenomena nourished more than two centuries of trial and error in the beekeeping knowledge and technology in order to better understand the functioning of bees and find a way to maximize the productivity of the insects by the same token[4]. Far from linear, the trajectory of knowledge and technology is the mirror of the change of values or needs in any societies over time. This impression of linearity is mainly the product of a retrospective vision towards history, a look to the past where a selection was highlights the most decisive steps of that wandering[5]. In order to exit from the point of view where some lone genius made important breakthroughs in a leapfrogging fashion, the research has concentrated on the unfolding of these technological changes put in their social context. By implementing the socio-environmental context of the rise of production-driven agriculture, one grasps the mutual causal loop linking both elements on different timescales[6].

The contributors of this profound change in beekeeping were mostly men who benefited from a network of people and resources, without mentioning the work of their predecessors. By trial after trial, personalities like Jan Swammerdam, Lorenzo Langstroth or François Huber are a nebulous of protagonists who had the luck to enjoy a good combination to make a contribution that is still remembered nowadays[7]. The first major step was the discovery of the biology of bees and the understanding of their social structure. The elaboration of the microscope by Jan Swammerdam allowed the first naturalists or people of knowledge without having a better word to designate them to see in detail the intimacy of a beehive[8]. There was discovered the fact that the head of the hive was a queen instead of a king and the reproductive cycle of the bees. The second primordial discovery was the communication of bees. Being the foundational stone of social insects, the use of pheromones and bodily language allows the individuals to communicate and organize their lives inside the colony.

During this period of time, those long-term phenomena nourished more than two centuries of trial and error in the beekeeping knowledge and technology in order to better understand the functioning of bees and find a way to maximize the productivity of the insects by the same token[4]. Far from linear, the trajectory of knowledge and technology is the mirror of the change of values or needs in any societies over time. This impression of linearity is mainly the product of a retrospective vision towards history, a look to the past where a selection was highlights the most decisive steps of that wandering[5]. In order to exit from the point of view where some lone genius made important breakthroughs in a leapfrogging fashion, the research has concentrated on the unfolding of these technological changes put in their social context. By implementing the socio-environmental context of the rise of production-driven agriculture, one grasps the mutual causal loop linking both elements on different timescales[6].

The contributors of this profound change in beekeeping were mostly men who benefited from a network of people and resources, without mentioning the work of their predecessors. By trial after trial, personalities like Jan Swammerdam, Lorenzo Langstroth or François Huber are a nebulous of protagonists who had the luck to enjoy a good combination to make a contribution that is still remembered nowadays[7]. The first major step was the discovery of the biology of bees and the understanding of their social structure. The elaboration of the microscope by Jan Swammerdam allowed the first naturalists or people of knowledge without having a better word to designate them to see in detail the intimacy of a beehive[8]. There was discovered the fact that the head of the hive was a queen instead of a king and the reproductive cycle of the bees. The second primordial discovery was the communication of bees. Being the foundational stone of social insects, the use of pheromones and bodily language allows the individuals to communicate and organize their lives inside the colony.

[9] G. Kritsky, The quest for the perfect hive, op. cit, chapters 8-12.

[10] Ibid, pp. 81-2.

[11] Ibid, p. 128.

[12] E. Crane, The world history of beekeeping and honey hunting, op. cit, p. 345.

[Picture] Portrait of François Huber (1750-1821), Unknown painter, Link to original image, consulted 5/12/2021.

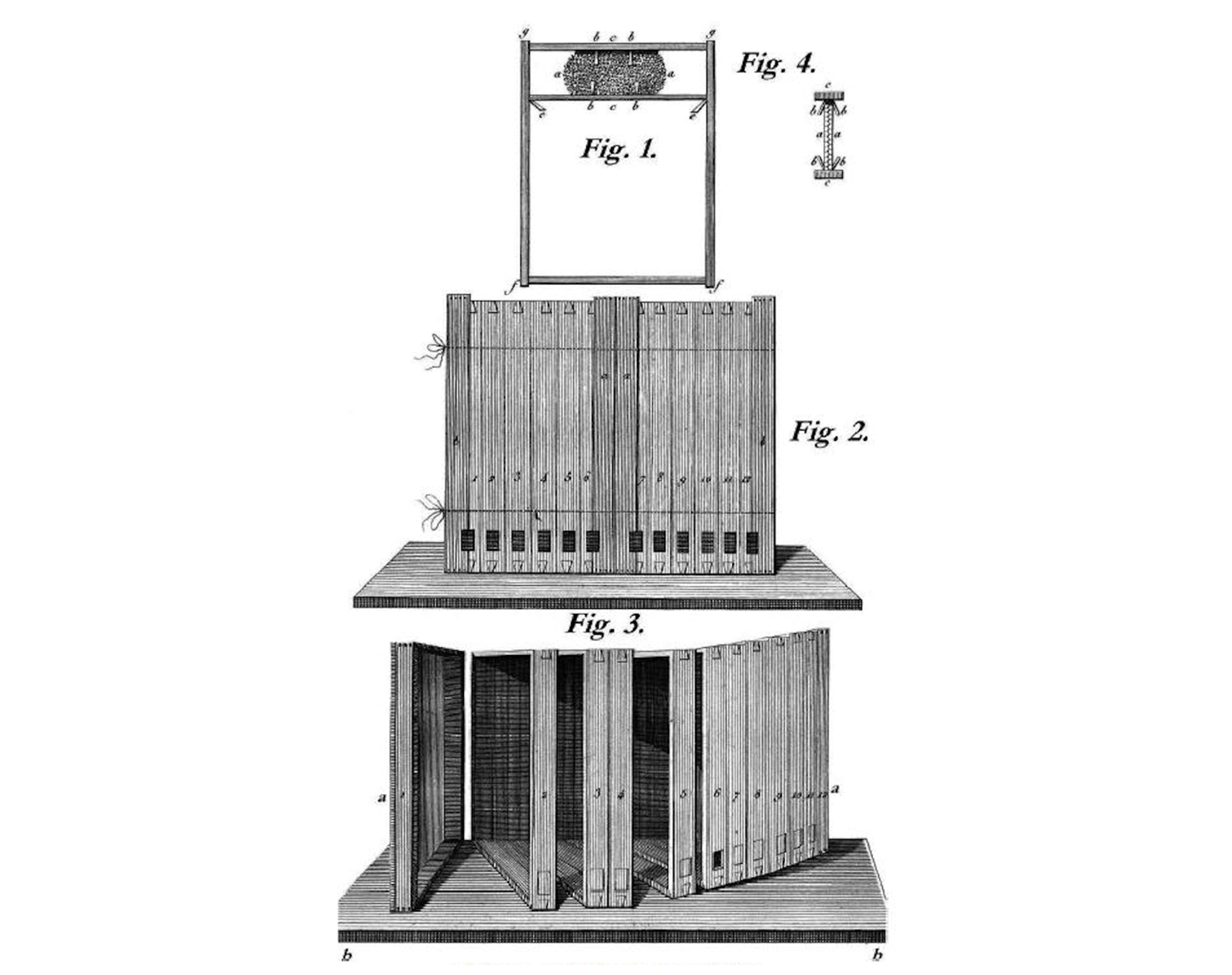

In parallel, the evolution of apiaries and the equipment used in beekeeping, which hasn’t really never stopped, changed faster in accordance with the amelioration of knowledge about the behavior of bees and their biology. The 17th-19th centuries were in this regard rich of technical advancements and the apparition of the contemporary beehive, as Gene Kristky underlines it[9]. The apiaries of this period of time was fertile in trials of numerous alternative models of beehives, in contrast to the straw baskets originally used for beekeeping. Instead of being built out of a single piece where bees nested, the new models are distinctive by their dismountable design and the mobile framing where bees can fix their colony. As G. Kristky points out, the apparition of this new type of wooden apiaries resulted from new local conditions. In North America, the abundance of cheap wood led to an adoption of less mobile, but more durable shelters for bees. Moreover, the period was quite adventurous in the design of beehives because each settler community respond to their local needs[10]. In addition to a technical speciation process, one notices that there was a push for an optimal hive for the biological needs of bees during the 19th century on both sides of the Atlantic. The turn of the 20th century marked the supremacy of the wooden beehive on straw apiaries, still largely used then, mostly for its light weight when beekeepers had to displace then from one field to another by bicycle. The situation changed with the adoption at a large scale of motorized transport, where weight mattered less[11].

The aim of such a change in the fashion of the hives was to spare the life of colonies and to increase the amount of honey produced. Before the invention of mobile frames hives, the fate of most colonies was to be killed by asphyxia before extracting honey from the hive. Mobile frames avoided the destruction of bees by smoking and to yield honey without disturbing the bees too much by creating an opening by the roof of the hive or by a hind door depending on the local preference and the aggressivity of their inhabitants. It was considered that it was wasteful to eliminate colonies, even more so once the solution of splitting colonies let them alive and taking the queen away. Less stress for the animals and a better protection from the outside world allowed the bees to have a more stable environment and to be more productive[12].

The aim of such a change in the fashion of the hives was to spare the life of colonies and to increase the amount of honey produced. Before the invention of mobile frames hives, the fate of most colonies was to be killed by asphyxia before extracting honey from the hive. Mobile frames avoided the destruction of bees by smoking and to yield honey without disturbing the bees too much by creating an opening by the roof of the hive or by a hind door depending on the local preference and the aggressivity of their inhabitants. It was considered that it was wasteful to eliminate colonies, even more so once the solution of splitting colonies let them alive and taking the queen away. Less stress for the animals and a better protection from the outside world allowed the bees to have a more stable environment and to be more productive[12].

[13] Piguet, Martine; Terrier, Jean; DHS DSS, HLS; Mottu-Weber, Liliane; Herrmann, Irène; Heimberg, Charles: "Genève (canton)", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version du 30.05.2017.

Online ref, consulted on 16.12.2021.

[14] Sigrist, René: "Huber, François", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version du 29.04.2008. Online ref, consulted on 19.12.2021.

[15] Piguet, Martine; Terrier, Jean; Bonnet, Charles; rédaction, La; Mottu-Weber, Liliane; Herrmann, Irène; Heimberg, Charles: "Genève (commune)", in: Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse (DHS), version du 07.02.2018. Online ref, consulted on 19.12.2021.

[16] Anton Vos, « François Huber, roi des abeilles », in :Campus, consulted on 19.12.2021.

[17] François Huber, Journal de ma ruche et autres observations, expériences relatives aux abeilles durant l’année 1776, 1776, BGE Msfr 1259, Library of Geneva.

In this panorama, François Huber (1750-1821) was no exception to the linage of beekeepers and naturalists trying to understand these insects better. The Swiss naturalist is well integrated into the framework of the Genevan educated society of the Enlightenment during the 18th and 19th centuries[13]. He is mostly known for being the inventor of the mobile frame hive and for its classical book New observations on the natural history of bees published for the first time in 1814, re-edited multiple times after its initial publication. His familial background is anchored in a military and educated environment, being relatively protected from poverty[14]. This circumstance is cemented by the marriage of François Huber with Marie-Aimée Lullin, who was the daughter of Pierre Lullin, a renowned lawyer and the syndic of Geneva twice in 1728 and 1732, one of the top posts of the Genevan government.

The presence of an important entomologist in Geneva during the 18th century is no shocker, even a helping factor to the rise of reputed scientific profiles. The city-state was during the Early Modern era a shelter, a refuge for Protestants fleeing the neighboring catholic territories and took with them multiple assets and a network of relations spreading all across Europe. Known also as the “Protestant Rome” since the 16th century, Geneva emitted an aura of welcoming home for exiled personalities and intellectual hub. The city and its surroundings were the birthplace of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and housed one of the most renowned philosophers of Enlightenment, Voltaire (by his true name Jean-Marie Arouet)[15]. By the time of François Huber’s birth, the City of Calvin hosted a vibrant intellectual life and several scientific dynasties such as the Saussure or the De Candolle for example.

Postal exchanges between Huber and his relatives meant that he was integrated in a network where ideas, concepts and theories circulated. More importantly, the work of François Huber was the result of a collective work of such a network and the collaboration of his household. François Burnens, who worked first as his henchman, became progressively his most precious collaborator, his eyes per say. Indeed, the man was blind since his twenties and could only make assumptions and verify through the lens of his assistant[16]. In a sense, Burnens was co-opted by higher levels of society in favor of his proximity to Huber and the key-role he had in the knowledge producing process of François Huber. François Burnens took this vital role even more after the death of Marie-Aimée Lullin in 1822, becoming an emotional support for the one who deemed him as a dear friend and his eyes. Moreover, as Huber lost sight pretty early in his life, it wouldn’t be surprising to hypothesize that the journal he wrote for several years was in fact written by her wife or his henchman. In a more literary standpoint, one may wonder who was behind the subject “I” since the journal was written at the first person. It is more probable that research in the context of the Huber family was a household business even though the first-person formulation omits this mixed reality for stressing the master mind behind the observations[17].

The presence of an important entomologist in Geneva during the 18th century is no shocker, even a helping factor to the rise of reputed scientific profiles. The city-state was during the Early Modern era a shelter, a refuge for Protestants fleeing the neighboring catholic territories and took with them multiple assets and a network of relations spreading all across Europe. Known also as the “Protestant Rome” since the 16th century, Geneva emitted an aura of welcoming home for exiled personalities and intellectual hub. The city and its surroundings were the birthplace of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and housed one of the most renowned philosophers of Enlightenment, Voltaire (by his true name Jean-Marie Arouet)[15]. By the time of François Huber’s birth, the City of Calvin hosted a vibrant intellectual life and several scientific dynasties such as the Saussure or the De Candolle for example.

Postal exchanges between Huber and his relatives meant that he was integrated in a network where ideas, concepts and theories circulated. More importantly, the work of François Huber was the result of a collective work of such a network and the collaboration of his household. François Burnens, who worked first as his henchman, became progressively his most precious collaborator, his eyes per say. Indeed, the man was blind since his twenties and could only make assumptions and verify through the lens of his assistant[16]. In a sense, Burnens was co-opted by higher levels of society in favor of his proximity to Huber and the key-role he had in the knowledge producing process of François Huber. François Burnens took this vital role even more after the death of Marie-Aimée Lullin in 1822, becoming an emotional support for the one who deemed him as a dear friend and his eyes. Moreover, as Huber lost sight pretty early in his life, it wouldn’t be surprising to hypothesize that the journal he wrote for several years was in fact written by her wife or his henchman. In a more literary standpoint, one may wonder who was behind the subject “I” since the journal was written at the first person. It is more probable that research in the context of the Huber family was a household business even though the first-person formulation omits this mixed reality for stressing the master mind behind the observations[17].

[18] D. Pestre et S. van Damme (eds.), Histoire des sciences et des savoirs, op. cit., p. 26.

[19] P.-H. Tavoillot et F. Tavoillot, L’abeille (et le) philosophe, op. cit, pp. 245-6.

[20] Jean-Paul Burdy, « Le Roi des abeilles »: « Confusion des sexes dans la ruche et genre du pouvoir politique en Europe à l’Epoque moderne (XVIe-XVIIIe s.) », Online ref, consulted on 19.12.2021.

[21] E. Crane, The world history of beekeeping and honey hunting, op. cit, pp. 380-1.

[22] François Huber, « Nouvelles Observations sur les abeilles », J.-J. Paschoud, Paris, 1814, pp. 78-9.

[23] E. Crane, The world history of beekeeping and honey hunting, op. cit, chapter 40.

[24] P.-H. Tavoillot et F. Tavoillot, L’abeille (et le) philosophe, op. cit.

[25] François Huber, Journal de ma ruche et autres observations, expériences relatives aux abeilles durant l’année 1776, 1776, BGE Msfr 1259, Library of Geneva, pp. 46-7.

[26] François Huber, Journal de ma ruche et autres observations, expériences relatives aux abeilles durant l’année 1776, 1776, BGE Msfr 1259, Library of Geneva, pp. 4-5

[27] François Huber, Journal de ma ruche et autres observations, expériences relatives aux abeilles durant l’année 1776, 1776, BGE Msfr 1259, Library of Geneva, p. 11.

[28] François Huber, Journal de ma ruche et autres observations, expériences relatives aux abeilles durant l’année 1776, 1776, BGE Msfr 1259, Library of Geneva, p.6.

[Picture] François Huber’s model of apiary with horizontal frames for a better extraction of honey, 1814, in: Nouvelles Observations sur les abeilles, adressées à Charles Bonnet, Link to original image, consulted on 9/12/2021.

New observations: the bees as a scientific object

As mentioned in the article, the way we considered bees changed at an accelerated rate during the Early Modern era. We analyze in this part how this insight morphed through time, especially by dissecting the work of the aforementioned Swiss naturalist François Huber. The evolution of honeybees as scientific objects followed the more global trend operating during the 16th to the 19th century with the rise of naturalism and the discipline called “Natural History”[18]. During this span of a few centuries, the bee has seen a diminution of its theological charge, since the references made to honeybees and their social structure made a strong image used for diverse aims by the many philosophers and thinkers during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment[19]. The social organization inside the colonies, with a strict hierarchy and a monarch at its top was used as a parable for the model societies or political thinkers, where order and tidiness would prevail. In other words, bees could be used as a screen to project the ideals of a given society at some point[20].

This dimension was challenged by the breakthroughs made by the accumulation of works by different proto-scientists and naturalists throughout the period. The black box of colony’s internal organization has been demystified with the unveiling of intricate relationships between individuals, forming some kind of superorganism. By use of the microscope to the world of beekeeping[21]. Naturalists didn’t only understand better the intimacy of a hive but the internal functioning of bees as living organisms. By layering different levels of observation on the microscopic and macroscopic scales, the naturalists would decipher the purpose of organs and the role they play in the life cycle of a bee depending on its position in the colony’s social ladder. The stages inside a cycle would differ from a queen to a worker. The queen received a lot of attention from the contributions of those who investigated the matter. Being at the highest position in the nest, grasping the conditions leading to her rise and her behavior was the key to comprehend the global functioning of one hive. In his New Observations, François Huber tried to investigate the role of the queen bee: “In another trial we gave to the bees a hive without a queen, brood and pollen; we saw immediately the small tiny honeybees taking care of the larvae’s food, whereas the waxing class didn’t take care at all.

When the hive is full of cake, the waxing bees disgorge their honey into the ordinary warehouses and don’t make wax; but even if they do not have storage to stock it, and if the queen doesn’t find any ready cells for laying her eggs, they keep the honey they collected in the stomac, and after twenty-four hours the wax oozes between their rings; then begins the comb’s work.”[22]

At the center of those observations, the honeybee developed a new status, interacting with the other roles attributed to the insect through the ages. Due to the development of the regime in the validation of a theory by a proof backed by experimentation, the well-studied insect became a subject of experimentation. It implied that honeybees were put into certain conditions thought as reproducible in order to validate by repetition some assumptions from previous observations on the terrain. The status of Apis mellifera was not only the result of chance, the product of arguments leading to its selection as an experimental device. The explanation could be found in the creation of the sub-field of biology called entomology, the study of insects[23]. The objectives of this field of naturalism were the categorization of the abundance of insect species on earth, the uncovering of their life cycle and the description of the mechanisms behind metamorphosis, considered as the most fascinating phenomenon of the insect world. Honeybees are the perfect subject of study for the newly created discipline because they were at the time well known creatures and one of the few domesticated insect species by man. The hives could be placed in a given place that could be displaced in diverse contexts of observation and with a massive population of specimens for study[24].

The combination of the proximity and the actual lack of knowledge about detailed bees’ mechanisms entomologists had led them to select these social beings as subject of experimentation. On the field, the observations made by François Huber and his collaborators were made by considering the bees as an inductive system of enigmas that could be answered by following a protocol implying a succession of tests. The results obtained from the tests would confirm or infirm the theory formulated by Huber or his colleagues in different corners of Europe. The main subjects of contention at heart are the observations about beeswax and the way honey was produced, based on pollen[25]. We can see at this point that Huber and his collaborators weren’t still unsure of the processes behind the production, until we discovered the separate origins of both substances. By making references to his colleagues and arguing on their ideas, Huber inserts himself in a network of scientists interested in honeybees and by the same token pursuing a collaborative tradition developing in the 18th century onwards.

In order to observe at best his object of study, Huber installed around 1776 an apiary with a mirror in his garden and two thermometers inside and outside of the hive. Along with these installations, experimentation shapes the daily life of the naturalist[26]. Huber wrote in his journal, covering the years from 1776 to 1782, the observations he made from his colony in relation with the outside weather and the ambient temperature[27]. With a quasi-daily regularity, the bees were observed early in the morning, at noon or at dusk. Beside the link he tried to make between bee behavior and their environment, François Huber consigned precisely the functioning of the hive during the productive season. He observed in 1776: “I didn’t see perhaps the combined cake. On the 1st, I happened to open the shutters at hours where the bees went out to collect pollen. They empty the apiary because today I had a lot of trouble to see them”

This dimension was challenged by the breakthroughs made by the accumulation of works by different proto-scientists and naturalists throughout the period. The black box of colony’s internal organization has been demystified with the unveiling of intricate relationships between individuals, forming some kind of superorganism. By use of the microscope to the world of beekeeping[21]. Naturalists didn’t only understand better the intimacy of a hive but the internal functioning of bees as living organisms. By layering different levels of observation on the microscopic and macroscopic scales, the naturalists would decipher the purpose of organs and the role they play in the life cycle of a bee depending on its position in the colony’s social ladder. The stages inside a cycle would differ from a queen to a worker. The queen received a lot of attention from the contributions of those who investigated the matter. Being at the highest position in the nest, grasping the conditions leading to her rise and her behavior was the key to comprehend the global functioning of one hive. In his New Observations, François Huber tried to investigate the role of the queen bee: “In another trial we gave to the bees a hive without a queen, brood and pollen; we saw immediately the small tiny honeybees taking care of the larvae’s food, whereas the waxing class didn’t take care at all.

When the hive is full of cake, the waxing bees disgorge their honey into the ordinary warehouses and don’t make wax; but even if they do not have storage to stock it, and if the queen doesn’t find any ready cells for laying her eggs, they keep the honey they collected in the stomac, and after twenty-four hours the wax oozes between their rings; then begins the comb’s work.”[22]

At the center of those observations, the honeybee developed a new status, interacting with the other roles attributed to the insect through the ages. Due to the development of the regime in the validation of a theory by a proof backed by experimentation, the well-studied insect became a subject of experimentation. It implied that honeybees were put into certain conditions thought as reproducible in order to validate by repetition some assumptions from previous observations on the terrain. The status of Apis mellifera was not only the result of chance, the product of arguments leading to its selection as an experimental device. The explanation could be found in the creation of the sub-field of biology called entomology, the study of insects[23]. The objectives of this field of naturalism were the categorization of the abundance of insect species on earth, the uncovering of their life cycle and the description of the mechanisms behind metamorphosis, considered as the most fascinating phenomenon of the insect world. Honeybees are the perfect subject of study for the newly created discipline because they were at the time well known creatures and one of the few domesticated insect species by man. The hives could be placed in a given place that could be displaced in diverse contexts of observation and with a massive population of specimens for study[24].

The combination of the proximity and the actual lack of knowledge about detailed bees’ mechanisms entomologists had led them to select these social beings as subject of experimentation. On the field, the observations made by François Huber and his collaborators were made by considering the bees as an inductive system of enigmas that could be answered by following a protocol implying a succession of tests. The results obtained from the tests would confirm or infirm the theory formulated by Huber or his colleagues in different corners of Europe. The main subjects of contention at heart are the observations about beeswax and the way honey was produced, based on pollen[25]. We can see at this point that Huber and his collaborators weren’t still unsure of the processes behind the production, until we discovered the separate origins of both substances. By making references to his colleagues and arguing on their ideas, Huber inserts himself in a network of scientists interested in honeybees and by the same token pursuing a collaborative tradition developing in the 18th century onwards.

In order to observe at best his object of study, Huber installed around 1776 an apiary with a mirror in his garden and two thermometers inside and outside of the hive. Along with these installations, experimentation shapes the daily life of the naturalist[26]. Huber wrote in his journal, covering the years from 1776 to 1782, the observations he made from his colony in relation with the outside weather and the ambient temperature[27]. With a quasi-daily regularity, the bees were observed early in the morning, at noon or at dusk. Beside the link he tried to make between bee behavior and their environment, François Huber consigned precisely the functioning of the hive during the productive season. He observed in 1776: “I didn’t see perhaps the combined cake. On the 1st, I happened to open the shutters at hours where the bees went out to collect pollen. They empty the apiary because today I had a lot of trouble to see them”

This naturalistic, even entomological manner to consider A. mellifera has several consequences on how the animals are perceived and the living of hives, during and beyond the time of François Huber. Honeybees were in consequence exposed to a variety of experiments and observations, with the background hives becoming an experimentation ground. We can consider honeybees as one of the first insects in history to be used as an experimentation animal in the arthropod world. The backyard in this respect is a form of laboratory, along with the office of François Huber, where his tools were located. Even though the ground where the hives were dedicated to the sole purpose of comprehension and analysis, it would be a stretch to consider them as proper laboratories. The principal difference was situated in the control of the environmental conditions of observation. For the sake of validity, the deductions were made on repeated experiments, the conditions presiding each experiment had to be consistent to draw valid conclusions from a trial. On the other hand, the laboratory as we conceive it didn’t exist until the second half of the 19th century, when laboratories welcomed team research, mostly dedicated to natural sciences such as chemistry and physics. We could hence consider experimental hives and their surroundings as some kind of proto-laboratory or the semi-controlled environment. The principal limit was the lifestyle of bees gathering pollen outside didn’t allow bees to put bees in a controlled environment indoors.

The second consequence from the status of bees as experimental animals is the complexification of the relationship between bees and humans by deepening knowledge about those Hymenoptera. A better comprehension of the Apis genre allowed a co-modification of the tools and the practical know-how in order to fit better the theoretical knowledge developed by the first entomologists. It was not only a catch-up of the new standards based on a renewed comprehension. More complexly, the technical landscape surrounding the art of beekeeping was simultaneously a fuel for further research and in return ameliorated it. The biggest achievements were made thanks to the emergence of modern beekeeping in the techniques regarding the extraction of honey, beeswax and propolis. Beehives in racks and the fumigation combined are the keys to take the precious materials away without killing the colony like it used to be in previous centuries.

Beekeepers benefited also from François Huber’s work and his homologous. The strengthening of the comprehension around bees lead to a professionalization of the activity. The end of the 18th century and the turn of the 19th marked a transition from a handcraft activity to a more formalized form of specialized labor. The reason behind this change originated from the requirements needed by the evolution of this very activity. The sum of knowledge accumulated necessitated a longer apprenticeship to learn about the functioning of the honeybees. The specialization brought by the professionalization of the branch led to a need of more precise manutentions brought by the grasping of the specific needs of beehives. Alimented by the modification of the nature of labor itself, specialization meant as well an extended dedication to the care of hives until being a full-time activity during high season. The fact to keep the bees alive through winter had as another consequence to lower the production costs of honey and gave the financial width to beekeepers to increase the number of beehives, hence the overall quantity of honey produced by beekeepers.

The experimental status of honeybees led to a renewal of the symbolic and productive statuses of the insects. The search for productivity and rentability from hives led to considering bees in a more materialist, mechanical fashion. Such a view was reinforced by the naturalistic stance of the Enlightenment in natural sciences. As Voltaire compared the world and the universe as some kind of clockwork, the natural world has come to be considered as a big structure whose rules had to be deciphered. Much like watches, the bees were seen like organisms functioning on more or less principles. Once mastered, one could manipulate and try to modify the object based on these same rules.

In this instance, animal husbandry and the advancements made in the taxonomy of species of bees laid the ground for experimentation to deliberately select traits and to express them through crossing different varieties. In other words, modern beekeeping modified both the technoscape of that craft and even the animals themselves with the means of the time. This approach was more radical than the simple change of know-how, but it implied the manipulation of bees themselves to suit the expectations and the needs of beekeepers. Even though domestication and artificial selection didn’t occur at the end of the Early Modern era, it seems that the discoveries of Linnaeus or Lamarck augmented the consciousness behind the potential of selection and crossbreeding.

The symbolic function of the bees was altered as well. The insects in question weren’t considered as very intelligent beings either, in spite of the organizational intelligence that conferred them some recognition from their observers. The materialist point of view and additional lack of recognition for the collective intelligence of bees, participated in a larger phenomenon. As mentioned before, Apis mellifera was mostly considered for its well-organized structure and their cohesion, without omitting their industriousness. For this very reason, the “honey flies” were the emblem of French royalty, stressing the values that were attached to these animals. A shift in the overall comprehension of the bees led to enrichment of the way that Early Modern mentalities placed bees in relationships on the web of the living. With the rise of the “naturalistic” bee, the theological charge attached to honeybees faded slowly to be replaced by a philosophical representation. In this regard, the key-place it occupied in the Christian vision of Nature was conserved by the understanding of the pollinating role occupied by honeybees. The beginnings of ecology allowed naturalists to grasp the link between flower plants and pollinators and how this relationship could be used for human activities.

Beekeepers benefited also from François Huber’s work and his homologous. The strengthening of the comprehension around bees lead to a professionalization of the activity. The end of the 18th century and the turn of the 19th marked a transition from a handcraft activity to a more formalized form of specialized labor. The reason behind this change originated from the requirements needed by the evolution of this very activity. The sum of knowledge accumulated necessitated a longer apprenticeship to learn about the functioning of the honeybees. The specialization brought by the professionalization of the branch led to a need of more precise manutentions brought by the grasping of the specific needs of beehives. Alimented by the modification of the nature of labor itself, specialization meant as well an extended dedication to the care of hives until being a full-time activity during high season. The fact to keep the bees alive through winter had as another consequence to lower the production costs of honey and gave the financial width to beekeepers to increase the number of beehives, hence the overall quantity of honey produced by beekeepers.

The experimental status of honeybees led to a renewal of the symbolic and productive statuses of the insects. The search for productivity and rentability from hives led to considering bees in a more materialist, mechanical fashion. Such a view was reinforced by the naturalistic stance of the Enlightenment in natural sciences. As Voltaire compared the world and the universe as some kind of clockwork, the natural world has come to be considered as a big structure whose rules had to be deciphered. Much like watches, the bees were seen like organisms functioning on more or less principles. Once mastered, one could manipulate and try to modify the object based on these same rules.

In this instance, animal husbandry and the advancements made in the taxonomy of species of bees laid the ground for experimentation to deliberately select traits and to express them through crossing different varieties. In other words, modern beekeeping modified both the technoscape of that craft and even the animals themselves with the means of the time. This approach was more radical than the simple change of know-how, but it implied the manipulation of bees themselves to suit the expectations and the needs of beekeepers. Even though domestication and artificial selection didn’t occur at the end of the Early Modern era, it seems that the discoveries of Linnaeus or Lamarck augmented the consciousness behind the potential of selection and crossbreeding.

The symbolic function of the bees was altered as well. The insects in question weren’t considered as very intelligent beings either, in spite of the organizational intelligence that conferred them some recognition from their observers. The materialist point of view and additional lack of recognition for the collective intelligence of bees, participated in a larger phenomenon. As mentioned before, Apis mellifera was mostly considered for its well-organized structure and their cohesion, without omitting their industriousness. For this very reason, the “honey flies” were the emblem of French royalty, stressing the values that were attached to these animals. A shift in the overall comprehension of the bees led to enrichment of the way that Early Modern mentalities placed bees in relationships on the web of the living. With the rise of the “naturalistic” bee, the theological charge attached to honeybees faded slowly to be replaced by a philosophical representation. In this regard, the key-place it occupied in the Christian vision of Nature was conserved by the understanding of the pollinating role occupied by honeybees. The beginnings of ecology allowed naturalists to grasp the link between flower plants and pollinators and how this relationship could be used for human activities.

Conclusion: limitations to the observations

Throughout this article, the chronology of beekeeping for the species Apis mellifera was explored. The article demonstrated that the period between 17th to the mid 19th century is a pivotal period for the history of beekeeping. The emergence of science as we know it influenced the way we conceptualized bees and how we interacted with these beings. One of the main actors of this shift was the Swiss entomologist François Huber, who worked in a network that allowed him and his collaborators to understand honeybees in a seminal way for the 19th century. The actualized knowledge was evolving in parallel with the technology dedicated to care for the colonies and to extract different products of bees.

There are, however, final precautions to take with the present conclusions. The evolutions drawn from the analysis of the work of François Huber is mostly confined at first into a certain social group to which belonged Huber, before spreading significantly during the 19th century. Based on the conclusions of Gene Kristky, the generalization of the apiaries format familiar to us today dates back only to the turn of the 19th and 20th century, mostly in the Anglo-American world. The explanation lies in the technological factor: the invention by Lorenzo Langstroth of beehives containing the bee space and the discovery of centrifugation for honey extraction. Both factors made the adoption of framed apiaries financially interesting for beekeepers, who progressively abandoned the skep made of straw, easier to transport due to light weight and their low price.

There are, however, final precautions to take with the present conclusions. The evolutions drawn from the analysis of the work of François Huber is mostly confined at first into a certain social group to which belonged Huber, before spreading significantly during the 19th century. Based on the conclusions of Gene Kristky, the generalization of the apiaries format familiar to us today dates back only to the turn of the 19th and 20th century, mostly in the Anglo-American world. The explanation lies in the technological factor: the invention by Lorenzo Langstroth of beehives containing the bee space and the discovery of centrifugation for honey extraction. Both factors made the adoption of framed apiaries financially interesting for beekeepers, who progressively abandoned the skep made of straw, easier to transport due to light weight and their low price.