The arrival of Apis mellifera to Japan, part 2

Published:: 2024-01-08

Author:: William Favre

Topics:: [Environment] [Science] [Animals]

Related articles::

[Apis mellifera in history, part 1]

[Apis mellifera in history, part 1]

[1] Eva Crane, The world history of beekeeping and honey hunting, New York, Routledge, 1999, 682 p., chap. 31.

[2] Ibid., p. 546.

[3] Ibid., pp.310-1.

[4] Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing et al., Feral atlas: the more-than-human Anthropocene, s.l., 2020, "Acceleration".

[5] Martin Husemann et al., « The northernmost record of the Asian hornet Vespa velutina nigrithorax (Hymenoptera, Vespidae) », Evolutionary Systematics, 4 février 2020, vol. 4, no 1, p. 1‑4.

[6] Mark Ravina et Oxford University Press, To stand with the nations of the world: Japan’s Meiji restoration in world history, New York, NY, Oxford University Press, 2017, pp.155-168.

[7] Masayuki Tanimoto (ed.), The role of tradition in Japan’s industrialization: another path to industrialization, Oxfort ; New York, Oxford University Press, 2006, 342 p, p. 4.

[8] Rachel Datinger, “Reconsidering Non-native Species”, in: Naked Scientist, 17.12.2012,

View source, consulted on 06.02.2022.

Introduction: a case study

In this second part of the environmental history of beekeeping, we will concentrate on the determinant dimension of the history of Apis mellifera: globalization. As mentioned in the first part, A. mellifera followed the expansion of Europeans’ political and economic impact starting from the 16th century onwards. It spread first to the Americas before penetrating dramatically in the interior of the other continents during the 18th and the 19th century[1]. The arrival of the Europeans settlers or knowledge was welcomed in three ways, either endured, deliberate or a mix between these two options. The preexisting local beekeeping culture took its toll and saw their respective trajectories diverge in different ways depending on domestic contingencies.

On the ecological level, the apparition of a new species in an ecosystem meant major perturbations among the local wild bees and pollinator species. The environmental consequence of the introduction of the settlers’ honeybee into a new habitat was the competition that began between domestic and wild species[2]. The reduction of their natural habitat plus the competition for food led to a decrease in the number of the local microfauna, the species in direct competition literally dying of hunger. In the case study of Japan, oppositely to Australia or North America, had not the best suited environment for the Euro-American varieties of honeybee[3]. The main hurdle to Apis mellifera’s expansion in Japan and more broadly in East Asia was represented by hornets. As we will detail further in this paper, the Asian hornet or Vespa velutina was one of the reasons explaining the relative absence of A. mellifera on the archipelago. Beyond environmental causes, culture has played a significant role in the trajectory of the Western bee on the archipelago.

The flipside of the coin has the tendency to be an unexpected consequence of a process taking place for a certain purpose. In our case, the profound reconnection of the circulation routes on a global scale, added to the intensification in volume and rate would backfire on the initiating territories on multiple levels. When the Asian hornet set foot in Europe at the turn of the century, it wasn’t the first nor the last species to disembark from the transportation that took them from the home environment[4]. Actually, the Asian hornet took the opposite route taken by Apis mellifera when it arrived in Japan or the Asian mainland. In Europe, without any natural predator, the Asian hornet could freely expand its repartition area and feast on an Apis species that has not any of the tools developed by Asia cerana to counter their predator[5].

The article demonstrates how beekeeping could be used for a study on a global scale for environmental exchange of species and how cultural factors have to be taken into consideration. The other stake in this article is to prove that the dramatic expansion of the presence of A. mellifera in the world can’t be considered a one-way phenomenon as imposed and coming from Euro-America only. In certain cases, the presence of the Western bee was deliberate and the fruit of local conditions, not to mention the circulation of living organisms and goods provoked by capitalism. The third point of demonstration argues that globalization isn’t an entirely controlled force by its initiators and might not be bound to one orientation.

In this instance, the Japanese archipelago would play the role of case study in this article. Japan, starting from the later years of the Edo period, began to intensify its exchanges with the powers with whom the Shogunate signed asymmetrical commercial treaties. Conscious of the semi-colonial in which the Qing empire has been enduring as a result of the Opium wars, the strategy adopted by the Tokugawa Shogunate and resumed by the Imperial regime consisted in the adoption of the tools coming from the Western Powers, in different domains[6]. In the agronomical world, the same trend could be found. A partnership between public and private actors drove the adoption and the subsequent adaptation of the selected tools to the local context[7]. Beekeeping is among one of the domains affected by this evolution towards a new type of agronomy.

The second part would look in the opposite direction to Europe, in order to link the career of V. velutina with the A. mellifera and A. cerana’s own histories. The intensification of global trade during the two last centuries rippled on local biosystems by major perturbations under the appearance of species that were put out of their native environmental context. The term “invasive species” would have to be taken with precautions because it is the fruit of our own human cognition of the interaction between species instead of an onslaught of a given species upon an entire region[8].

On the ecological level, the apparition of a new species in an ecosystem meant major perturbations among the local wild bees and pollinator species. The environmental consequence of the introduction of the settlers’ honeybee into a new habitat was the competition that began between domestic and wild species[2]. The reduction of their natural habitat plus the competition for food led to a decrease in the number of the local microfauna, the species in direct competition literally dying of hunger. In the case study of Japan, oppositely to Australia or North America, had not the best suited environment for the Euro-American varieties of honeybee[3]. The main hurdle to Apis mellifera’s expansion in Japan and more broadly in East Asia was represented by hornets. As we will detail further in this paper, the Asian hornet or Vespa velutina was one of the reasons explaining the relative absence of A. mellifera on the archipelago. Beyond environmental causes, culture has played a significant role in the trajectory of the Western bee on the archipelago.

The flipside of the coin has the tendency to be an unexpected consequence of a process taking place for a certain purpose. In our case, the profound reconnection of the circulation routes on a global scale, added to the intensification in volume and rate would backfire on the initiating territories on multiple levels. When the Asian hornet set foot in Europe at the turn of the century, it wasn’t the first nor the last species to disembark from the transportation that took them from the home environment[4]. Actually, the Asian hornet took the opposite route taken by Apis mellifera when it arrived in Japan or the Asian mainland. In Europe, without any natural predator, the Asian hornet could freely expand its repartition area and feast on an Apis species that has not any of the tools developed by Asia cerana to counter their predator[5].

The article demonstrates how beekeeping could be used for a study on a global scale for environmental exchange of species and how cultural factors have to be taken into consideration. The other stake in this article is to prove that the dramatic expansion of the presence of A. mellifera in the world can’t be considered a one-way phenomenon as imposed and coming from Euro-America only. In certain cases, the presence of the Western bee was deliberate and the fruit of local conditions, not to mention the circulation of living organisms and goods provoked by capitalism. The third point of demonstration argues that globalization isn’t an entirely controlled force by its initiators and might not be bound to one orientation.

In this instance, the Japanese archipelago would play the role of case study in this article. Japan, starting from the later years of the Edo period, began to intensify its exchanges with the powers with whom the Shogunate signed asymmetrical commercial treaties. Conscious of the semi-colonial in which the Qing empire has been enduring as a result of the Opium wars, the strategy adopted by the Tokugawa Shogunate and resumed by the Imperial regime consisted in the adoption of the tools coming from the Western Powers, in different domains[6]. In the agronomical world, the same trend could be found. A partnership between public and private actors drove the adoption and the subsequent adaptation of the selected tools to the local context[7]. Beekeeping is among one of the domains affected by this evolution towards a new type of agronomy.

The second part would look in the opposite direction to Europe, in order to link the career of V. velutina with the A. mellifera and A. cerana’s own histories. The intensification of global trade during the two last centuries rippled on local biosystems by major perturbations under the appearance of species that were put out of their native environmental context. The term “invasive species” would have to be taken with precautions because it is the fruit of our own human cognition of the interaction between species instead of an onslaught of a given species upon an entire region[8].

[9] Howard R. Hepburn (ed.), Honeybees of Asia, Berlin Heidelberg, Springer, 2011, 669 p., pp.56-9.

[10] Ibid, p.111.

[11] Cf. Introduction.

[12] Ryo Kohsaka, Mi Sun Park et Yuta Uchiyama, « Beekeeping and honey production in Japan and South Korea: past and present », Journal of Ethnic Foods, juin 2017, vol. 4, no 2, p. 72‑79, p.74.

[13] Ibid., p. 74.

[14] Pierre-François Souyri, Nouvelle histoire du Japon, Paris, Perrin, 2010, 627 p.

[15] Penelope Francks, Japan and the great divergence: a short guide, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, 123 p, p. 42.

[16] Ibid., Chap. 10.

[17] Federico Marcon, The knowledge of nature and the nature of knowledge in early modern Japan, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 2015, 415 p., p. 19.

[18] Ibid., pp.4-5.

[19] Ibid., p.5.

[20] Conrad D. Totman, Japan: an environmental history, New paperback edition., London New York, I.B. Tauris, 2016, 1114 p. (e-book), pp. 546-8.

[21] F. Marcon, The knowledge of nature and the nature of knowledge in early modern Japan, op. cit., p. 73.

[22] Kaibara Ekken (1630-1714), The pharmacopeia of Japan (Yamato honzō), volume 14, 1709, Digital collections of the Diet National Library, ID000007326105, p. 16.

Apis cerena in the Japanese context

Apis cerena is a bee species present all across East Asia and parts of South-East Asia, from Siberia to the Philippines and in most territories in between. The climatic range of such a large repartition area is bound to be diverse as well. It testifies the versatility of the species and their capacity of adaptation to a rather wide range of environmental contexts[9]. A. cerana is a social species as well, dwelling also in cavities hidden from potential predators and stores honey as well, like its Western counterpart. The difference is to be found in the size of the hives and of the individuals: the colonies are smaller in number of workers and individually smaller in size compared to A. mellifera. The quantity of honey stored by A. cerana is comparatively smaller too and might be explained by the size of the colony and the nutritive needs of the bees themselves. The Japanese bee standard colony counts generally 5’000 to 7’000 individuals compared to up to 20’000 insects for A. mellifera[10]. Inside the hive, the number of rows vary between 8 and 10 compared to the 12 rows and more for western bees.

Another key difference between A. mellifera and A. cerana is their defense method against giant hornets, called hyperthermia. When a giant hornet tries to penetrate a colony, the worker bees from A. cerana gather into a ball around the hornet and increase the temperature at the center of the ball up to 47 degrees. This way, the bees kill the hornet by heating it up beyond a point where its vital functions aren’t able to keep up. The defense mechanism unique to A. cerana has never been observed in Apis mellifera’s behavior, which has become a critical handicap for the European colonies. Confronted for the first time to a predator they never met, western honeybees are defenseless against the Asian hornet. Hence, since its presence has first been noticed during the 2000’s the Asian hornet became a significant threat for the survival of A. mellifera’s apiaries[11]. It adds to other menaces such pesticides, the CCD (Colony Collapse Disorder) and parasites such the acarian Varroa destructor.

Based on historical evidence, the first mention of beekeeping was made in one of the oldest written sources of Japanese history, the Nihonshoki or “the Chronicles of Japan”, which makes a mention of honey as a gift to the Emperor. We can observe from that anecdote that honey was considered as a precious item, luxurious enough to be made an imperial gift. Honey was then seen as a medicinal item too, due to the antiseptic properties of honey and its nutritive values[12]. Throughout Japanese history, others mention beekeeping during the antique and medieval periods. It seems that during these periods, the practice of beekeeping was not very widespread and was confined to precise corners.

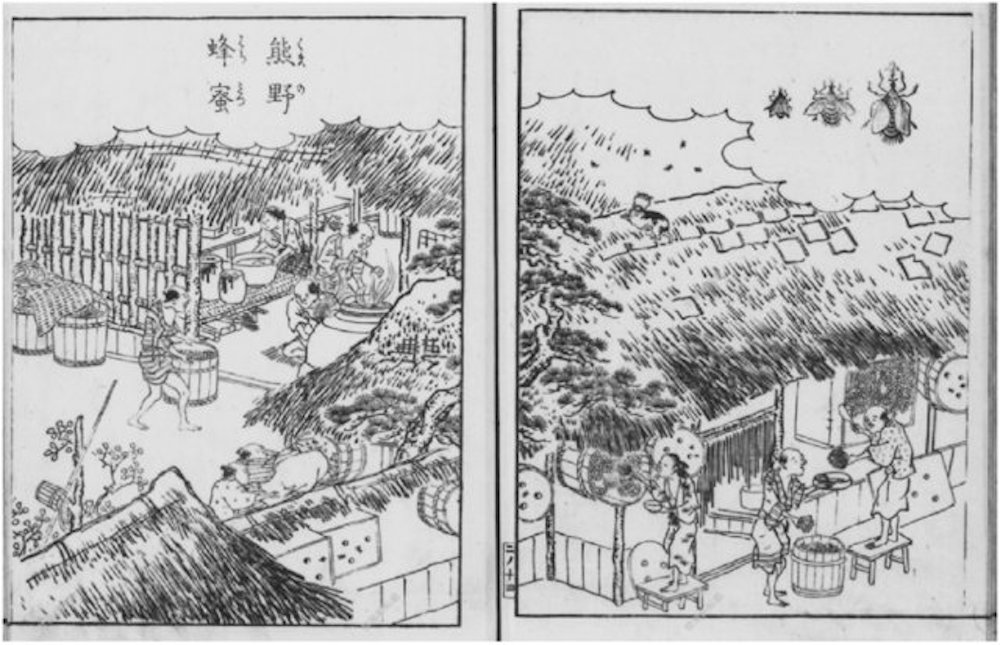

Beekeeping, as a craft and an art, began to spread on a larger quantitative level during the Edo period (1600-1868)[13]. The three main regions where apiculture had the strongest hold were the island of Tsushima, the Kumano plain and the central part of the Japanese Alps. The reason behind the augmentation of the production of honey and related products was mainly geopolitical. The archipelago lived a long period of peace during the 268 years of the Tokugawa regime. The founder of the shogunate or bakufu was the third of the major unifiers of Japan (including Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582) and Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598)) to put progressively the different feudal domains of Japan under a same political banner, consequently ending a century old period of conflict, the Sengoku period (sengoku jidai (1477-1573))[14].

From an economic standpoint, the return of peace allowed a significant stability ideal for trade and the reestablishment of internal commercial circuits by land or sea. Globally, the trends that were observed during the Sengoku period pursued and were even amplified during the Edo period[15]. The creation of castle towns (jōka-machi) and major ports, added to their subsequent growth allowed the emergence of a noticeable urban population, possessing their own culture where the roots of a consumption society could be found. The urbanites were mostly composed of warriors (bushi), craftspeople and merchants (chōnin) and pariahs who were a marginalized social group in the urban society (hinin). The merchant class in the urban areas of Japan, aided by local domanial lords (daimyō) created the bases for a market economy and laid the foundation for proto-industrialization[16].

In the middle of this global panorama of economic prosperity and political stability, the products derived from honeybees shifted progressively from a purely religious and medicinal function to a new status, it seems, of commodity. As Federico Marcon noted in his book about honzōgaku or the study of pharmacopeia, the Edo period experienced a progressive desacralization of nature as a physical reality outside of mankind[17]. The reason behind what might look like a contradictory reality was the increasing penetration of human activities in the realm of spirits and deities, the mountain or yama opposed to the village or the human realm (sato)[18]. This phenomenon was driven by the needs of a growing population and a change of lifestyle among the population[19]. At the same time, we can note a shift from extensive agriculture to intensive agriculture, mainly fueled by the diminished mobility of agricultural populations and the lack of newly available space for crops[20].

These tendencies described above can be found for the case of honeybees as well. In 1705 by Kaibara Ekken, the bees were distinguished in three categories in the Yamato honzō or the “pharmacopeia of Yamato [Japan]”, based on their environment: the plain bee (nobachi), the house bee (iebachi) and the mountain bee (yamabachi). The status of this book is important because it represented the first book to describe the native fauna and flora of the archipelago in an encyclopedic fashion[21]. The three sorts of bees weren’t assimilated to biological reality but mostly motivated by practical reasons. The three sorts of bees could have their honey harvested and needed specific methods. Kaibara wrote for instance: “there are numerous kinds of bees: the bees of Shitsuko, the ground bees, the honeybees, the giant golden bees, the carpenter bees, the mountain bees and the deer bees.”[22]

Another key difference between A. mellifera and A. cerana is their defense method against giant hornets, called hyperthermia. When a giant hornet tries to penetrate a colony, the worker bees from A. cerana gather into a ball around the hornet and increase the temperature at the center of the ball up to 47 degrees. This way, the bees kill the hornet by heating it up beyond a point where its vital functions aren’t able to keep up. The defense mechanism unique to A. cerana has never been observed in Apis mellifera’s behavior, which has become a critical handicap for the European colonies. Confronted for the first time to a predator they never met, western honeybees are defenseless against the Asian hornet. Hence, since its presence has first been noticed during the 2000’s the Asian hornet became a significant threat for the survival of A. mellifera’s apiaries[11]. It adds to other menaces such pesticides, the CCD (Colony Collapse Disorder) and parasites such the acarian Varroa destructor.

Based on historical evidence, the first mention of beekeeping was made in one of the oldest written sources of Japanese history, the Nihonshoki or “the Chronicles of Japan”, which makes a mention of honey as a gift to the Emperor. We can observe from that anecdote that honey was considered as a precious item, luxurious enough to be made an imperial gift. Honey was then seen as a medicinal item too, due to the antiseptic properties of honey and its nutritive values[12]. Throughout Japanese history, others mention beekeeping during the antique and medieval periods. It seems that during these periods, the practice of beekeeping was not very widespread and was confined to precise corners.

Beekeeping, as a craft and an art, began to spread on a larger quantitative level during the Edo period (1600-1868)[13]. The three main regions where apiculture had the strongest hold were the island of Tsushima, the Kumano plain and the central part of the Japanese Alps. The reason behind the augmentation of the production of honey and related products was mainly geopolitical. The archipelago lived a long period of peace during the 268 years of the Tokugawa regime. The founder of the shogunate or bakufu was the third of the major unifiers of Japan (including Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582) and Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598)) to put progressively the different feudal domains of Japan under a same political banner, consequently ending a century old period of conflict, the Sengoku period (sengoku jidai (1477-1573))[14].

From an economic standpoint, the return of peace allowed a significant stability ideal for trade and the reestablishment of internal commercial circuits by land or sea. Globally, the trends that were observed during the Sengoku period pursued and were even amplified during the Edo period[15]. The creation of castle towns (jōka-machi) and major ports, added to their subsequent growth allowed the emergence of a noticeable urban population, possessing their own culture where the roots of a consumption society could be found. The urbanites were mostly composed of warriors (bushi), craftspeople and merchants (chōnin) and pariahs who were a marginalized social group in the urban society (hinin). The merchant class in the urban areas of Japan, aided by local domanial lords (daimyō) created the bases for a market economy and laid the foundation for proto-industrialization[16].

In the middle of this global panorama of economic prosperity and political stability, the products derived from honeybees shifted progressively from a purely religious and medicinal function to a new status, it seems, of commodity. As Federico Marcon noted in his book about honzōgaku or the study of pharmacopeia, the Edo period experienced a progressive desacralization of nature as a physical reality outside of mankind[17]. The reason behind what might look like a contradictory reality was the increasing penetration of human activities in the realm of spirits and deities, the mountain or yama opposed to the village or the human realm (sato)[18]. This phenomenon was driven by the needs of a growing population and a change of lifestyle among the population[19]. At the same time, we can note a shift from extensive agriculture to intensive agriculture, mainly fueled by the diminished mobility of agricultural populations and the lack of newly available space for crops[20].

These tendencies described above can be found for the case of honeybees as well. In 1705 by Kaibara Ekken, the bees were distinguished in three categories in the Yamato honzō or the “pharmacopeia of Yamato [Japan]”, based on their environment: the plain bee (nobachi), the house bee (iebachi) and the mountain bee (yamabachi). The status of this book is important because it represented the first book to describe the native fauna and flora of the archipelago in an encyclopedic fashion[21]. The three sorts of bees weren’t assimilated to biological reality but mostly motivated by practical reasons. The three sorts of bees could have their honey harvested and needed specific methods. Kaibara wrote for instance: “there are numerous kinds of bees: the bees of Shitsuko, the ground bees, the honeybees, the giant golden bees, the carpenter bees, the mountain bees and the deer bees.”[22]

[Picture] Print of the industry of Japanese beekeeping, Nihon Sankai Meibutsu Zue,. Kochi Castle Museum of History (Kōchi kenritsu Kōchijō rekishi hakubutsukan 高知県立高知城歴史博物館), s.d., Source: Ryo Kohsaka et alii, Beekeeping and honey production in Japan and South Korea: Past and Present, 2017, View source, consulted on 05.02.2022.

[23] Shinkai Rika, Maximilian Spiegelberg, Christoph Rupprecht, Sawazaki Kenichi, Traditional Japanese Honeybee Beekeeping in Kozagawa, Wakayama, 2019, 30 min., View source >>, consulted on 06.02.2022.

[24] E. Crane, The world history of beekeeping and honey hunting, op. cit., pp. 272-4.

[25] Unknown, “The History of Beekeeping in Japan” (Nihon no yōhō no rekishi), 2022, Japanese Beekeeping Association (Nihon yōhō kyokkai), View source, consulted on 06.02.2022.

[26] Guillaume Carnino, Liliane Hilaire-Pérez et Aleksandra Kobiljski (eds.), Histoire des techniques : mondes, sociétés, cultures XVIe-XVIIIe siècle, 1re édition., Paris, PUF, 2016., p. 621.

From the technical point of view, each region had their own beekeeping tradition, even though the species was overall A. cerana had a specific husbandry method, varying because of the local conditions of the beehives. In the Kumano plain, nowadays partly lying in the Wakayama prefecture, honeybees were kept in empty pine tree trunks where combs were suspended by a thin iron bar. The method, still in use today, is quite adapted to forested environments where wood is readily available. Moreover, the subtropical climate of the plain, more broadly of the Kii peninsula, allows the hives to be protected from heavy rainfalls and the humidity of the region[23]. Let’s consider another context: in the domestic context, apiaries adapt to the local economic realities. Near settlements, the agricultural surroundings make the use of straw as a prime material more affordable[24]. Thus, it was possible to see, and still is, box shaped apiaries made of rice straw, tied to the walls of rural houses in Japan. Otherwise, the straw-made beehives can take the shape of a bell basket, where bees can find shelter.

The latter half of the Edo period saw the increase in the literature dedicated to bees and the best techniques to sustain a viable colony in order to yield honey regularly[25]. The infiltration of the Western knowledge in general, through the Dutch by the port city of Nagasaki, inspired partly a literature mostly on agronomical matters with the objective to increase the productivity of the crops or the livestock[26]. Among those books we may find for instance the proto-entomological “Notes of a thousand insects” (Chichō sen) by Kurimoto Tanshū.

The latter half of the Edo period saw the increase in the literature dedicated to bees and the best techniques to sustain a viable colony in order to yield honey regularly[25]. The infiltration of the Western knowledge in general, through the Dutch by the port city of Nagasaki, inspired partly a literature mostly on agronomical matters with the objective to increase the productivity of the crops or the livestock[26]. Among those books we may find for instance the proto-entomological “Notes of a thousand insects” (Chichō sen) by Kurimoto Tanshū.

[27] Kaise Shūichi, The beginning of Japanese Western Beekeeping History (Nihon no seiyō mitsubachi shi no hajimari), 2020, View source, consulted on 06.02.2022.

[28] Ibid, Ōkubo Toshimichi, Tanaka Masao and Takeda Shōji (Ōkubo Toshimichi to Tanaka Masao to Takeda Shōji), 2020, View source, consulted on 07.02.2022.

[29] Tokyo National Museum, 2. The Vienna World’s Fair: The Origin of the Modern Museum (Uīn yorozukoku hakkeikai kindai habutsukan haten no genryū), 2022, View source, consulted on 07.02.2022.

[30] Coll., Vienna’s World’s Fair 1873 (Exposition Universelle de Vienne 1873), 1873, Paris, worldsfair.info, p. 248, View source, consulted on 30.01.2022

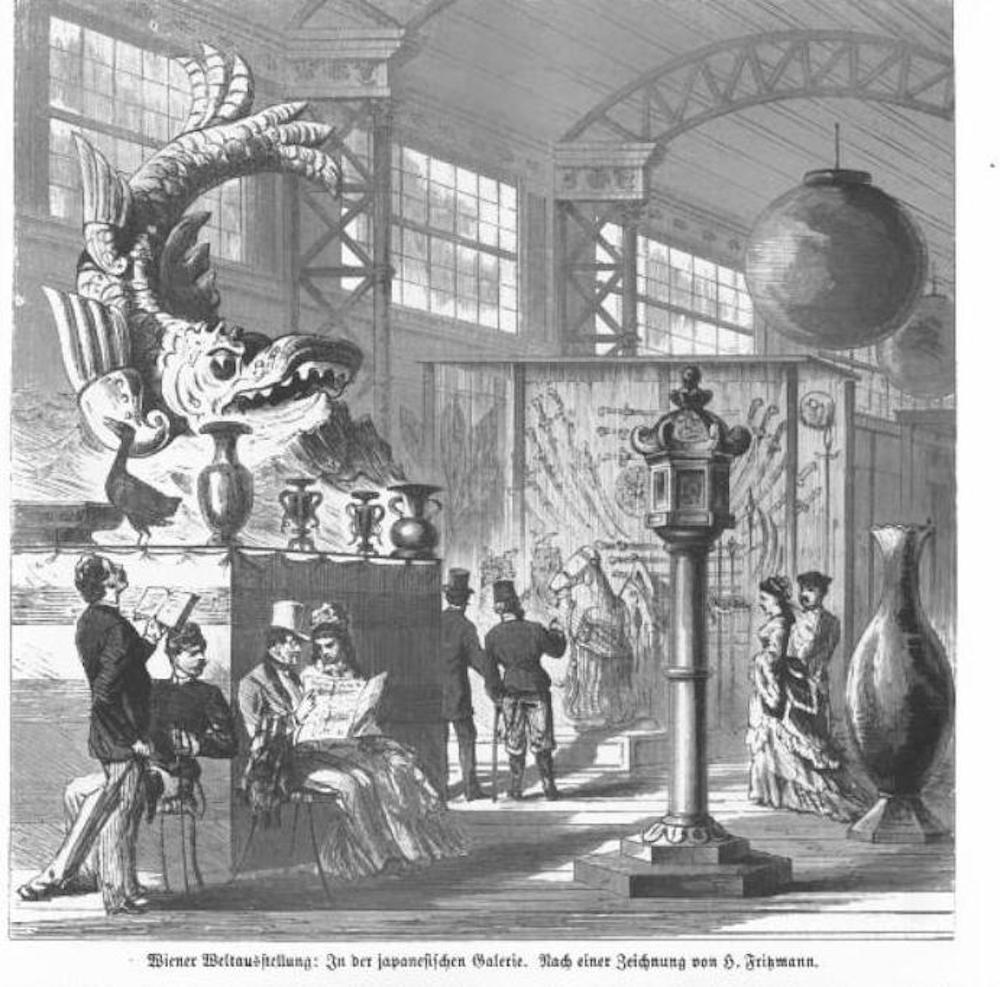

[Picture] Vienna World’s Fair: in the Japanese Galerie. After a drawing from B. Frihmann. 1873. Source: wikimedia commons.com.

Welcoming Apis mellifera

The arrival of Apis mellifera is characterized firstly by a period of individual endeavors and trials to introduce Western honeybees in Japan. This pioneering phase began right after the Meiji Restoration of 1868, and concentrated in different areas of Japan, mainly in the prefectures of Wakayama, Nagano and Tokyo proper, we have trace of experimentation of Western honeybees even on the Ogasawara Archipelago[27]. As the Japanese apicultural circles were discovering the technology developed by Westerners for beekeeping, the Western public could discover how beekeeping was done on the other end of the Eurasian continent during the Universal Exhibition of Vienna in 1873-4. The exhibition is the occasion for the newly established Japanese government who took the occasion to study closely the latest advancements of Western industries, while demonstrating what was the local craft in each province in two specimens gathered first at the future University of Tokyo before being sent to Vienna[28]. To the eyes of the government officials, in particular Ōkuma Shigenobu (1838-1922) and Satō Tsunetami (1822-1902), the World’s Fair of 1872-3 was taken seriously and went beyond an operation of cultural diplomacy[29]. One of the commentaries about the Japanese garden of the pavilion gave a detailed description of it: «In the park located on the right of the Exhibition, not far from the pavilion of the Viceroy of Egypt, is the Japanese garden, with its houses, its small river in miniature, on which is thrown a tiny bridge in bamboo.

The entrance is on the side of the flower exhibition: two poles, supporting long strips of painted paper, invite you to enter this section where the strange is mixed with the fantastic.

[...]

The paths are lined with small stones of different colors; trees which in our climate are renowned for their size, such as the oak and the fir, are represented by dwarfs of an original effect. It is a special taste of the Japanese to have completely stunted trees in their gardens. They have procedures to restrict the growth of trees and force them to remain small. Their joy is at its peak when they can manage to shrink an oak tree to the height of a rose bush.

[...]

This fish represents a carp of remarkable muscular strength, which allows it to swim up streams and even waterfalls. This paper fish is placed on the roof of the houses, on the occasion of a great festival which falls on the fifth day of the fifth month, the festival of the boys. It is the symbol of strength.

[...]

The Emperor and Empress of Austria have deigned to inaugurate, by their presence, this Japanese garden where the flora bends to the most whimsical whims, and the public rushes every day to admire these dwarf trees, which are always a subject of astonishment, as well as the Japanese house with its paper hangings, its paper blinds and its carpets, always of paper, without paper of the lanterns whose transparency allows to admire its paintings varnished with an eminently Japanese art.” [30]

The entrance is on the side of the flower exhibition: two poles, supporting long strips of painted paper, invite you to enter this section where the strange is mixed with the fantastic.

[...]

The paths are lined with small stones of different colors; trees which in our climate are renowned for their size, such as the oak and the fir, are represented by dwarfs of an original effect. It is a special taste of the Japanese to have completely stunted trees in their gardens. They have procedures to restrict the growth of trees and force them to remain small. Their joy is at its peak when they can manage to shrink an oak tree to the height of a rose bush.

[...]

This fish represents a carp of remarkable muscular strength, which allows it to swim up streams and even waterfalls. This paper fish is placed on the roof of the houses, on the occasion of a great festival which falls on the fifth day of the fifth month, the festival of the boys. It is the symbol of strength.

[...]

The Emperor and Empress of Austria have deigned to inaugurate, by their presence, this Japanese garden where the flora bends to the most whimsical whims, and the public rushes every day to admire these dwarf trees, which are always a subject of astonishment, as well as the Japanese house with its paper hangings, its paper blinds and its carpets, always of paper, without paper of the lanterns whose transparency allows to admire its paintings varnished with an eminently Japanese art.” [30]

[31] Coll., Vienna’s World’s Fair 1873 (Exposition Universelle de Vienne 1873), 1873, Paris, worldsfair.info, p. 248, View source, consulted on 30.01.2022

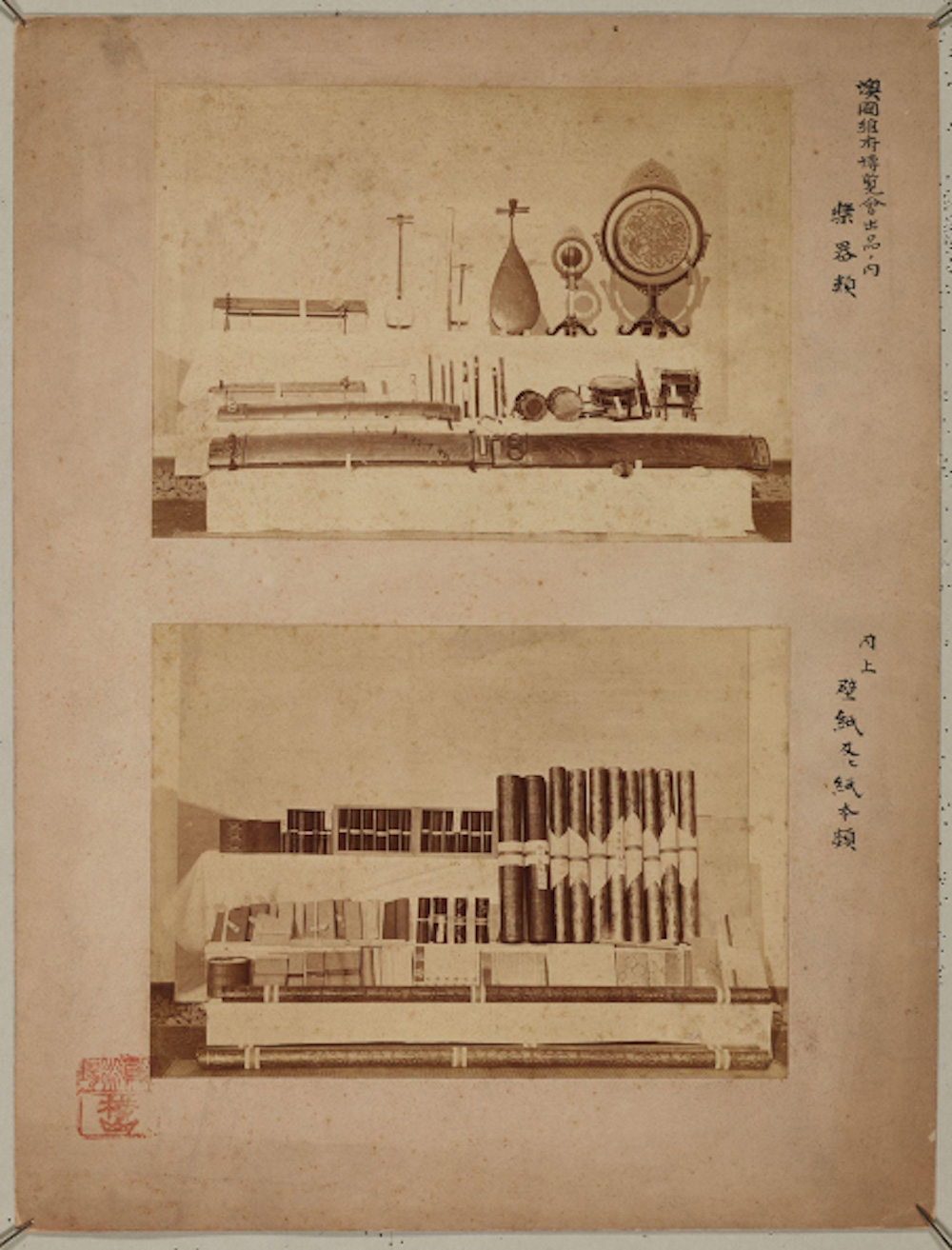

[Picture] Couple of photographs showing the items exposed in the Japanese pavilion, 1872, Photographs of Works Shown at First Kanko Bijutsukai Exhibition: Painting and Sculpture, dated 1880. View source, consulted on 30.01.2022.

We can consider it as an operation of scientific and industrial intelligence. The personnel employed at the Japanese pavilion counted 72 persons, including 41 officials, 6 interpreters and 25 craftsmen among whom were beekeepers[31]. Among the shown objects were a replica of the Buddha of Kamakura or objects purchased in Hokkaidō and the Ryūkyū Islands. The impression emanating from the pictorial documents of the pavilion's inside was the condensation of the most notable sights of the archipelago in a small space, highlighting what the Japanese identity was based on, in the eyes of officials.

[32] Ryo Kohsaka, Mi Sun Park et Yuta Uchiyama, « Beekeeping and honey production in Japan and South Korea: past and present », Journal of Ethnic Foods, juin 2017, vol. 4, no 2, p. 72‑79, p.74.

[33] Gene Kritsky, The quest for the perfect hive: a history of innovation in bee culture, New York, Oxford University Press, 2010, 198 p.: Chapters 9 to 12 give us a perfect example of the accumulations of changes that led ultimately to the one used nowadays in Japan.

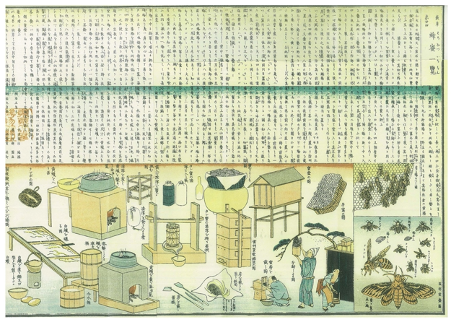

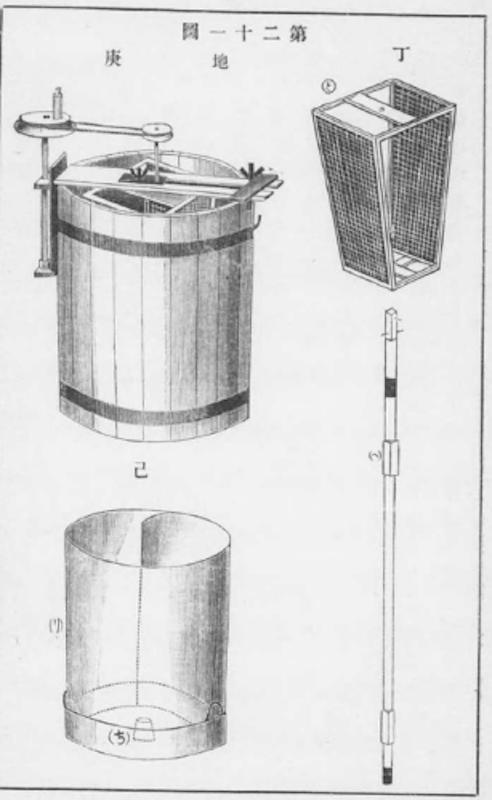

[Picture] Yōhō Ikken or A Picture of Beekeeping, Tanba Yoshiharu, Mizonokuchi Gekkō (text; drawing), 1872, View source

One document presented in what consisted of Japanese beekeeping traditions, “A Picture of Beekeeping” (Yōhō Ikken). The picture illustrates in an ukiyo-e style painting the principal tools of beekeeping, the Asian bees, the nefarious species and method employed to extract honey and wax (Pic. 2). Such a snapshot is particularly precious for the chronology of the partial shift from one type of practice to another and how both of Western and local beekeeping styles would interact[32]. The illustration shows that beehives used in the Japanese style context were quite resemblant to what we could find in the late Meiji era, about 30 years later. One explanation could be that the technological inspiration of Western beehives inspired from the Langstroth model was already in vigor or that one strain of apiary would look similar to what we find a few decades later[33]. This document presents us a snapshot of beekeeping during this pivotal moment where the influence of the Edo period was still vivid. The text above the illustrations explains where to find wild bees and how to capture them with a special basket. Later, the explanation goes on to differentiate the different species of bees and their respective location, like the “Bear honeybees” or the “Mountain honeybees” which are called in Japanese Kumamitsubachi and Yamamitsubachi found in the province of Izumo (present Shimane prefecture). This type of bees is reputed to be very hard to raise, identified nowadays as Carpenter bees (Xylocopa family). The writer warns the reader that “Red bees” (akabachi), or in latin Vespa simillima xanthoptera could be a danger for the Bear bees because as hornets, they could possibly enter the nest and decimate the colony. The Yōhō Ikken continues its detailed summary of Japanese beekeeping by process of swarming and the method to harvest honey and their different types. “The combs will have to be cut with tools if it cannot be done with hands. The combs are placed after that in a bamboo staff sealed with a piece of fabric or a sift. The honey will drip in the bottle by itself. The honey would have a yellow-brown color and would look like candy, this honey is called the Taremitsu or “gravy-honey”. It is heavier and darker than the honey made in villages. The rest will be put in a cloth bag and placed in a wood press like indicated in the scheme, producing honey again. But if the honey is mixed to larvaes and combs, it is considered of inferior quality called Shiborimitsu or “pressed honey”."

[34] Unknown, 3. The Introduction of the Western Bee- the Embryonic Period (Yōbachi dōnyū- shūhō jidai), 2021, URL: http://www.beekeeping.or.jp/beekeeping/history/japan, consulted on the 07.02.2022.

[35] Yoshida Kōzō, The New Treaty of Experimental Beekeeping (Jikken Yōhō Shinsho), Sugimaru Kankō (ed.), 1908, ID-064788-000-4, Preface.

[36] Penelope Francks, Rural economic development in Japan: from the nineteenth century to the Pacific War, London ; New York, Routledge, 2006, 312 p., p. 146.

[37] The book being published in 1908, it represented a resume of more than 30 years of research then institutionalized around experimental stations.

[38] Kaise Shūichi, Japan’s very first Western Honeybee Breeding -part 1 (Nihon saisho no seiyō mitsubachi shiiku – sono 1), 2020, View source, consulted on 08.02.2022.

[39] Yoshida Kōzō, The New Treaty of Experimental Beekeeping (Jikken Yōhō Shinsho), Sugimaru Kankō (ed.), 1908, ID-064788-000-4, p. 16.

[40] Ibid, p. 33.

[41] Ibid, p. 19.

[42] Ibid, p. 19.

[43] Ibid, p. 18.

[44] M. Tanimoto (ed.), The role of tradition in Japan’s industrialization, op. cit., chapter 4.

[45] Tessa Morris-Suzuki, The technological transformation of Japan: from the seventeenth to the twenty-first century, Cambridge ; New York, Cambridge University Press, 1994, 304 p., pp. 36-43.

[46] Ian Jared Miller, Julia Adeney Thomas et Brett L. Walker (eds.), Japan at nature’s edge: the environmental context of a global power, Honolulu, University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2013, 322 p., pp. 79; 176.

[47] Julia Adeney Thomas, Reconfiguring modernity: concepts of nature in Japanese political ideology, Berkeley, Calif, University of California Press, 2001, 239 p., p. 65.

[48] Tamari Kizō, Extended Amelioration of Beekeeping (Zōho yōhō kairyō setsu), Yurindo publishing, 1913, ID 24-689, National Diet Library, Preface.

[49] Ibid., p. 14.

[50] Based on the analyze of the books of Yoshida and Tamari, added to the fact that the Suwa district is situated in the same prefecture.

[51] Ueda City Multimedia Information Center, Miyoshi Yonekuma, Modern Japan’s Pioneer of Sericulture/Agronomy Professor (Miyoshi Yonekuma, kindai nihon no yōsan no senkusha/ nōgyō hakase), View source, consulted on 08.02.2022.

[Picture] : Figure and plan of a honey centrifuge, including components, Tamari Kizō, op. cit., p. 89.

In the credits of the text lies an important name, because the document was sold at the Watanabe Apiaries (Watanabe Yōhōba), whose owner was Watanabe Kōichi and to which this reproduction above seems to have belonged. The Watanabe family likely occupied a major role in the arrival and consolidation of the A. mellifera in Japan among others[34]. One of his relatives, Watanabe Kiyozato, was a teacher in the Prefectural Agronomical School of Nagano, Chīsanogata district[35]. The school was one of the first experimental stations established by the central and the prefectural governments for agronomical research, where beekeeping occupied an important role in the research[36]. Even though little is known about Yoshida Kōzō, the author of the book “The New Treaty of Experimental Beekeeping” (Jikken Yōhō Shinsho) summarizes the advancements made by the Mt. Nikkō Agronomic Experiment Station in Gifu prefecture. The interesting characteristic of the document is to compile the results of four decades of research about the implantation of Apis mellifera in Japan[37]. The research for the experiments began in 1877, with the first imports of Western honeybee hives from the United States and Europe, based on the History of Great Japan’s Agronomy[38]. The main inquiries were to find the best suited places for beekeeping with A. mellifera in Japan, to select the best-suited varieties, to develop the optimal form of apiary for local needs and to study the potential honey yields and eventual incomes made by doing so. “From a certain fashion, the life cycle of bees is formed of three seasons: spring, summer and autumn. The most adequate place is a territory in high altitude where flowers bloom steadily and the weather relatively fresh. Moreover, the mountain chains are continuous in our country. Most of the time, their extent goes until the seashore, without the exception of places like Tanba, Yamashiro, Yamato, Iga, Kai, Ōmi, Mino, Hida, Shinano, Ueno, Shitano and Iwashiro, cornered on four sides by mountains. The inland provinces and the highlands, with marshes and lakes in between, with fresh summers as mentioned above, where flagrant flowers disperse their sweet perfume until the end of autumn are undeniably the bees’ favorite biotop.” [39]

Based on the work of Yoshida, the best sites in Japan are located in mountainous or hilly areas in valleys, where the best conditions for beekeeping can be found. The concerned provinces are: Tanba, Yamashiro, Yamato, Iga, Kai, Ōmi, Mino, Hida, Shinano, Ueno, Shitano and Iwashiro. Indeed, most of the cited provinces are landlocked provinces situated in the Japanese Alps or in the neighboring mountain chains of Kantō or Kinki regions[40]. The principal issue was to find non cultivated fields, mostly rice paddy fields, because honeybees need a great deal of vegetal diversity for a maximum pollination period, so for the production of honey too. The varieties that were finally dimmed as the finest were the Italian and Cyprian bees[41]. The reasons behind the selection of the bees were motivated by a down-to-earth approach, practical approach from the beekeepers. Bees had to be not aggressive, highly productive, easy to maintain or to manipulate and extremely docile[42]. Concerning potential yields of honey, the available surface for beekeeping was around 1’7000 square ri (=3.93 km), which represents 258’570 km2 and about two thirds of Japan’s total current surface (377’975 km2). This allows to place 850’000 apiaries in total, that could produce in average annually 2’125’000 monme or 708 T of honey every year, for the price of 4’300’000 yens of 1910 in total[43]. We have to keep in mind that these prices were hypothetical profits and the historical yields during the pre-war period.

The most interesting part of the book and the one produced during the Meiji period and later is how modernity as a notion has been introduced to the world of beekeeping. Beekeeping, for this instance, seemed to have followed the same trajectory as the silk industry. Both industries have local premodern roots and based both on the insects to produce a range of products with a large array of use[44]. Moreover, the silk and honey or beeswax industry developed during the premodern period a long and complex production process where numerous skilled workers were involved[45]. The bombyx and the bees were considered beyond their sole being but more from a practical point of view, where the economic and technological aspects mattered mostly. In a way, by reading the documents of the era, we might feel that bees and silkworms were a cog, a part of a larger system organized towards the obtention of the final products[46]. When Japan became involved further into global exchange networks, as Julia Aderney Thomas points out in her book, Nature came to be considered as a temporal phenomenon[47]. Translated into geopolitical terms, countries competed against each other for the best economic opportunities and political high ground. Japan, willingly or not, viewed itself backwards, late compared to Euro-America in various domains, but mostly in the military and industrial sectors. In order not to be reduced to a semi-colonial status, the country was bound to “catch up” by adopting the tools of Western Powers. Integrated to the agronomic sector, the silk and the honey industry underwent modernization and became objects of progress (shimpo)[48]. In other words, the premodern methods were labeled obsolete and had to be “ameliorated”. He writes: “Even though our country has a tradition of beekeeping, the yields of honey are varying in spite of this isn’t the only source of income that comes to beekeepers’ minds. Based on a survey of 1886, the number of apiaries in Tokyo, Kyūshū, Shikoku and Chūgoku - one urban prefecture and thirteen others- is 38’615 for a total honey production of 99’703 kin [1 kin = 600 g]. In 1887, the number was of 36’951 apiaries, with a price of 45 sen per kin and down to 22 sen for European and American honey. However, the techniques used in the beekeeping industry there are slightly ameliorated compared to ours. Although each country is moderately above average, these reformed techniques are fairly new; by applying those to our industry, we could surpass the United States.” [49]

Concretely, one part of the so-called amelioration process consisted in a quest for productivity and for efficiency of production methods. Another part of this search was to find the way to implement the important structural changes reformers had in mind and concretize these into the rural economy and by spreading their findings to a larger public beyond the circles of beekeepers. In certain areas, the two industries intertwined because of their common geographical delimitations. For example, Nagano prefecture was famous for both of these industries, leading to overlapping with shared personnel and education structures[50]. For example, Miyoshi Yonekuma (1860-1927) was one of the contributors of the foreword of “The Experimental Beekeeping” volume. Being the director of the Agronomical School of Chisanokado, he was considered as one of the first specialists of sericulture in Japan, after studying under famous agronomists and abroad in silk weaving centers of France and Italy[51]. The agronomic circles of Nagano being probably small helped pretty much to interconnect and create bridges between the different fields of agronomy. In fact, beekeeping was generally considered as a sub-field of the domain rather than a field in its own right.

Based on the work of Yoshida, the best sites in Japan are located in mountainous or hilly areas in valleys, where the best conditions for beekeeping can be found. The concerned provinces are: Tanba, Yamashiro, Yamato, Iga, Kai, Ōmi, Mino, Hida, Shinano, Ueno, Shitano and Iwashiro. Indeed, most of the cited provinces are landlocked provinces situated in the Japanese Alps or in the neighboring mountain chains of Kantō or Kinki regions[40]. The principal issue was to find non cultivated fields, mostly rice paddy fields, because honeybees need a great deal of vegetal diversity for a maximum pollination period, so for the production of honey too. The varieties that were finally dimmed as the finest were the Italian and Cyprian bees[41]. The reasons behind the selection of the bees were motivated by a down-to-earth approach, practical approach from the beekeepers. Bees had to be not aggressive, highly productive, easy to maintain or to manipulate and extremely docile[42]. Concerning potential yields of honey, the available surface for beekeeping was around 1’7000 square ri (=3.93 km), which represents 258’570 km2 and about two thirds of Japan’s total current surface (377’975 km2). This allows to place 850’000 apiaries in total, that could produce in average annually 2’125’000 monme or 708 T of honey every year, for the price of 4’300’000 yens of 1910 in total[43]. We have to keep in mind that these prices were hypothetical profits and the historical yields during the pre-war period.

The most interesting part of the book and the one produced during the Meiji period and later is how modernity as a notion has been introduced to the world of beekeeping. Beekeeping, for this instance, seemed to have followed the same trajectory as the silk industry. Both industries have local premodern roots and based both on the insects to produce a range of products with a large array of use[44]. Moreover, the silk and honey or beeswax industry developed during the premodern period a long and complex production process where numerous skilled workers were involved[45]. The bombyx and the bees were considered beyond their sole being but more from a practical point of view, where the economic and technological aspects mattered mostly. In a way, by reading the documents of the era, we might feel that bees and silkworms were a cog, a part of a larger system organized towards the obtention of the final products[46]. When Japan became involved further into global exchange networks, as Julia Aderney Thomas points out in her book, Nature came to be considered as a temporal phenomenon[47]. Translated into geopolitical terms, countries competed against each other for the best economic opportunities and political high ground. Japan, willingly or not, viewed itself backwards, late compared to Euro-America in various domains, but mostly in the military and industrial sectors. In order not to be reduced to a semi-colonial status, the country was bound to “catch up” by adopting the tools of Western Powers. Integrated to the agronomic sector, the silk and the honey industry underwent modernization and became objects of progress (shimpo)[48]. In other words, the premodern methods were labeled obsolete and had to be “ameliorated”. He writes: “Even though our country has a tradition of beekeeping, the yields of honey are varying in spite of this isn’t the only source of income that comes to beekeepers’ minds. Based on a survey of 1886, the number of apiaries in Tokyo, Kyūshū, Shikoku and Chūgoku - one urban prefecture and thirteen others- is 38’615 for a total honey production of 99’703 kin [1 kin = 600 g]. In 1887, the number was of 36’951 apiaries, with a price of 45 sen per kin and down to 22 sen for European and American honey. However, the techniques used in the beekeeping industry there are slightly ameliorated compared to ours. Although each country is moderately above average, these reformed techniques are fairly new; by applying those to our industry, we could surpass the United States.” [49]

Concretely, one part of the so-called amelioration process consisted in a quest for productivity and for efficiency of production methods. Another part of this search was to find the way to implement the important structural changes reformers had in mind and concretize these into the rural economy and by spreading their findings to a larger public beyond the circles of beekeepers. In certain areas, the two industries intertwined because of their common geographical delimitations. For example, Nagano prefecture was famous for both of these industries, leading to overlapping with shared personnel and education structures[50]. For example, Miyoshi Yonekuma (1860-1927) was one of the contributors of the foreword of “The Experimental Beekeeping” volume. Being the director of the Agronomical School of Chisanokado, he was considered as one of the first specialists of sericulture in Japan, after studying under famous agronomists and abroad in silk weaving centers of France and Italy[51]. The agronomic circles of Nagano being probably small helped pretty much to interconnect and create bridges between the different fields of agronomy. In fact, beekeeping was generally considered as a sub-field of the domain rather than a field in its own right.

[52] Working Team of the Memory of Professor Tamari Kizō, The Life of Professor Tamari Kizō (Tamari Kizō sensei den), 1975, University of Kagoshima/ Agronomical Department.

[53] David G. Wittner et Philip C. Brown (eds.), Science, technology, and medicine in the modern Japanese Empire, London ; New York, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016, 290 p., pp. 2-4.

[54] Tamari Kizō, op. cit., p.14

[55] Idem, pp. 15-6.

[56] Kaise Shūichi, The Western Honeybee, from Ogasawara Island to the Whole of Japan (Seiyō mitsubachi, Ogawasara tō kara Nihon zenkoku he), 2020, View source, consulted on 08.02.2022.

The author of the “Extended Amelioration of Beekeeping” (Zōho yōhō kairyō setsu), published in 1889 and being the first modern beekeeping book of Japan, Tamari Kizō (1856-1931), shares the same professional fate as Miyoshi. Born as a retainer, he did a first formation in agronomy before going to the United States, especially in Michigan, to further his education before coming back to Japan working as an agronomist in different departments of the Meiji State[52]. The pinnacle of his career was to become a parliamentary in the Chamber of Pairs, the High Chamber of the Imperial Parliament in 1922. Knowing that Tamari was formed in the United States explains well the reason why Japanese beekeeping has been heavily influenced by its American counterpart. The influence of United States’ agronomics could be felt in other areas of the agrarian sciences, since most foreign advisors in the matter came from there[53]. In this instance, the foreword of Tamari’s book is interesting to analyze from this point of view because the author placed himself as most recent chapter of a long history of beekeeping that began with Aristotle in Ancient Greece before transiting by United States, as the first colonies of Apis mellifera crossing the Pacific Ocean in 1877[54]. To further this argument, Euro-America is taken as a reference for the reformation of the Japanese beekeeping, in terms of techniques and of production aims: “Such a situation is similar to the yields of American honey production, with important profits, depends on the climate and the variety of honeybees. Moreover, the plowing of large swaths of land can enrich the zone with flowers and grass. By bringing back somehow these husbandry methods, it [wouldn’t suffice]. In the aforementioned country, the annual yield per colony is 100 kin, while the colonies kept with the traditional methods don't go above a meager 10 kin.” [55]

Along with the experimentations of Tamari, joined by Aoyanagi Kōjirō (1868-?), successful transplantation of Apis mellifera hives from Italy, Cyprus and the United States have been done mainly in two extra areas of Japan outside the prefectures of Nagano and Gifu: the capital itself and the Wakayama prefecture. Tokyo was the point of arrival of Western honeybees on mainland Japan a first time in 1877 in the district of Shinjuku and in a second phase in 1894-5 with a second and more massive introduction from the Bōnin Archipelago in Shizuoka prefecture, after near twenty of successful acclimatation of bees on the Ogasawara Islands[56].

Along with the experimentations of Tamari, joined by Aoyanagi Kōjirō (1868-?), successful transplantation of Apis mellifera hives from Italy, Cyprus and the United States have been done mainly in two extra areas of Japan outside the prefectures of Nagano and Gifu: the capital itself and the Wakayama prefecture. Tokyo was the point of arrival of Western honeybees on mainland Japan a first time in 1877 in the district of Shinjuku and in a second phase in 1894-5 with a second and more massive introduction from the Bōnin Archipelago in Shizuoka prefecture, after near twenty of successful acclimatation of bees on the Ogasawara Islands[56].

[57] On Japan Search, a research with the keyword “beekeeping”/”yōhō 養蜂” between 1900 and 1920, we can count beyond 40 handbooks dedicated to beekeeping.

[Picture] Beekeeping in the dunes belt, Tottori city (Sakkyūtai no yōhō, Tottori-shi), Anonymous, 1958, Photo Archives of Japan, 00069-01949-0027,

View source

Bee keeping at the turn of the century

With the success of Tamari’s book and of the experimental stations scattered across Japan, we can notice at the turn of the 20th century a rise of interest in general for the art of beekeeping[57]. The number of books and handbooks for farmers experienced a swift increase, which testifies the interest of the public for beekeeping in Japan at this time. Beyond the editorial argument, what could explain the growing interest of the Japanese farming population during the first decades of the twentieth century, that could be considered as the spreading decades of the Western beekeeping into the archipelago as a whole and beyond?

[58] Kaise Shūichi, Aoyanagi Kōjirō, the Father of Japanese Modern Beekeeping (Nihon kindai yōhō no chichi Aoyanagi Kōjirō), 2020, View source, consulted on 08.02.2022.

[59] Japanese Beekeeping Assocation, The Development of Nomad Beekeeping (Tenchi yōhō no kaika), 2022, View source, consulted on 08.02.2022.

[60] Tamari Kizō, op. cit., p. 67.

[61] Ibid, p. 81.

[62] Ibid, p. 84.

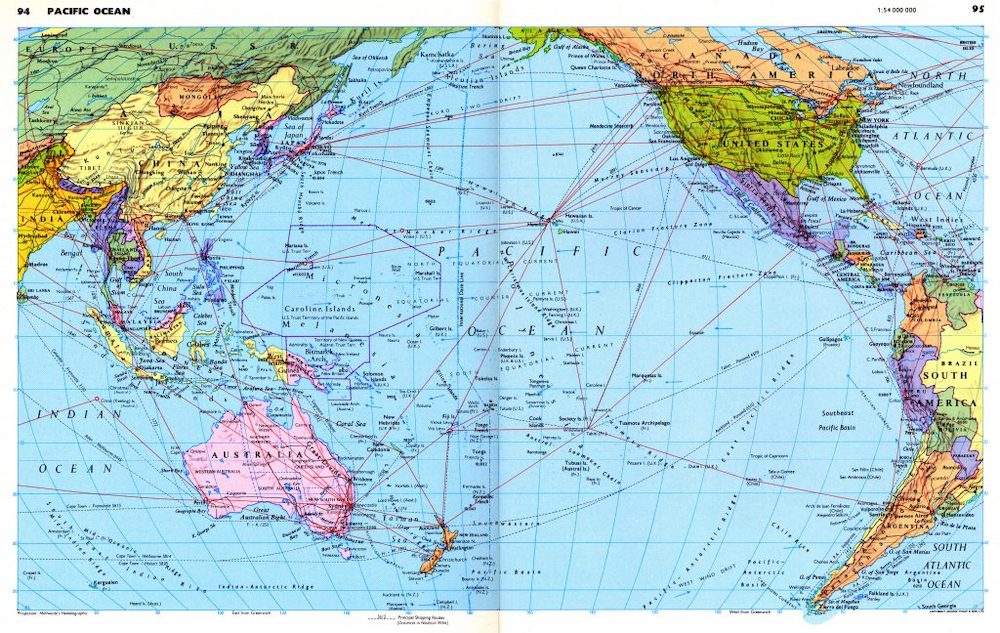

[Map] Map of Manchuria 1942, General Agricultural Association of Manchuria, uploaded by Sanmosa, View source, consulted on 05.02.2022.

One part of the answer could be the beginning of the distribution of beehives outside of experimentation stations by Aoyanagi Kōjirō starting from 1905[58]. The end of the Meiji era (1868-1912) and the beginning of the Taishō era (1912-26) announced the diffusion of Western-inspired beekeeping to the rest of the archipelago. The diffusion of reformed knowledge on beekeeping was further helped by the apparition of specialized periodicals throughout Japan on the eve of 20th century. In 1909, Watanabe started publishing for example the first beekeeping-oriented periodical with the titled “The Friends of Beekeeping” (Yōhō no dachi), followed by other periodicals on the same period, for example the “The World of Beekeeping” (Yōhōsei) along 50 other magazine titles[59]. If we dig deeper, we might understand this series of apparitions as a response to a growing demand but as also an accelerator for a domain where publications were still sparse, the public was ripe.

At the very end of his book, Tamari wrote a last chapter in the fifth edition about the situation of the honeybee market. In his opinion, the expansion of the market in the short span of 18 years is due to several factors: a better access to resources, a better protection of the apiary itself by fumigation based on more efficient fumigation products, and in addition to that the value of commodity dedicated to Japan-made honey in main urban markets, in Tokyo for example[60]. The rising demand for honey coming from all over Japan would attract more and more farming families to invest in beekeeping in hope to make interesting profits. For example, six kan of Ogasawara honey or 21 kg contained in six jars would cost in Osaka 6 yen and 50 sen or 5 kan of Nagano honey (16,75 kg)[61]. The demand for local honey is influenced by the accessibility to foreign honey as well, which are imported goods. Tamari expresses a few concerns about the competition of lesser quality foreign honey in the domestic market. One of the main leviers would be the Honey Extraction Law (Tomitsuhō), regulating the quantities and the harvest period hence controlling the potential expansion of the domestic production capacity[62].

At the very end of his book, Tamari wrote a last chapter in the fifth edition about the situation of the honeybee market. In his opinion, the expansion of the market in the short span of 18 years is due to several factors: a better access to resources, a better protection of the apiary itself by fumigation based on more efficient fumigation products, and in addition to that the value of commodity dedicated to Japan-made honey in main urban markets, in Tokyo for example[60]. The rising demand for honey coming from all over Japan would attract more and more farming families to invest in beekeeping in hope to make interesting profits. For example, six kan of Ogasawara honey or 21 kg contained in six jars would cost in Osaka 6 yen and 50 sen or 5 kan of Nagano honey (16,75 kg)[61]. The demand for local honey is influenced by the accessibility to foreign honey as well, which are imported goods. Tamari expresses a few concerns about the competition of lesser quality foreign honey in the domestic market. One of the main leviers would be the Honey Extraction Law (Tomitsuhō), regulating the quantities and the harvest period hence controlling the potential expansion of the domestic production capacity[62].

[63] Nagano Prefecture Special Products, The Current Situation of Beekeeping in the Prefecture” (Kenka ni okeru yōhō no genkyō), 1933, Shinnō Education Association edition, Mainichi Shinbun, pp. 281-302.

[64] Japanese Beekeeping Association, Wartime and Immediate Postwar Beekeeping (Senjika oyobi shūsen chokugo no yōhō), View source, consulted on the 10.02.2022.

[65] General Secretariat of Ehime Prefecture, The Statistics of Ehime Prefecture (Ehime-ken tōkeisho), General Secretariat of Ehime Prefecture, 1941, ID-0032776-001, Digital Collections of the National Diet Library, p. 21.

[66] General Secretariat of Ehime Prefecture, The Statistics of Ehime Prefecture (Ehime-ken tōkeisho), General Secretariat of Ehime Prefecture, 1941, ID-0032776-001, Digital Collections of the National Diet Library, p. 21.

[67] General Secretariat of Ehime Prefecture, The Statistics of Ehime Prefecture (Ehime-ken tōkeisho), General Secretariat of Ehime Prefecture, 1941, ID-0032776-001, Digital Collections of the National Diet Library, p. 21.

[68] C.D. Totman, Japan, op. cit., pp. 739-741.

[69] Ramon Hawley Myers et al. (eds.), The Japanese colonial empire, 1895-1945, Princeton, N.J, Princeton University Press, 1984, 540 p., pp. 38-47.

[70] William M. Tsutsui, « Landscapes in the Dark Valley: Toward an Environmental History of Wartime Japan », Environmental History, 1 avril 2003, vol. 8, no 2, p. 294‑311, p.5.

[71] Sakura Christmas, “An imperial sheep chase”, in: China Dialogue, 2017,

View source, consulted on 10.02.2022.

[72] Governor-General of Kwantung, Ground Army, Survey on the Products of Manchuria and Inner-Mongolia (Manmō sangyōshi), Minyūsha, Tokyo, 1919, ID-00533160, Digital Collections of the National Diet Library.

[73] Ibid., p. 98.

[74] James L. Huffman, Creating a public: people and press in Meiji Japan, Honolulu, Hawaii, University of Hawai’i Press, 1997, 573 p., Introduction.

[75] Anonymous, “The Promising Beekeeping Business in South Manchuria” (Zenki yūbō ni naru Nanman no yōhōjigyō), 26.11.1930, in: Manshū Nichi Nichi Shimbun, Newspaper clippings collection of the University of Kōbe.

[76] Norman Smith (ed.), Empire and the environment in the making of Manchuria, Vancouver ; Toronto, UBC Press, 2017, 299 p., p. 154.

[77] Anonymous, “The Presentation of the Five-Year Aid Plan centered around the Migrant Groups” (Imin shūdan buraku wo chūshin suru toshi kyūsai go-kanen kaikakuan wo happyō), 8.1.1936, in: Kyōgi Nippō, Newspaper clippings collection of the University of Kōbe.

[78] See supra

[79] E. Crane, The world history of beekeeping and honey hunting, op. cit., chapter 45.

[80] C.D. Totman, Japan, op. cit., p. 695.

[81] P. Francks, Rural economic development in Japan, op. cit., pp. 72; 142.

The expansion of beekeeping as an interesting source of income for farming households as well as the further transformation of honey as a consumption product, a commodity, would lead to the durable implantation of A. mellifera in the archipelago in disfavor of the local bee species, including A. cerana. At the beginning of the Shōwa era, the disparities between the two species was eloquent in certain areas of Japan. Let’s take for example the 1933 document called “The Current Situation of Beekeeping in the Prefecture” (Kenka ni okeru yōhō no genkyō), which declares that the number of beehives in prefecture of Nagano between Apis mellifera against Apis cerana is 11’850 against 3’867 colonies[63]. There is little data about the other prefectures, so it is risky to extrapolate such numbers to the rest of Japan. We might assume, however, that one of the most productive prefectures in honey could reflect an analogous disbalance with the caveat of the contrast of it. The differential might be the productive constraint due to the local beekeeping culture, pushing to maximize the produced quantity of honey.

When we move progressively to wartime Japan, the conditions of the war tended to take a toll on the beekeeping industry as a whole, shortages and military demand which used honey and wax for war goods put beehives and beekeepers under pressure[64]. The absence of men due to drafting didn’t help but the tense overall economic and material situation would have been the main break to beekeeping activities, since beekeeping was taken in charge by spouses and children in farming households. Looking at the reports of agronomic statistics of the Ehime prefecture in 1940, we could see the evolution of the honey production and the numbers of beekeeping households. Covering the first period of wartime Japan, right before the Pacific War- between 1935 and 1940, the evolution of the principal indicators is contrasted, the only indicator that decreased was the foreign bee species. The year 1939 seemed worse, where the overall indicators were lower, due probably to the drought that struck Japan and Korea. Most interesting, the trend in the five observed years was a slight fragmentation of the beehives between a greater number of beekeepers, sharing 6,794 hive boxes between 2,620 households[65]. As a supplement to the households, the ratio of boxes between native and western species shrunk first, before bouncing back in 1940 (ref. infra). In contrast to Nagano, the prefecture of Ehime bred more native bees than Apis mellifera, with a ratio of 1.6 in 1940.

The era when Western-inspired beekeeping began to take root firmly in the Japanese soil coincided as well with the formal initiation of the Japanese Empire and its intensification on the continent. Japanese encroachment in its colonies translated environmentally speaking into different forms depending on the status and the local needs of the colonizer. For example, Taiwan and Korea were designed as granaries of Japan or more largely as agriculture colonies whose goods and products were shipped to the home islands[68]. However, we need to take into account as well the chronology of the colonial control on the concerned resources and populations. There were indeed different phases in the environmental management of the colonies between 1895 and 1945, but we can break it down to three periods. The first period from 1895 to 1918 was a period of pacification for the first territories to have fallen in Japanese hands (Taiwan, Korea, Karafuto, South Manchurian and Tsingtao port), which was characterized by the construction of infrastructures ensuring the access a durable control of the acquired territories[69]. The second period from 1918 to 1937 would be a calmer phase of assimilation where the central government integrated the territories and organized in a larger framework at the scale of the realm. The invasion of Manchuria by the Kwantung Army forged the path to the third phase, during which the authorities increased the infrastructures and the heavy industries to maximize the potential of the colonial territories. These investments were a means to solidify the military potential of the continental territories in the face of the threats on the continent. The last phase ending in 1945 was the mobilization of the whole realm in total war and fueled an intensive military expansion in order to secure key-resources to the war effort[70].

Through the phenomenon of empire, the animal and vegetal collaborator species (willingly or not) accompanied their human counterparts in their movements around the globe, so did honeybees. In conquered territories, traditional forms of beekeeping existed already[71]. The Japanese presence in those influenced to an unknown extent the practices, as indicated by a survey of the products found in Manchuria made by the Kwantung Army. In 1919 was a document seeking to detail the methods and the products found in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia (Manmō). The purpose of such a publication could be interpreted as a showcase to stress the economic interest lying on the continent for Japan[72]. In this survey, beekeeping is described as marginal activity and not considered as a primordial activity[73]. The most noteworthy fact is that the Kwantung army classified this activity under animal husbandry and by mentioning such an activity, it testified the economic interest emanating from the region as a minor sector.

More interestingly, in the press, one could find some traces from the influence of Japan in local beekeeping cultures and how the Empire affected the concerned zones’ conditions. The press, in modern history, reveals itself to be the perfect proxy to observe the pace of society and to understand its preoccupations at a given epoch[74]. Obviously, we have to stay careful not to assimilate the opinion of a certain journal with the global opinion of a society on a certain subject. Concerning exporting the Japanese beekeeping products or technical knowledge outside of the home islands, newspapers gave an indirect insight of the perspective of expansion or profits given by an outside market or the trials of reforming the local beekeeping. The 26th November 1930 edition of the Manshū Nichi Nichi Shimbun “the Manchurian Daily” stressed the promising future of beekeeping in Manchuria or more globally Northern China by comparing it to Hokkaidō, the most northernmost of the home island known for its high productivity in honey and related goods. “According to a recent survey, the number of beehives in the jurisdiction of the Dalian Civil Affairs Bureau is only 385, and the yield is a meager 2,700 pounds, equivalent to about 9,000 yen. In Tianjin alone, the number of Japanese merchants importing bees during the summer season this year reached 40, and in the short period from January to September, more than 100,000 boxes were imported, which is more than 12 times as many as last year's 8,000 boxes. The Japanese bee association was formed on November 1 for the purpose of improving the bee trade, guiding and supporting the development of beekeeping in Northern China, and promoting the mutual prosperity of the bee industry”[75]. We can see in this extract how Manchuria was seen like Hokkaidō as a radiant frontier able to solve domestic problems by transforming it into a wild terra nullius[76].

In another article published in 1936 in the Kyōgi Nippō or the “Beijing Reporter”, the local government of Jiandao (Jilin Province, PRC) worked on a five-year plan to ameliorate the condition of the farmers by augmenting the productivity consisting in the introduction of new agricultural techniques. Beekeeping played in that perspective the role of the aiding factor in the augmentation of the global outputs, in other words a tool. “Beekeeping, the cultivation of fruit trees, apricots, leeks, peaches, pears, grapes, etc., and the production of linen and hemp yarn will be encouraged, with the aim of making the farmers self-sufficient”. [77]

Let’s turn now to the environmental effects of the emergence of Western-inspired beekeeping in Japan. The consequences of such a shift are not spread equally over the realm’s surface, they were mainly concentrated in Hokkaidō, Nagano, Gifu, Yamanashi, Aichi, Kyōto, Wakayama, Fukuoka and Kumamoto. These regions share the characteristics to have mountainous areas where intensive agriculture was difficult to sustain. The brunt of the ecological effects took place inland, in spaces regrouping the conditions needed for a productive beekeeping. These included a fairly fresh space, with a long flowering season with vast amounts of flowers whose diversity could sustain a solid vegetal ecosystem[78]. It was per say, not only honeybees that raised an issue but the whole system in which the colonies were embedded. The main use of honeybees, Western or Japanese, came to pollinize different crops, whether it was cereals, vegetables or in an orchard. Being linked to an intensive agricultural system as side-activity or as an auxiliary, colonies’ number was from now on dependent on the available pollen and nectar from agriculture in addition to the already present resources. The boundaries of bee’s expansion now depended on the needs of the farmers, entering into direct competition with native bee species[79].

Besides this direct ecological competition between domesticated and wild species, the overall impact of A. mellifera and A. cerana blends with the train of consequences provoked by the global changes happening to Japanese agriculture during the industrialization. The need for new farming lands and for wooden fuel led to an encroachment of the coastal and valley population into the highlands. The expansion of the human influence into highlands led to forest depletion and the fragmentation of the local species habitats, to the extent that we could observe “bald mountains' (hageyama). In his book, Conrad Totman pointed out the intensification of agriculture and its subsequent motorization, without mentioning the dependence of urban centers for their food supply, would spread progressively across the archipelago mostly in the central regions of Japan[80]. Fertilizers and intensive agriculture would lead in the long run to a deterioration of the soil.

For orchards, new varieties of crops would be introduced like apples, mostly cultivated in the Northern part of Honshū and Hokkaidō, who saw a great part of its biotas transformed into dairy farms or pasture lands. With the spread of agricultural manuals throughout Japan, introducing new types of farming techniques and new rice crops extended farther the frontier of traditional Japanese food agriculture to territories like Hokkaidō lowlands[81]. In those circumstances, honeybees became an important pillar in the crop-system to sustain its pollination while producing financially valuable goods.

When we move progressively to wartime Japan, the conditions of the war tended to take a toll on the beekeeping industry as a whole, shortages and military demand which used honey and wax for war goods put beehives and beekeepers under pressure[64]. The absence of men due to drafting didn’t help but the tense overall economic and material situation would have been the main break to beekeeping activities, since beekeeping was taken in charge by spouses and children in farming households. Looking at the reports of agronomic statistics of the Ehime prefecture in 1940, we could see the evolution of the honey production and the numbers of beekeeping households. Covering the first period of wartime Japan, right before the Pacific War- between 1935 and 1940, the evolution of the principal indicators is contrasted, the only indicator that decreased was the foreign bee species. The year 1939 seemed worse, where the overall indicators were lower, due probably to the drought that struck Japan and Korea. Most interesting, the trend in the five observed years was a slight fragmentation of the beehives between a greater number of beekeepers, sharing 6,794 hive boxes between 2,620 households[65]. As a supplement to the households, the ratio of boxes between native and western species shrunk first, before bouncing back in 1940 (ref. infra). In contrast to Nagano, the prefecture of Ehime bred more native bees than Apis mellifera, with a ratio of 1.6 in 1940.

| Year/ Number of hives | Foreign species | Native species | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1936 | 2'769 | 4’903 | 7’372 |

| 1937 | 3’138 | 4’607 | 7’745 |

| 1938 | 2’824 | 4’520 | 7’344 |

| 1939 | 2’809 | 4’392 | 7’201 |

| 1940 | 2’701 | 3’974 | 6’675 |

| 1941 | 2’621 | 4’173 | 6’794 |

Table 1: Number of apiaries found per origin between 1936-41 in Ehime Prefecture.[66]

| Year/ Hives per Household | Up to 10 | Between 10-50 | Above 50 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1936 | 2’527 | 56 | 7 | 2’590 |

| 1937 | 2’658 | 63 | 9 | 2’730 |

| 1938 | 2’596 | 50 | 6 | 2’652 |

| 1939 | 2’596 | 66 | 6 | 2’668 |

| 1940 | 2’451 | 56 | 5 | 2’506 |

| 1941 | 2’568 | 46 | 6 | 2’620 |

Table 2: Number of hives per household between 1936-41 in Ehime Prefecture. [67]

The era when Western-inspired beekeeping began to take root firmly in the Japanese soil coincided as well with the formal initiation of the Japanese Empire and its intensification on the continent. Japanese encroachment in its colonies translated environmentally speaking into different forms depending on the status and the local needs of the colonizer. For example, Taiwan and Korea were designed as granaries of Japan or more largely as agriculture colonies whose goods and products were shipped to the home islands[68]. However, we need to take into account as well the chronology of the colonial control on the concerned resources and populations. There were indeed different phases in the environmental management of the colonies between 1895 and 1945, but we can break it down to three periods. The first period from 1895 to 1918 was a period of pacification for the first territories to have fallen in Japanese hands (Taiwan, Korea, Karafuto, South Manchurian and Tsingtao port), which was characterized by the construction of infrastructures ensuring the access a durable control of the acquired territories[69]. The second period from 1918 to 1937 would be a calmer phase of assimilation where the central government integrated the territories and organized in a larger framework at the scale of the realm. The invasion of Manchuria by the Kwantung Army forged the path to the third phase, during which the authorities increased the infrastructures and the heavy industries to maximize the potential of the colonial territories. These investments were a means to solidify the military potential of the continental territories in the face of the threats on the continent. The last phase ending in 1945 was the mobilization of the whole realm in total war and fueled an intensive military expansion in order to secure key-resources to the war effort[70].

Through the phenomenon of empire, the animal and vegetal collaborator species (willingly or not) accompanied their human counterparts in their movements around the globe, so did honeybees. In conquered territories, traditional forms of beekeeping existed already[71]. The Japanese presence in those influenced to an unknown extent the practices, as indicated by a survey of the products found in Manchuria made by the Kwantung Army. In 1919 was a document seeking to detail the methods and the products found in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia (Manmō). The purpose of such a publication could be interpreted as a showcase to stress the economic interest lying on the continent for Japan[72]. In this survey, beekeeping is described as marginal activity and not considered as a primordial activity[73]. The most noteworthy fact is that the Kwantung army classified this activity under animal husbandry and by mentioning such an activity, it testified the economic interest emanating from the region as a minor sector.